Climatewire

March 19, 2018

by Niina Heikkinen

U.S. EPA boss Scott Pruitt is skilled at sticking to his talking points, particularly when it comes to climate change.

For journalists covering that issue, pushing Pruitt beyond his rhetoric has become more important as the EPA chief has become one of the Trump administration’s highest-profile officials casting doubt on mainstream climate science.

Over a year into his tenure at EPA, Pruitt has offered a rotating selection of statements on his views about climate change. Since his confirmation hearing, he has said the degree of human responsibility cannot be measured “with precision.” At least once, he has suggested climate change may even be a good thing for humans. His message has shifted somewhat depending on his audience, but his public statements regularly question the extent to which carbon dioxide emissions are affecting the planet.

Given his reliance on the same statements, researchers who track climate change communication think the media ought to change their approach when questioning the administrator.

For one thing, reporters could focus more on challenging Pruitt’s comments, rather than pressing him to articulate his beliefs on climate change, said John Cook, a research assistant professor at the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University who studies the spread of misinformation on climate change.

“What we’ve found is you can inoculate people against misinformation by explaining the techniques used to distort the facts,” Cook said.

As an example, he pointed to Pruitt’s press conference last year after President Trump announced the U.S. plan to eventually withdraw from the Paris climate agreement.

“In the press conference, [Pruitt] claims that global warming has stopped since the late 1990s. It’s very clear from the data that global warming has continued and the last few years have been the hottest on record. What he’s doing is cherry-picking, he’s not looking at the full body of evidence. He pre-selects specific data and ignores any data that contradicts that global warming isn’t happening,” he said.

Other researchers suggested different questions journalists and others could ask Pruitt to circumvent his prepared statements on climate change.

Reporters could instead focus on economics, shared values and principles of stewardship, said Max Boykoff, director of the Center for Science and Technology Policy Research at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Recently, Pruitt has spoken publicly about his belief — inspired by his religious faith — that mankind should be stewards of the land.

“If you get confrontational, you get shut down and you don’t get to ask any more questions. So it is a very intricate dance, if you will. Part of the problem is it takes sustained engagement. It takes the opportunity to ask more than just one zinger,” he said.

This mirrors the approach recently adopted by the Franciscan Action Network’s executive director, Patrick Carolan, who sat down with Pruitt for well over an hour a couple of months ago to talk about the intersection of faith and environmentalism (Climatewire, March 15).

Rather than challenging the administrator on science, reporters could ask Pruitt about climate risk management, specifically about what a climate insurance policy might look like, Dana Nuccitelli said in an email.

Nuccitelli is an environmental scientist who writes a London Guardian column, “Climate consensus — the 97%,” and blogs for Skeptical Science, a website that challenges climate skeptics’ arguments. He noted that so far EPA has only reversed steps to create such climate insurance policies within the United States.

“Pruitt has suggested we don’t know Earth’s optimal temperature and that perhaps continuing global warming might be beneficial. These positions are contradicted by a vast body of climate impacts research, but the range of possible outcomes varies from bad to catastrophic,” Nuccitelli said in an email. “While Pruitt doesn’t believe the outcome will be terribly bad or catastrophic those outcomes are nevertheless in the range of possible scenarios, based on the body of research.”

Nuccitelli warned against trying to debate climate science, because individuals who question the widely accepted research behind its causes are basing their statements in ideology and tribalism.

“Rejection of science is just a red herring to avoid discussing policy solutions. As a scientist that is a bit frustrating, but sometimes I think we just need to look past science denial and find the root of opposition of climate policies,” he said.

Cook also described Pruitt’s statements on climate change as echoing those of “run-of-the-mill denialists” on the internet. He and his colleagues found statements questioning mainstream climate science tended to fall into five main themes: Climate change isn’t real, it isn’t us, it’s not bad, there’s no hope, and general attacks on science and climate. These categories mirror the main ways those who favor climate action discuss the issue. Pruitt’s comments on climate have focused on each of these five themes over the past year, according to Cook.

“You see this exact same pattern of behavior amongst anonymous bloggers or anonymous commenters. It’s kind of striking that you have the head of the EPA regurgitating talking points you find on the comment threads on blogs,” he said. Read more …

Julia Bakker-Arkema is a fourth-year PhD candidate in the department of Chemistry & Biochemistry at the University of Colorado. Through her research at CIRES, the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, she investigates the chemistry that leads to the formation of organic aerosol particles in the atmosphere, a process that has implications for both the environment and human health. Julia also serves as the chair of the public resources committee for CU Boulder Women in Science and Engineering (WiSE), where she works to increase the visibility and retention of women in STEM fields. After graduation, she is interested in pursuing a career that bridges the gap between public knowledge and scientific understanding, and she hopes to become a lifelong advocate for science-based policy.

Julia Bakker-Arkema is a fourth-year PhD candidate in the department of Chemistry & Biochemistry at the University of Colorado. Through her research at CIRES, the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, she investigates the chemistry that leads to the formation of organic aerosol particles in the atmosphere, a process that has implications for both the environment and human health. Julia also serves as the chair of the public resources committee for CU Boulder Women in Science and Engineering (WiSE), where she works to increase the visibility and retention of women in STEM fields. After graduation, she is interested in pursuing a career that bridges the gap between public knowledge and scientific understanding, and she hopes to become a lifelong advocate for science-based policy. Kaitlin McCreery is a first year Ph.D. student in the BioFrontiers Institute and the Department of Mechanical Engineering at CU Boulder. Originally from rural North Carolina, Kaitlin obtained a Bachelor’s degree from Duke University where she studied physics and education. She is now a student in the Interdisciplinary Quantitative Biology Fellowship Program and is designing tools to study biological systems. She aims to pursue a career in research, technology, and teaching and is passionate about expanding healthcare and education to rural communities.

Kaitlin McCreery is a first year Ph.D. student in the BioFrontiers Institute and the Department of Mechanical Engineering at CU Boulder. Originally from rural North Carolina, Kaitlin obtained a Bachelor’s degree from Duke University where she studied physics and education. She is now a student in the Interdisciplinary Quantitative Biology Fellowship Program and is designing tools to study biological systems. She aims to pursue a career in research, technology, and teaching and is passionate about expanding healthcare and education to rural communities.

MeCCO Monthly Summary: General Lull in Media Reporting of Climate Change

Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO)

February 2018 Summary

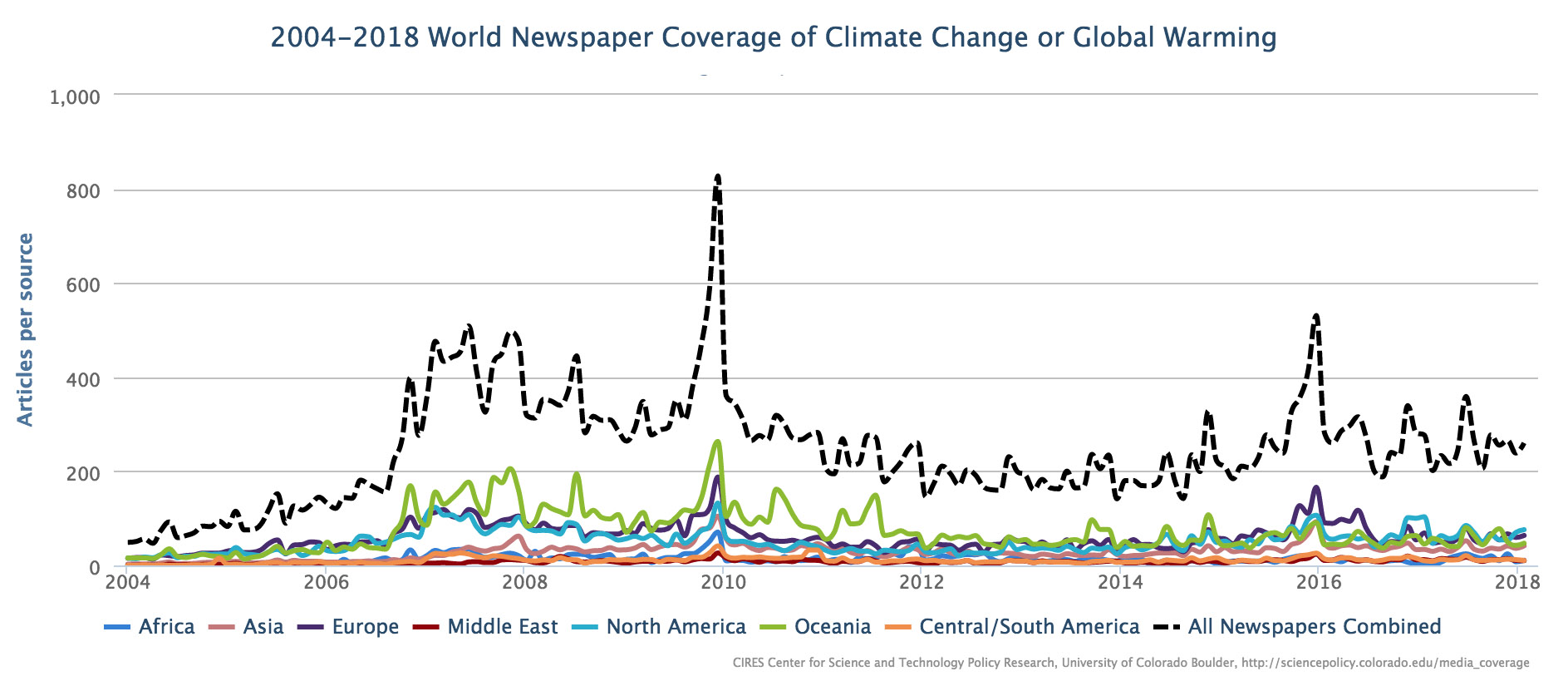

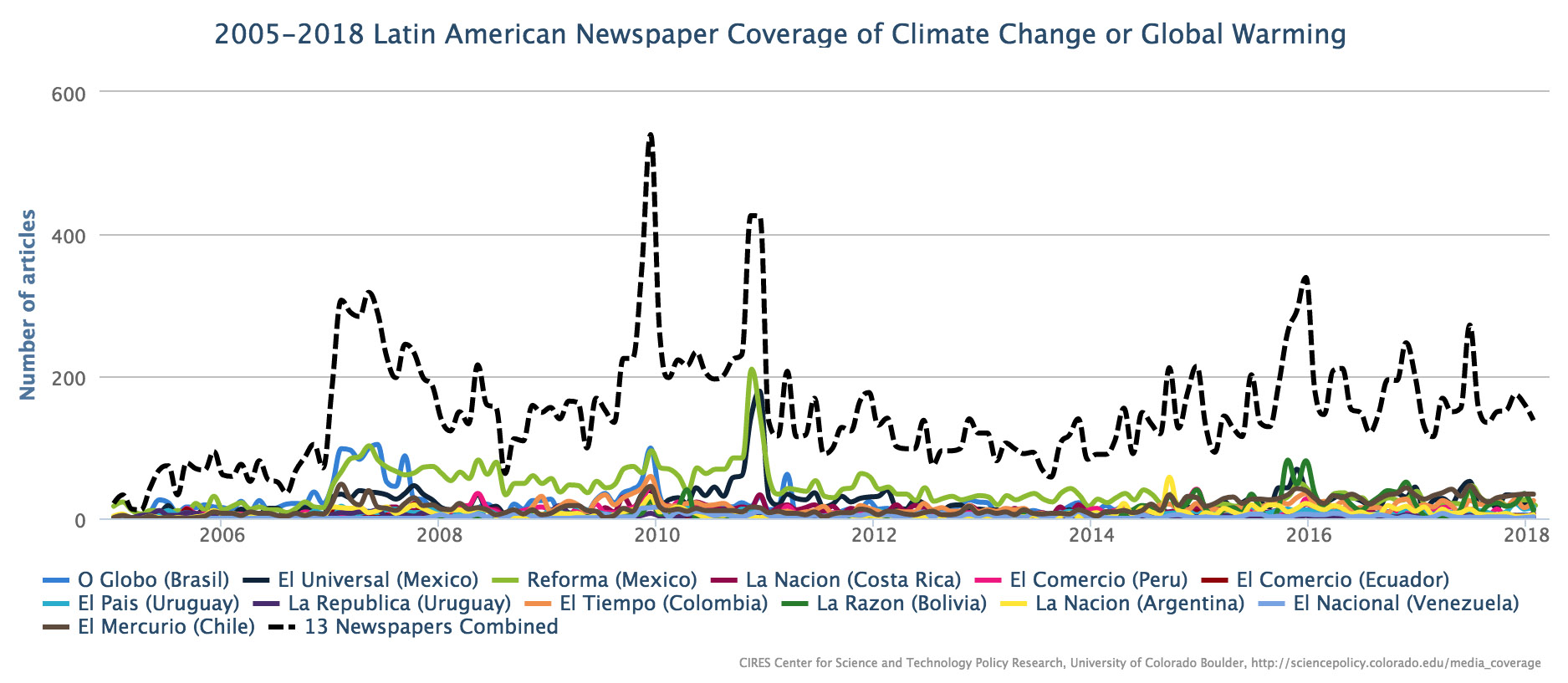

February media attention to climate change and global warming was down 23% throughout the world from the previous month of January 2018. This was the case across most regions: Asia was down 30%, Central/South America dropped 9%, Europe decreased 26%, Oceania dropped 7%, and North America was down 34%. The exceptions were Africa and in the Middle East. Global numbers were about half those (58% less) from counts a year ago (February 2017). The high levels of coverage in February 2017 were attributed to coverage of movements of the newly anointed Donald J. Trump Administration in the United States (US).

Figure 1 above shows these ebbs and flows in media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – from January 2004 through January 2018.

At the country level in February 2018, coverage also went down in most countries compared to the previous month: Germany (-5%), Canada (-13%), Australia (-13%), the United Kingdom (UK) (-17%), India (-25%), Spain (-34%), and the United States (-42%). It was just up slightly in New Zealand (+6%).

Recently, MeCCO has expanded to six world radio sources (Figure 2), with monitoring of coverage beginning in January 2000. Coverage in February 2018 compared to the previous month was also down (-62%), and coverage compared to a year ago (February 2017) was similarly reduced as well (-49%).

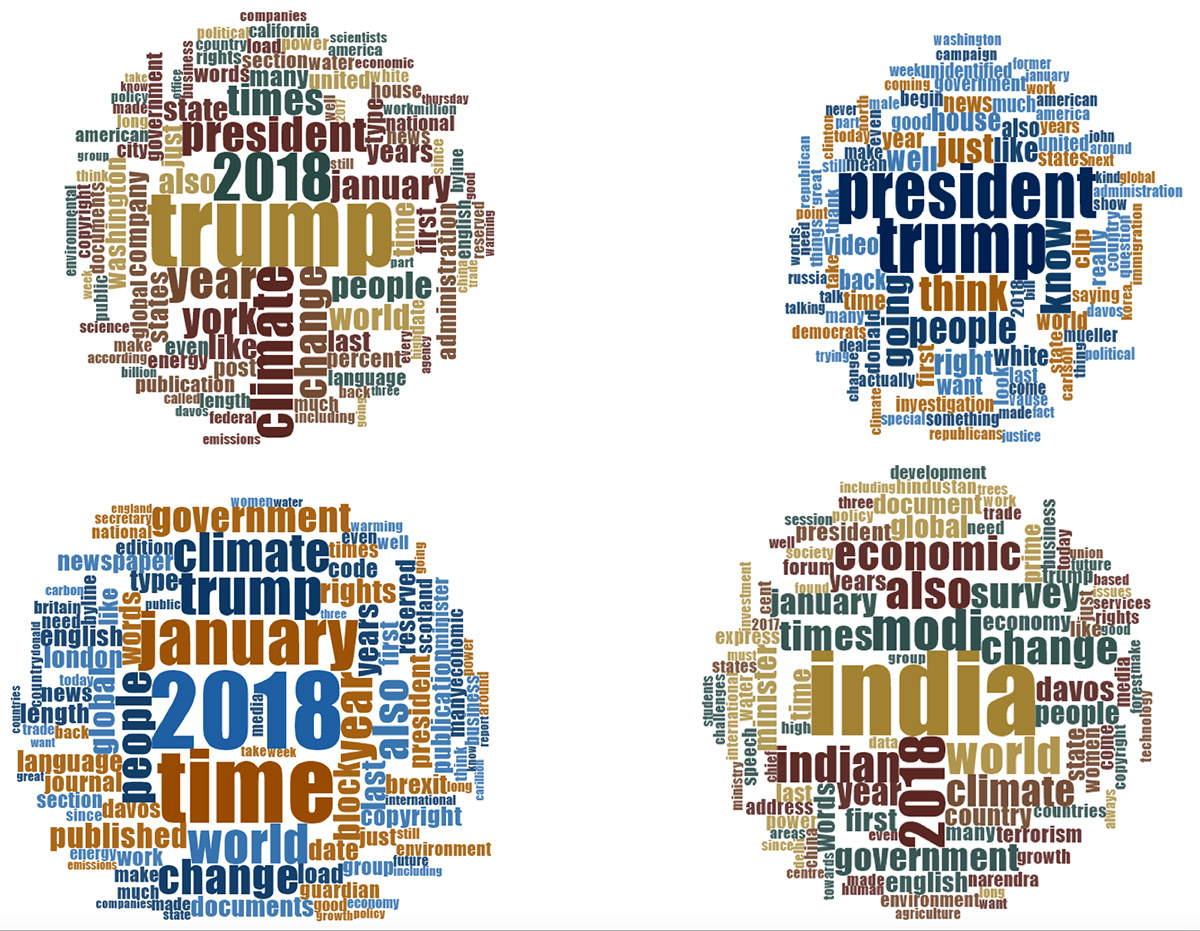

Moving to considerations of content within these searches, Figure 3 shows word frequency data at the country levels in global newspapers and radio, juxtaposed with US newspapers and US television in February 2018.

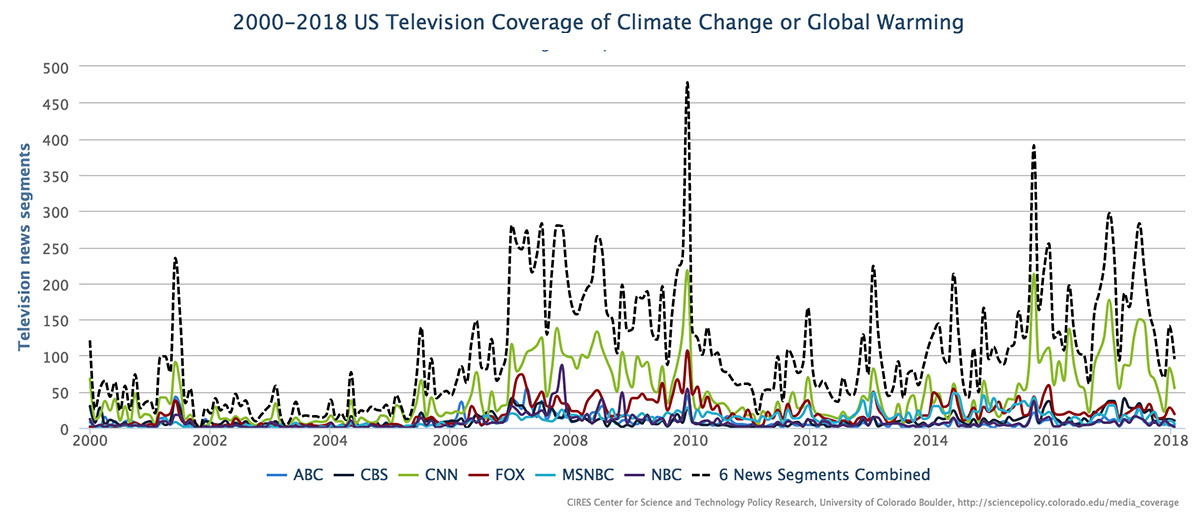

The five newspapers and six television sources in the US showed continuing yet diminishing signs in February of the ‘Trump Dump’ (where media attention that would have focused on other climate-related events and issues instead was placed on Trump-related actions (leaving many other stories untold)). However, analyses of content in media reporting outside the US context show that this pattern of news reporting continues to be limited to the US. To illustrate, in February, US news articles related to climate change or global warming, Trump was invoked 1439 times through the 272 stories this month (a ratio of 5.3 times per article on average) in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, USA Today, and the Los Angeles Times. In US television sources of ABC, CBS, CNN, Fox News Network, MSNBC, and NBC, Trump was mentioned 722 times in 43 news segments (16.8 mentions per segment). In contrast, in the UK press, Trump was mentioned in the Daily Mail & Mail on Sunday, Guardian & the Observer, the Sun, the Daily Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph, the Daily Mirror & Sunday Mirror, the Scotsman & Scotland on Sunday, and the Times & Sunday Times 348 times in 448 February articles (approximately 0.8 mentions per article on average).

That said, diminishing signs are indicated by the ratio in the US, now down from 8.8 times per article and 43 times per television segment in January (drops in these ratios of 40% and 61% respectively). These diminished trends were evident across media publications outside the US as well in February 2018 (e.g. 0.9 times/article in Canada, 0.3 times/article in Australia, 0.2 times/article in New Zealand and 0.3 times/article in Germany). We will see if this declining Trump influence on media coverage of global warming or climate change in US sources and elsewhere continues to decline as 2018 unfolds. However, this current trend can quickly change if the Trump Administration focuses attention on the issues in March and beyond.

Many media accounts in February focused on primarily scientific dimensions of climate change and global warming. For example, early in February a new study in Science magazine by Anthony Pagano and colleagues – perhaps primed by wintry weather in the Northern Hemisphere – found that consumption of high-fat prey by polar bears is becoming scarcer in ice-free conditions, and they therefore are having to work harder to find their calories. Journalist Amina Khan in the Los Angeles Times reported that this research into free-ranging Arctic polar bear behavior and metabolism over a two year period confirmed suspicions that the loss of sea ice detrimentally impacts their health and survival, writing, “they burn calories at a faster rate than previously thought”. Later in February, a considerable amount of media attention focused in on a scientific article in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Steve Nerem (from the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at CU Boulder (also where MeCCO is housed)) and colleagues. They found through examinations of twenty-five years of sea level data that the pace of sea level rise has increased. From the research, Associated Press journalist Seth Borenstein and many others wrote about how the researchers then projected that there would now be a global sea level rise higher than previously expected, of approximately two feet (0.6 meters) by 2100.

Attention paid to political content of coverage during the month was often tethered to decarbonization trends. As one example, a report on increasing wind capacity in Europe garnered widespread media attention. Among stories, journalist Adam Vaughan from The Guardian wrote, “Britain accounted for more than half of the new offshore wind power capacity built in Europe last year, as the sector broke installation records across the continent”. As a second example, the fate of coal generated a number of stories as well. While a study from the US Appalachian Regional Commission noted that coal production in that region has fallen precipitously, other stories covered how US Trump Administration policy action has reversed these trends in the short term. For instance, Journalist Kris Maher from The Wall Street Journal wrote, “Miners in Indiana and other states are getting a small lift from global markets: American companies are shipping more coal to Europe and Asia, helping to stop the years long drop in the number of U.S. mining jobs. The latest job increase runs counter to the long-term decline in coal used to generate electricity in the U.S., as coal-fired power plants are closed in favor of plants that burn cheap, abundant and cleaner natural gas…The stronger export market is translating into a bump in coal-mining jobs”.

Across the globe in February, stories also intersected with the cultural dimensions. For example, a New York Times piece by Maggie Astor entitled ‘No children because of climate change? Some people are considering it’ focused on how an uncertain climate future has played a role in childbearing decisions among interviewees ages 18 to 43 in the US..

Meanwhile in February, coverage relating primarily to ecological and meteorological issues continued to draw attention. To illustrate, continued impacts from hurricane damage – particularly hurricanes Irma and Maria – whipped up media attention. One representative story by writer Tim Craig and photojournalist Bonnie Jo Mount called ‘Shredded roofs, shattered lives’ in TheWashington Post was emblematic of coverage that touched on cultural and societal dimensions and reverberations as they related to ecological/meteorological facets of climate change. In addition, record temperatures in the Artic in late February generated further coverage. For example, in a piece entitled ‘North Pole surges above freezing in the dead of winter, stunning scientists’, Washington Post journalist Jason Samenow wrote, “The Arctic’s temperatures are soaring, with one analysis estimating the North Pole edged above freezing temperatures last weekend even as polar winter continues without sunlight. Although there are no direct temperature measurements at the North Pole, the U.S. Global Forecast System model pegged the temperature as high as 35 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) – more than 50 F (30 C) above normal”.

These cultural and ecological/meteorological infused stories wove back into political dimensions of disaster relief responses now five months since the tragedies struck in the Caribbean Basin. For instance, US National Public Radio’s Greg Allen reported on the weak state of health care services in the US Virgin Islands.

As a general lull in media reporting of climate change or global warming pervades in February 2018, there nonetheless remains an ongoing concern relating to the ‘fierce urgency of now’.

– report prepared by Max Boykoff, Jennifer Katzung and Ami Nacu-Schmidt