by Alison Gilchrist, CSTPR Science Writer

Scientists: what if you knew one weird trick that would increase the number of times your paper was read, cited, and shared? What if that one maneuver also increased the impact your research had on the general public? Other scientists would hate you!

Well, maybe not—but some academic journals might. The ploy that might accomplish all of the above for scientists could also drastically change the scientific publishing industry as we know it: publishing in an open access journal.

“Open access is when research is made openly available to the public to read, reuse, redistribute, and remix in any way that they would like, as long as there is attribution to the original author,” explained assistant professor and CU Boulder librarian Melissa Cantrell. Publishing an open access paper means making that paper readable and downloadable to anyone—your peers, your family, even your second-grade teacher—if they want it.

A particular paper can be made open access, or a dataset. Open access can also describe a journal—the journal Current Zoology is fully open access, for example. A journal can also be a “hybrid” journal, meaning that some of the papers are open access and some are not.

The alternative to open access, “closed access,” describes research that is behind a paywall or that you can only see if you have a subscription. It is the norm in scientific publishing, and the system relies financially on scientists and institutions buying subscriptions to journals. If your institution has bought a subscription to a set of journals, you will be able to see all the papers published by those journals. At CU, this means you have access to the papers from high impact journals like Science, as well as access to more obscure databases like Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Philosophers.

The downsides of closed access publishing are well-captured by the phrase itself. Research is only accessible if you or your institution has already purchased access, and sharing papers or data from these journals is discouraged. Many argue that the closed access system prevents members of the public from viewing research that they are interested in and that their tax dollars have paid for. What if you published a very interesting analysis of the philosopher George Berkeley in the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Philosophers, and nobody was able to read it? Like the famous fallen tree in the forest, the question is: would it even exist?

Open access has become the antidote to these problems. There is a growing movement towards making research more accessible by making it publicly available online, no subscription necessary.

“There have been things that probably qualified as open access for decades,” said Andrew Johnson, Head of Data & Scholarly Communications Services at CU Boulder University Libraries. “But really when people started calling it Open Access—capital O, capital A—which started around 2002, there was a big statement on Open Access called the Budapest Initiative. A lot of people see that as ground zero for the movement.”

The Budapest Open Access Initiative, a public statement supporting and advising open access, arose from a meeting called Open Society Institute. The statement was signed by various advocates for open access and sparked an international movement towards upholding the outlined principles.

After 2002, there were a number of organizations that began to publicly embrace open access—including the National Institutes of Health. The NIH, a major funder of biological research, now makes the peer-reviewed articles it funds publicly available online.

Apart from being required in some cases, publishing in an open access forum can be beneficial to the researchers involved. Perhaps unsurprisingly, papers and data published on open access platforms are cited more frequently and referenced more often (including on platforms such as Wikipedia, demonstrating how important open access is for the general public). This is powerful motivation for researchers to choose open access, as well as being motivation for the public to support more researchers publishing on open access platforms.

“It really helps increase the impact of their work,” said Cantrell. “It helps it reach a wider audience.”

The Center for Science and Technology Policy Research (CSTPR), like most CU Boulder departments, has strong incentives for supporting open access.

“Open access is extremely beneficial for the public, in the way it helps make research more accessible and equitable,” said Cantrell. “Especially because science and technology are really special in terms of how fast things are moving. It’s so important for people to know what’s going on in science and technology.”

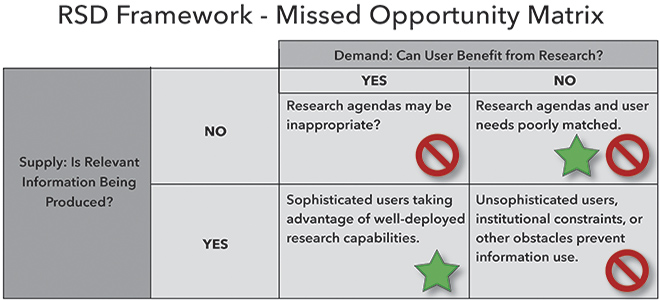

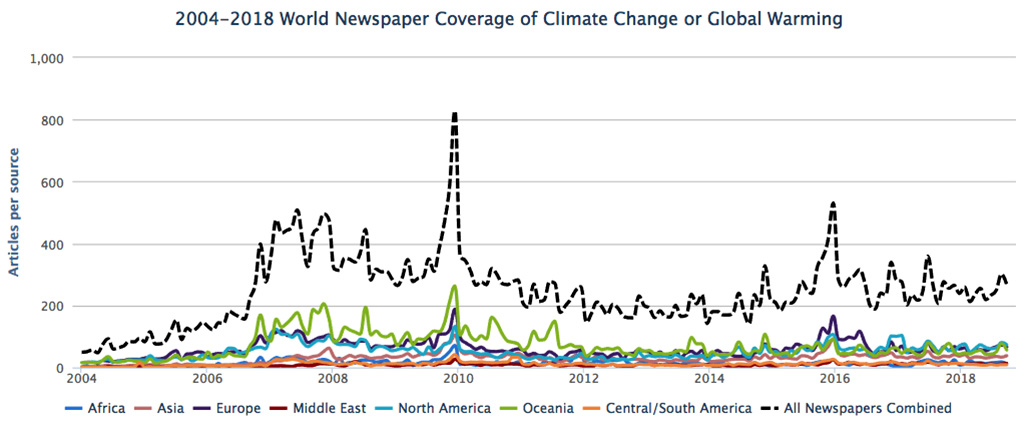

“Open access can apply to data too,” Andrew Johnson elaborated. “And you absolutely have to have access to the data to make policy impacts.” For example, the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) datasets, as well as summaries of the data, have all been made publicly available. This data could help politicians and the general public understand current attitudes about climate change.

But of course, there are detractors of open access, along with some ongoing challenges and downsides. Some scientists claim that open access journals are of dubious quality. This is a generalization: there are high- and low-quality open access journals just like there are high- and low-quality closed access journals. Others point out that all the most competitive, highest regarded journals (those with the highest “impact factor”) are not open access. This is a misrepresentation: open access journals are generally younger than traditional journals, so they haven’t had time to make a name for themselves.

“Outright hostile reactions are few and far between,” said Johnson, “but there’s certainly a lot of skepticism, and I feel like a lot of the time it’s coming from people who are, for one reason or another, heavily invested in the traditional system.”

Open access does have the potential to disrupt traditional publishing. If many researchers chose open access over closed access, the impact factor of well-established journals could be affected. Theoretically those journals could lose subscribers as the open access makes subscriptions unnecessary. We might be a long way off from the point where it seriously damages journals’ profit margins, but it’s certainly not outside the realm of possibility.

“So maybe they are on the editorial board of a closed access journal,” said Johnson. “Or, maybe they’ve had a bad experience with a low-quality open access journal—which of course exist, just like low-quality closed access journals exist.”

Some researchers believe in open access in principle, but shy away from the costs associated with publishing in an open access journal—generally, open access requires that the author of a paper pay a fee to the journal (rather than the cost of publishing be funded by subscribers). This cost can be prohibitive, and open access advocates understand why that is putting people off.

But librarians, including CU Boulder librarians, are fighting the mythmaking and misunderstandings propagated by these skeptics. Universities often have funds available for journal fees so that researchers do not pay out of their own pocket to publish in an open access journal. At CU Boulder, Andrew Johnson and Melissa Cantrell are actively trying to educate researchers about the funds CU Boulder has for this purpose, and about the benefits of open access publishing. As a researcher, you can apply for these funds if you are planning to publish in a journal that is fully open access. If successful, CU Boulder will pay the fees associated with publishing.

Another way they’ve planned to increase awareness of this issue is to celebrate Open Access week, planned for October 22nd-October 28th. This week-long series of events is designed tp bring these open access options to the forefront of people’s minds and remind them of the benefits. As well as general informational seminars, there will be talks about related topics such as accessibility of research.

“There’s a difference between access to research and accessibility,” said Cantrell. She clarified by email that increasing research’s accessibility refers to a wide variety of underserved populations, which includes non-English speakers, “those with learning and non-learning related disabilities, and others.

There will be a group from the department of Theater and Dance who will be doing a digital presentation, and a screening of the documentary Paywall: The Business of Scholarship. Overall, Open Access Week should be an entertaining and enlightening way to celebrate a publishing movement that benefits scientists and the public. This “one weird trick” sounds like clickbait, but it is the future.

Technology Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

by Marilyn Averill

Senior Fellow at Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment

Technology plays a huge role in action on climate change. Implementation of the Paris Agreement will require even more technology-related planning, capacity building, financing, development, and other activities. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) does a huge amount of work on climate technologies (as do many other organizations), but few people are aware of this work or the resources available.

In 2001 the parties to the UNFCCC created an Expert Group on Technology Transfer (EGTT). In 2010 the parties ended the EGTT and constructed a Technology Mechanism (TM) to work on issues relating to the development of climate-related technologies, and the transfer of technologies to developing countries. The Technology Executive Committee (TEC) was set up as the policy arm of the TM. The Climate Technology Centre and Network (CTCN) was created as the implementation arm.

The TEC consists of 20 members who are experts on climate-related technologies. Many also serve as negotiators for their countries. The TEC meets at least twice a year. Observers from countries, international organizations, and civil society are invited to attend, and the meetings are webcast. The photo above shows members, observers, and secretariat staff attending TEC 17 last September.

TEC task forces work with the secretariat to implement the TEC’s rolling workplan. Each task force includes a few people from civil society—something few UNFCCC bodies have allowed.

The website for the TM, TT:CLEAR, provides reports, guidance documents, case studies, and other resources useful to anyone interested in the role that technology plays in climate action, and what the parties to the UNFCCC are trying to do to promote and support technology development and transfer. According to TT:CLEAR, “A climate technology is any equipment, technique, practical knowledge or skill needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or adapt to climate change.”

The CTCN, based in Copenhagen, provides training and technical support to developing countries through workshops, materials, and direct consulting. Developing countries can request assistance with specific issues, such as conducting a technology needs assessment (TNA). Check out the CTCN website for more information and resources across many climate technology sectors.

The “Network” part of CTCN is a broad community of people and institutions with knowledge, skills, and experience about working with climate technologies in developing countries. Read about membership requirements and benefits. CTCN serves as a kind of matchmaker to pair experts with developing countries needs for expertise.

The TEC and the CTCN work closely together to coordinate their separate functions under the TM. They also are increasing their work with other bodies to learn more about their technology issues, to provide resources, and to work together to find effective ways to deal with climate challenges.

Take some time to browse through TT:CLEAR and the CTCN website to see what they have to offer. Chances are good that you will find information useful for your own research.