Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO)

February 2017 Summary

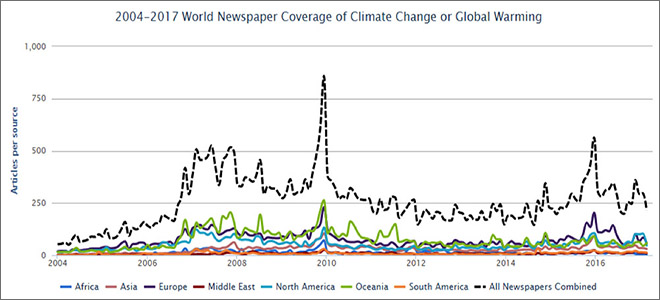

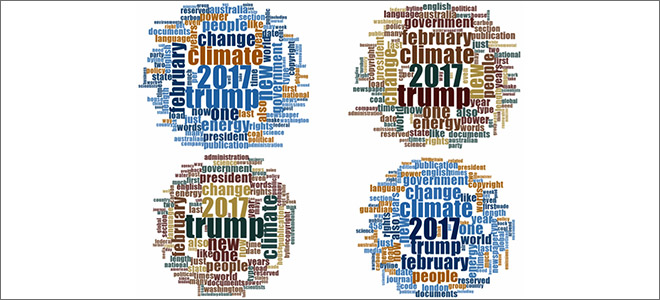

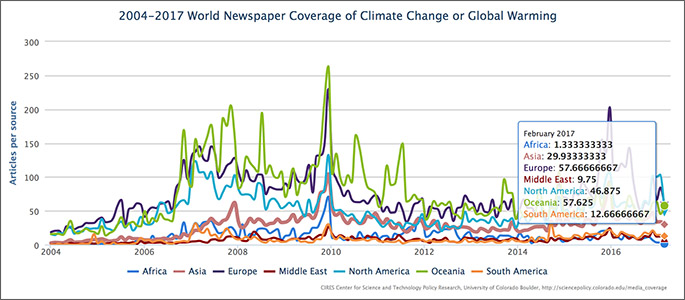

February 2017 saw climate change coverage decrease across the fifty sources in twenty-seven countries around planet Earth (see Figure 1). Coverage of political, scientific, ecological/meteorological, and cultural dimensions of climate change issues dropped 26% globally from the previous month and 23% from the previous February (2016). Compared to January 2017, this decrease was most pronounced in North America with a 55% dip. While the content of coverage in Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom (UK), the United States (US) and around the world continued to place a steady focus on movements of the newly anointed Donald J. Trump Administration in the US (see Figure 2), media attention focused more frequently on a range of other political, social and economic threats and issues during the month of February. Trump Administration movements did not contribute to a bump in coverage overall in February; instead, it was more of a ‘Trump Dump’ where media attention that would have focused on other climate-related events and issues instead was placed on Trump-related actions, leaving many other stories untold in this month.

Figure 1. Media coverage of climate change or global warming in fifty sources across twenty-seven countries in seven different regions around the world through February 2017.

Within dominant political themes for the month, cabinet appointments and US Senate confirmation hearings dotted the February climate change coverage landscape. In particular, the mid-February 52-46 Senate confirmation of former Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt to lead the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) kicked up a number of stories highlighting the controversy behind putting a “seasoned legal opponent of the agency” in charge. Stories also connected to cultural themes, covering protests of Pruitt’s nomination from current and former EPA employees, and from scientists at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting leading up to the confirmation hearing.

Figure 2. Word clouds showing the frequency of words invoked in media coverage of climate change or global warming in Australia (on top left), New Zealand (on top right), the United States (on bottom left) and in the United Kingdom (UK) (on bottom right) in February 2017. The data are from five Australian sources – the The Sydney Morning Herald, Courier Mail & Sunday Mail, The Australian, Daily Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph, and The Age – from three New Zealand sources – the New Zealand Herald, Dominion Post, and The Press – from five US sources – The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, USA Today, and the Los Angeles Times – and from seven UK sources – the Daily Mail & Mail on Sunday, Guardian & The Observer, The Sun, the The Daily Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph, the Daily Mirror & Sunday Mirror, The Scotsman & Scotland on Sunday, and The Times & Sunday Times.

At the political and scientific interface, stories across India, Thailand and Japan in particular focused on carbon tax and new technologies to save energy. For example, a story from the Bangkok Post focused on how a country-wide regulatory shift in new air conditioning technology standards “could reduce the country’s power consumption by 10%”. Around the world, coverage also focused on US-based Trump Administration plans to weaken federal environmental regulations of many sorts. For instances, Hiroko Tabuchi from The New York Times wrote about Republican efforts to dismantle rules that block surface coal mining near US streams and Oliver Milman from The Guardian reported on efforts to target regulations that restrict drilling in US national parks and curb the release of methane. And Juliet Eilperin and Brady Dennis from The Washington Post wrote about Trump administration symbolic and material efforts to move forward on pipeline projects, in particular the Dakota Access Pipeline.

In ecological/meteorological news, stories about heatwaves, fire danger, floods and high temperatures popped up throughout the month around the world. Eryk Bagshaw, Megan Levy and Peter Hannam from The Sydney Morning Herald reported on a heat wave and extreme fire danger, with temperatures reaching 116°F (47°C) in parts of New South Wales, while Joseph Serna and Bettina Boxall from the Los Angeles Times described “epic rain and snow” in California in the month of February. Meanwhile, stories from The Nation in Pakistan (by Azal Zahir) and in The Times of India (by Harveer Dabas) connected threats to megafauna and flora due to rising temperatures and other climate-related pressures, hooked to high temperatures across Asia in February. And news from warming at the poles garnered media attention as well. For examples, Doyle Rice from USA Today covered new data from Antarctica revealing a new record high temperature on the continent, and Robin McKie from the The Observer reported on high Arctic temperatures and new data from the Boulder-based National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) showing record low ice extent in the region.

– report prepared by Max Boykoff, Kevin Andrews, Gesa Luedecke, Meaghan Daly and Ami Nacu-Schmidt

See February 2017 Global & National Scale Updates

See February 2017 Global & National Scale Updates

The UN Needs Science Advice Now More Than Ever

The UN’s Scientific Advisory Board has done pioneering work. If it is not renewed, policy will suffer

by CSTPR Faculty Affiliate, Susan Avery and Maria Ivanova

“Science makes policy out of brick, not straw,” the Scientific Advisory Board to the United Nations secretary-general wrote in its summary report in September 2016. Twenty-six of us, scientists from a range of disciplines and countries, had worked for more than two years to provide advice on science, technology and innovation for sustainable development to the UN secretary-general.

The goal was to articulate scientific input as the then secretary-general, Ban Ki-moon, explored potential policies to address complex and interdependent problems and to point out effective responses. The board advised on issues ranging from the data revolution and the role of science in the Sustainable Development Goals to a Delphi study that identified major “scientific concerns about the future of people and the planet”.

At the time of writing, however, Ban’s successor, the incoming UN secretary-general António Guterres, has been silent on the board’s future. It is imperative that he retain this institutional innovation and strengthen its role and collaborations with UN agencies.

Governments across the world recognise the importance of science for development and for competitiveness. It can identify problems, formulate policies and monitor their implementation. Science, technology and innovation can help provide food and water security and access to energy, and are central to the response to climate change and biodiversity loss. They can identify ways to create jobs, reduce inequality, increase incomes and enhance health and well-being. They should be integral to policy debates and decisions, not an add-on.

The UN created its first Scientific Advisory Board only in 2013, when Ban acted on the recommendation of the High-level Panel on Global Sustainability. Co-chaired by the presidents of Finland and South Africa, Tarja Halonen and Jacob Zuma, the panel recommended the appointment of “a chief scientific adviser or a scientific advisory board with diverse knowledge and experience to advise [the secretary-general] and other organs of the UN”.

In September 2013, Ban established the board by appointing 13 women and 13 men from a broad range of disciplines (one withdrawal and one death have since reduced that number to 24). Much of the board’s work has been pioneering, as was anticipated by the process that created it.

The complexity and scope of contemporary global problems that the UN is expected to resolve require new approaches and closer linkages between science and policy. Science without policy can be scattered and even futile. Policy without science usually fails to accomplish its core goals and undermines confidence that future policy will be better. Read more …