by Jason Delborne, CSTPR Faculty Affiliate

Associate Professor of Science, Policy, and Society at North Carolina State University

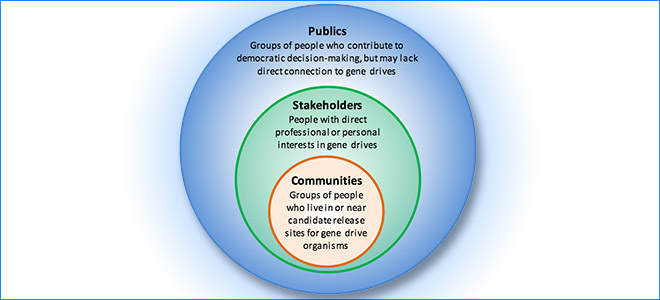

Diagram above from Gene Drives on the Horizon: Advancing Science, Navigating Uncertainty, and Aligning Research with Public Values, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016), page 132

Public engagement has become a key theme in the scientific community. At the AAAS meetings in February of this year, multiple panels focused on the ways that scientists could, and should engage with public audiences. There were tips about communication, lectures about how to engage with audiences that don’t trust scientists, and reminders that scientists have to speak up because “facts don’t speak for themselves.” The planned March for Science, which emerged from something like the scientific grassroots, has now been endorsed by scientific societies and the AAAS, itself. Engagement is in the air.

I applaud all this, or most of it, but I have some concerns. First, some of the excitement around engagement still draws from the deficit model of the public understanding of science. Second, few scientists are talking about the key design elements for engagement efforts. And third, while the outcome of the 2016 presidential election may inspire new attention to the failure of scientific elites to engage broad swaths of the United States, such a focus could also skew our vision for choosing who to engage about what.

The “deficit model” suggests that the best explanation for a lack of support or enthusiasm for science, the scientific community, and “science-based” decisions is a lack of knowledge by non-scientists. If the public – out there – could only understand our science, then they would agree with us! Engagement, under this narrative, becomes then a simple opportunity to teach others what we know so that they will support us (public funding for research) and agree with us (on policies that we see as aligned with scientific knowledge). To engage is to teach and to convince.

It’s not that the deficit model is completely wrong (Sturgis and Allum 2004), or that teaching and convincing are out of bounds for scientists, but I want to argue that engagement stemming from these premises misses a more important element. I like to use the metaphor of grasping hands when I describe engagement. When you grasp someone’s hand, two things happen. First, you touch each other to form a connection, and this connection enables a relationship that is different from reading scientific articles or learning from a website. Engagement is a human event, full of the social cues, personalities, and bodies of people. Second, when you grasp hands with someone else, you both become vulnerable to being moved. This does not mean that every engagement requires scientists to leave their knowledge behind and accept whatever perspectives or beliefs are offered to them, but it does suggest that worthwhile engagement should protect at least the possibility of movement by either or both parties.

This vulnerability connects to my second point about taking design seriously when approaching engagement. Vulnerability comes partly from an attitude of humility – which scientists might bring to many kinds of interactions with public audiences – but it is also a result of design. What is the purpose of engagement? If the purpose is to convince an audience that GMOs are safe or that climate change is real, then it is pretty difficult to grasp hands in any meaningful way. But if the purpose is to learn about how an audience understands your research, what questions they have, what they know that supports or contradicts your interpretations, then you are well on your way to some degree of vulnerability.

Design choices are strategic and they have consequences, so we might as well take them seriously. Here are some of the key questions I attempt to answer when I undertake an engagement activity:

- What are the goals of engagement?

- Who should be engaged, and what can we do to realize that ideal audience?

- What information (including access to experts) would be most helpful to those who are engaged?

- How can we facilitate the most respectful and meaningful exchange of ideas, perspectives, and information?

- What are envisioned outcomes of engagement?

- If engagement is meant to influence decision-making, how can we conduct engagement in a manner that connects to existing networks where such decisions are made?

- How can this engagement allow for learning that influences future engagement?

The third topic I want to address is the potential for the rise to power of the Trump administration to both inspire and skew our attention to public engagement. On one hand, Trump’s electoral victory serves as a key argument for more thoughtful engagement by scientists, who are often painted as elites by media aligned with Trump’s base of support. Studies continue to show that scientists and the well-educated lean Democratic, a partisan reality on full display at the AAAS meeting in Boston. The question is what are we going to do about it?

One response is that we need to target those segments of the population that the Trump campaign activated to win the election. Scientists, who primarily inhabit universities and progressive urban centers, need to reach out to rural, conservative, white voters. What are their concerns, and how can we help them to see the utility of science? Might we even convince them to trust “our” facts? Could we engage them in a way that brings more of them into our professional field to bring a greater diversity of perspectives into our knowledge producing institutions? We can no longer afford for our universities, national laboratories, and regulatory agencies to be demonized by conservatives as liberal bastions, and what better way to counter this trend than to engage with the people we have failed to engage.

Yes. And maybe.

I am prepared to be challenged to engage with audiences of people who do not share many of my values or views of the world. I am supportive of the idea that engaging with new constituencies could be good for scientific credibility and broaden the horizon of scientific inquiry.

But I worry that it could be too easy to shift our meager engagement resources away from the marginalized groups who did not contribute to Trump’s electoral victory: people of color, immigrants, Muslims, the LGBTQ community, the urban poor, the homeless, and disabled persons. These are also communities that science has not historically served particularly well, or engaged with much passion and perseverance. And these are the communities that are more at risk under the proposed and emerging policies of the White House. My point is for the scientific community to avoid becoming fascinated by the need to engage the Trump voter at the expense of marginalized communities who do not have someone representing their interest in the most powerful office in the world.

Let engagement ring, but let it not be deafening.

Sturgis, P., & Allum, N. (2004). Science in society: re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Understanding of Science, 13(1), 55–74.

The Ring of Engagement

by Jason Delborne, CSTPR Faculty Affiliate

Associate Professor of Science, Policy, and Society at North Carolina State University

Diagram above from Gene Drives on the Horizon: Advancing Science, Navigating Uncertainty, and Aligning Research with Public Values, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016), page 132

Public engagement has become a key theme in the scientific community. At the AAAS meetings in February of this year, multiple panels focused on the ways that scientists could, and should engage with public audiences. There were tips about communication, lectures about how to engage with audiences that don’t trust scientists, and reminders that scientists have to speak up because “facts don’t speak for themselves.” The planned March for Science, which emerged from something like the scientific grassroots, has now been endorsed by scientific societies and the AAAS, itself. Engagement is in the air.

I applaud all this, or most of it, but I have some concerns. First, some of the excitement around engagement still draws from the deficit model of the public understanding of science. Second, few scientists are talking about the key design elements for engagement efforts. And third, while the outcome of the 2016 presidential election may inspire new attention to the failure of scientific elites to engage broad swaths of the United States, such a focus could also skew our vision for choosing who to engage about what.

The “deficit model” suggests that the best explanation for a lack of support or enthusiasm for science, the scientific community, and “science-based” decisions is a lack of knowledge by non-scientists. If the public – out there – could only understand our science, then they would agree with us! Engagement, under this narrative, becomes then a simple opportunity to teach others what we know so that they will support us (public funding for research) and agree with us (on policies that we see as aligned with scientific knowledge). To engage is to teach and to convince.

It’s not that the deficit model is completely wrong (Sturgis and Allum 2004), or that teaching and convincing are out of bounds for scientists, but I want to argue that engagement stemming from these premises misses a more important element. I like to use the metaphor of grasping hands when I describe engagement. When you grasp someone’s hand, two things happen. First, you touch each other to form a connection, and this connection enables a relationship that is different from reading scientific articles or learning from a website. Engagement is a human event, full of the social cues, personalities, and bodies of people. Second, when you grasp hands with someone else, you both become vulnerable to being moved. This does not mean that every engagement requires scientists to leave their knowledge behind and accept whatever perspectives or beliefs are offered to them, but it does suggest that worthwhile engagement should protect at least the possibility of movement by either or both parties.

This vulnerability connects to my second point about taking design seriously when approaching engagement. Vulnerability comes partly from an attitude of humility – which scientists might bring to many kinds of interactions with public audiences – but it is also a result of design. What is the purpose of engagement? If the purpose is to convince an audience that GMOs are safe or that climate change is real, then it is pretty difficult to grasp hands in any meaningful way. But if the purpose is to learn about how an audience understands your research, what questions they have, what they know that supports or contradicts your interpretations, then you are well on your way to some degree of vulnerability.

Design choices are strategic and they have consequences, so we might as well take them seriously. Here are some of the key questions I attempt to answer when I undertake an engagement activity:

The third topic I want to address is the potential for the rise to power of the Trump administration to both inspire and skew our attention to public engagement. On one hand, Trump’s electoral victory serves as a key argument for more thoughtful engagement by scientists, who are often painted as elites by media aligned with Trump’s base of support. Studies continue to show that scientists and the well-educated lean Democratic, a partisan reality on full display at the AAAS meeting in Boston. The question is what are we going to do about it?

One response is that we need to target those segments of the population that the Trump campaign activated to win the election. Scientists, who primarily inhabit universities and progressive urban centers, need to reach out to rural, conservative, white voters. What are their concerns, and how can we help them to see the utility of science? Might we even convince them to trust “our” facts? Could we engage them in a way that brings more of them into our professional field to bring a greater diversity of perspectives into our knowledge producing institutions? We can no longer afford for our universities, national laboratories, and regulatory agencies to be demonized by conservatives as liberal bastions, and what better way to counter this trend than to engage with the people we have failed to engage.

Yes. And maybe.

I am prepared to be challenged to engage with audiences of people who do not share many of my values or views of the world. I am supportive of the idea that engaging with new constituencies could be good for scientific credibility and broaden the horizon of scientific inquiry.

But I worry that it could be too easy to shift our meager engagement resources away from the marginalized groups who did not contribute to Trump’s electoral victory: people of color, immigrants, Muslims, the LGBTQ community, the urban poor, the homeless, and disabled persons. These are also communities that science has not historically served particularly well, or engaged with much passion and perseverance. And these are the communities that are more at risk under the proposed and emerging policies of the White House. My point is for the scientific community to avoid becoming fascinated by the need to engage the Trump voter at the expense of marginalized communities who do not have someone representing their interest in the most powerful office in the world.

Let engagement ring, but let it not be deafening.

Sturgis, P., & Allum, N. (2004). Science in society: re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Understanding of Science, 13(1), 55–74.