Kaitlin McCreery (Mechanical Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder), pictured right in the above photo, was one of the 2018 winners for the AAAS Student Workshop Competition. Below are comments from her workshop experience.

I left my snow boots by the door as I departed for Denver International Airport at 4:30 a.m. on a Sunday morning, thinking the forecasted snow was a Southern bluff. From March 18 to 21, I navigated the streets and government buildings of our nation’s capitol with a fellow CU-Boulder graduate student, Julia Bakker-Arkema and a graduate student representative from Colorado State, Amanda Koch. We were three of a contingent of 193 graduate students from around the country that the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) policy workshop called “Making Our C.A.S.E.” (Catalyzing Advocacy in Science and Engineering). The goal of this annual workshop is to inform scientists how funding for science is determined by Congress, how science serves the interests of the public, and how scientists can integrate these two aspects.

Why do we need young scientists in Washington to advocate for funding? It is important to remember who is running our country, and their education background. For instance, 18 members of the House have no post-secondary education. Fifty-five percent of the Senate holds law degrees. Just 22 Representatives and 2 Senators have doctoral degrees. In all of Congress, there is one physicist, one chemist, and eight engineers. But there is no significant advantage of having a science background in Congress, as it serves two purposes: passing laws and writing checks for nearly every social and economic issue that our nation faces. If scientists want more funding, we need to show them who we are, and ask for it.

Graduate students from every state in the continental United States packed the auditorium in the AAAS Headquarters on a Monday morning. Matthew Hourihan, Director of the AAAS Research and Development (R&D) Budget and Policy Program, gave us a detailed look at the federal budget process. We heard from Rush Holt, CEO of AAAS and former U.S. Representative for New Jersey, as he discussed why scientists have untapped potential for political influence. Graduate students are some of the best science advocates because we do the grunt work in academic research while being paid with federal dollars. We have passion behind our commitment to research, and our representatives want to go to bat for us.

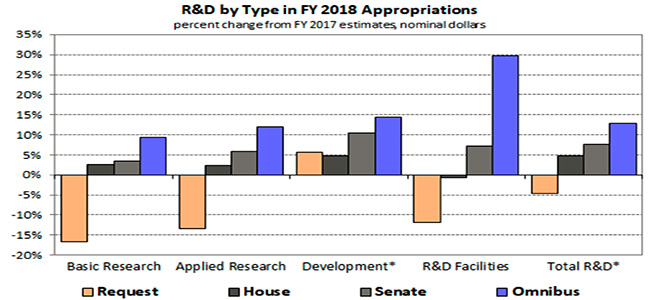

Some of what I learned about the federal budget surprised me. In general, Defense spending accounts for just under half of R&D expenditures. The National Science Foundation—which pays my salary, through a graduate training grant—makes up a relatively small portion of the budget. For the life sciences, the largest source of funding is the National Institutes of Health. The buzz term of the week in Washington was “appropriation season,” as the federal government was scheduled to shut down in three days if a spending bill was not signed into law. Congressmen and their staffers—many of whom were in their twenties—were charged with the task of writing and refining the spending bill that influences every aspect of the American economy.

As we prepared for our meetings, I wondered: as a scientist, what impact can I make? There are so many issues that I feel passionate about, from climate change to increasing research on gun control measures. I desired to tackle all of them with this unique opportunity. During lunch, the day before our meetings with Colorado congressmen, I approached Rush Holt (CEO of AAAS) to gain insight, and he boiled down his decades of experience while we hunched over our boxed lunches. He asked me three key questions: “First, who do you want them to think you are? Second, what do you want them to do? Third, what can you thank them for?” These questions made an excellent point. These brief meetings would be most impactful if we represent a concise group of people with a clear message: increase funding for scientists like us. Give them a face representing the people funded by the NSF.

On our final morning in Washington, I wished that I was wearing snow-appropriate shoes as we dashed out of our cab, through the snowy slush, and up the stairs of the Longworth House Office Building which houses all of the offices of the House of Representatives. We first met with congressional staffers in Jared Polis’ office, who were incredibly friendly and receptive. As we left for our next meeting, Representative Polis himself stepped into the hallway and called to us, “Hello, scientists!” We quickly thanked him for his commitment to funding research and snapped a photo before he disappeared to attend a hearing.

We followed a Congressional staffer down to the basement and hurriedly walked through the tunnel beneath the Capitol to get to our meetings with the staffers of Senators Gardner and Bennett. Each of their offices were decadently decorated with local Colorado art and memorabilia, including a Broncos poster and oil paintings of Aspen trees. Since the Senators were in hearings, we discussed federal R&D funding with young, educated, overworked staffers in decadent offices. Meeting with these staffers was inspiring in its own rite, and our discussions reminded me that we are all trying to find the optimal way we can serve our society. Spending time in these offices reinforced the idea that Congressmen work for their constituents, as our 15-minute meeting was on a long list of issues they were to address that day from constituents that traveled to Washington offices. They listened to our stories, asked about our research, and asked about how federal dollars impact our work. The staffers assured us that our representatives were opposed to cuts to scientific research, and we just needed to remain optimistic.

Just a few days after I returned to Colorado, my endless scrolling on Twitter abruptly froze when I saw an omnibus bill was sitting on the President’s desk waiting to be signed. The bill contained a 12.8 percent increase in funding for research and development, and is now law. We were fortunate to have nearly 200 student scientists strolling through the halls on the Hill advocating for research funding during a critical time in the bill’s passage. I envision a lot more nerds in Washington in upcoming years to conserve our momentum.

Reflections from the AAAS “Catalyzing Advocacy in Science and Engineering” Workshop

Kaitlin McCreery (Mechanical Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder), pictured right in the above photo, was one of the 2018 winners for the AAAS Student Workshop Competition. Below are comments from her workshop experience.

I left my snow boots by the door as I departed for Denver International Airport at 4:30 a.m. on a Sunday morning, thinking the forecasted snow was a Southern bluff. From March 18 to 21, I navigated the streets and government buildings of our nation’s capitol with a fellow CU-Boulder graduate student, Julia Bakker-Arkema and a graduate student representative from Colorado State, Amanda Koch. We were three of a contingent of 193 graduate students from around the country that the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) policy workshop called “Making Our C.A.S.E.” (Catalyzing Advocacy in Science and Engineering). The goal of this annual workshop is to inform scientists how funding for science is determined by Congress, how science serves the interests of the public, and how scientists can integrate these two aspects.

Why do we need young scientists in Washington to advocate for funding? It is important to remember who is running our country, and their education background. For instance, 18 members of the House have no post-secondary education. Fifty-five percent of the Senate holds law degrees. Just 22 Representatives and 2 Senators have doctoral degrees. In all of Congress, there is one physicist, one chemist, and eight engineers. But there is no significant advantage of having a science background in Congress, as it serves two purposes: passing laws and writing checks for nearly every social and economic issue that our nation faces. If scientists want more funding, we need to show them who we are, and ask for it.

Graduate students from every state in the continental United States packed the auditorium in the AAAS Headquarters on a Monday morning. Matthew Hourihan, Director of the AAAS Research and Development (R&D) Budget and Policy Program, gave us a detailed look at the federal budget process. We heard from Rush Holt, CEO of AAAS and former U.S. Representative for New Jersey, as he discussed why scientists have untapped potential for political influence. Graduate students are some of the best science advocates because we do the grunt work in academic research while being paid with federal dollars. We have passion behind our commitment to research, and our representatives want to go to bat for us.

Some of what I learned about the federal budget surprised me. In general, Defense spending accounts for just under half of R&D expenditures. The National Science Foundation—which pays my salary, through a graduate training grant—makes up a relatively small portion of the budget. For the life sciences, the largest source of funding is the National Institutes of Health. The buzz term of the week in Washington was “appropriation season,” as the federal government was scheduled to shut down in three days if a spending bill was not signed into law. Congressmen and their staffers—many of whom were in their twenties—were charged with the task of writing and refining the spending bill that influences every aspect of the American economy.

As we prepared for our meetings, I wondered: as a scientist, what impact can I make? There are so many issues that I feel passionate about, from climate change to increasing research on gun control measures. I desired to tackle all of them with this unique opportunity. During lunch, the day before our meetings with Colorado congressmen, I approached Rush Holt (CEO of AAAS) to gain insight, and he boiled down his decades of experience while we hunched over our boxed lunches. He asked me three key questions: “First, who do you want them to think you are? Second, what do you want them to do? Third, what can you thank them for?” These questions made an excellent point. These brief meetings would be most impactful if we represent a concise group of people with a clear message: increase funding for scientists like us. Give them a face representing the people funded by the NSF.

On our final morning in Washington, I wished that I was wearing snow-appropriate shoes as we dashed out of our cab, through the snowy slush, and up the stairs of the Longworth House Office Building which houses all of the offices of the House of Representatives. We first met with congressional staffers in Jared Polis’ office, who were incredibly friendly and receptive. As we left for our next meeting, Representative Polis himself stepped into the hallway and called to us, “Hello, scientists!” We quickly thanked him for his commitment to funding research and snapped a photo before he disappeared to attend a hearing.

We followed a Congressional staffer down to the basement and hurriedly walked through the tunnel beneath the Capitol to get to our meetings with the staffers of Senators Gardner and Bennett. Each of their offices were decadently decorated with local Colorado art and memorabilia, including a Broncos poster and oil paintings of Aspen trees. Since the Senators were in hearings, we discussed federal R&D funding with young, educated, overworked staffers in decadent offices. Meeting with these staffers was inspiring in its own rite, and our discussions reminded me that we are all trying to find the optimal way we can serve our society. Spending time in these offices reinforced the idea that Congressmen work for their constituents, as our 15-minute meeting was on a long list of issues they were to address that day from constituents that traveled to Washington offices. They listened to our stories, asked about our research, and asked about how federal dollars impact our work. The staffers assured us that our representatives were opposed to cuts to scientific research, and we just needed to remain optimistic.

Just a few days after I returned to Colorado, my endless scrolling on Twitter abruptly froze when I saw an omnibus bill was sitting on the President’s desk waiting to be signed. The bill contained a 12.8 percent increase in funding for research and development, and is now law. We were fortunate to have nearly 200 student scientists strolling through the halls on the Hill advocating for research funding during a critical time in the bill’s passage. I envision a lot more nerds in Washington in upcoming years to conserve our momentum.