By NOAA Communications

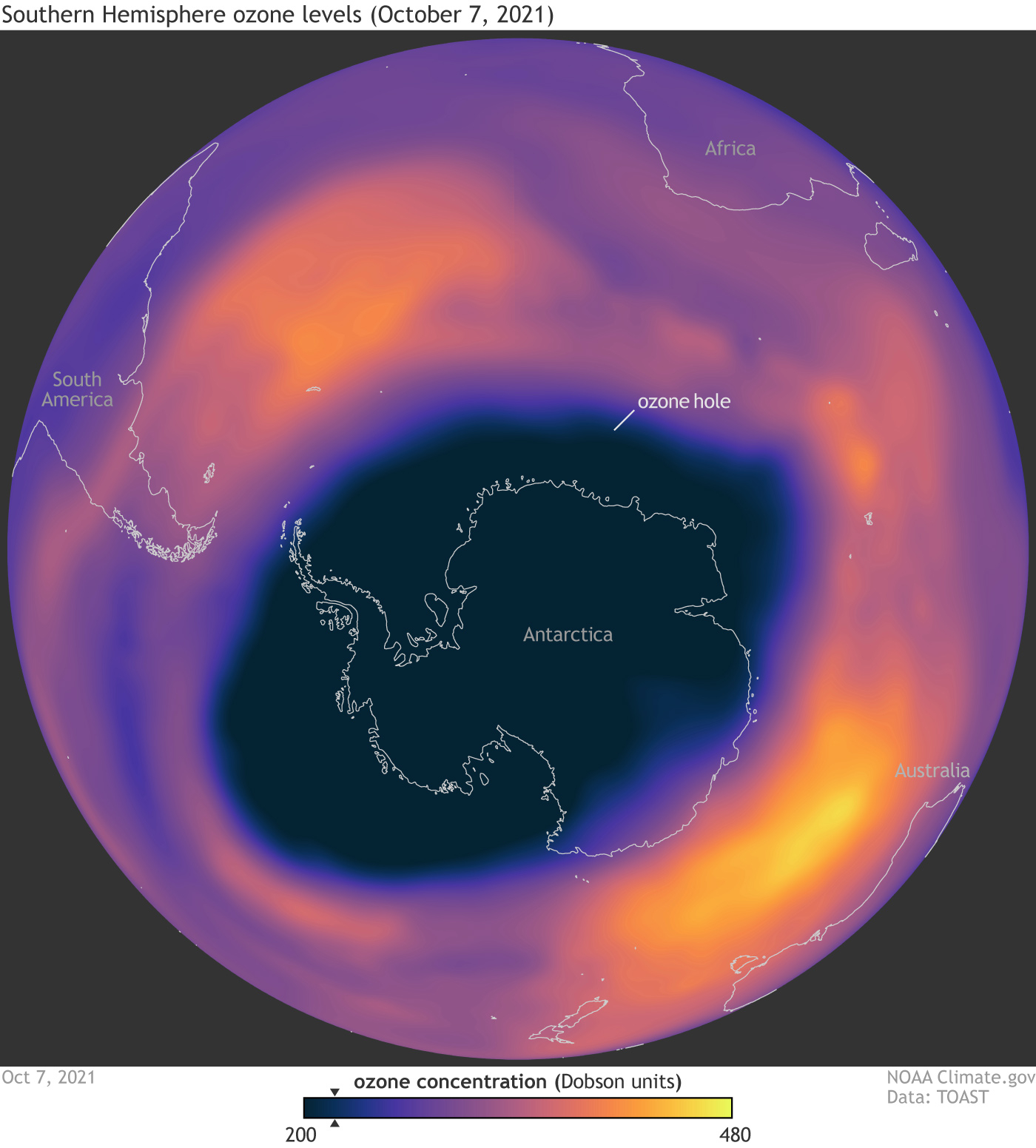

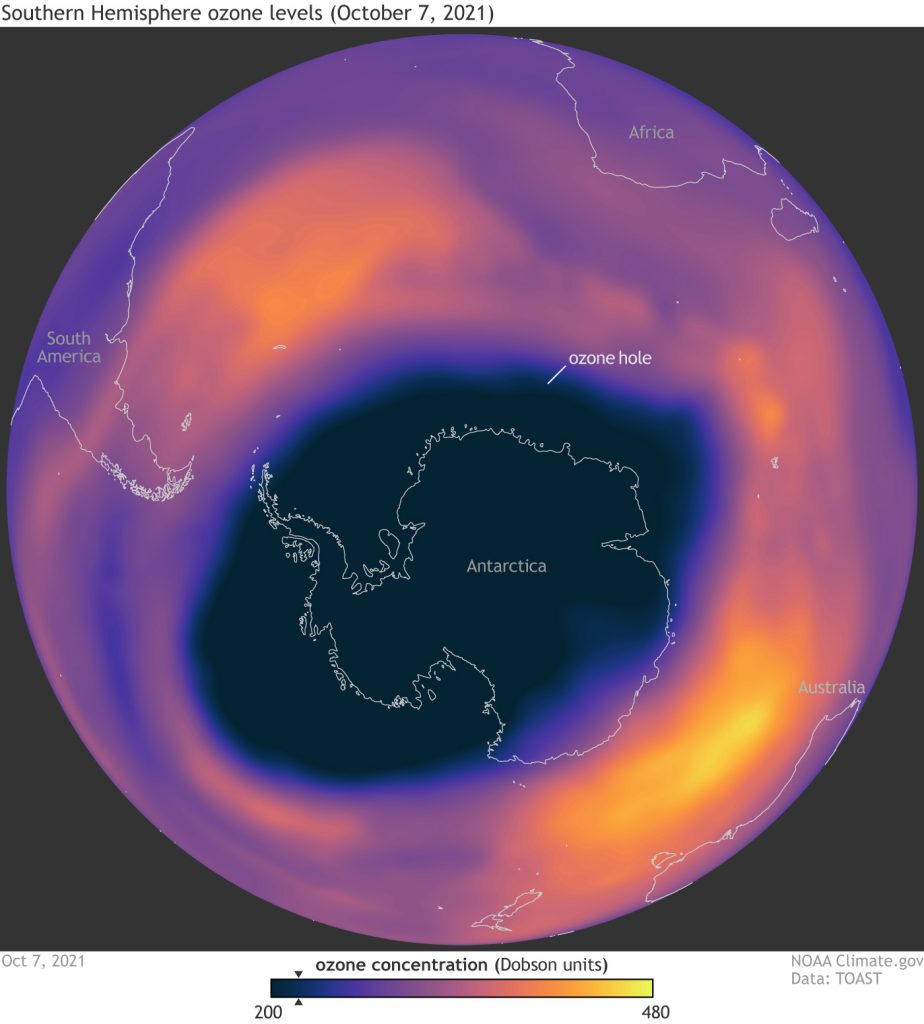

The 2021 Antarctic ozone hole reached its maximum area on October 7 and ranks 13th largest since 1979, scientists from NOAA and NASA reported today. This year’s ozone hole developed similarly to last year’s: A colder-than-usual Southern Hemisphere winter led to a deep and larger-than-average hole that will likely persist into November or early December.

“This is a large ozone hole because of the colder than average 2021 stratospheric conditions, and without a Montreal Protocol, it would have been much larger,” said Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth Sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

What we call the ozone hole is a thinning of the protective ozone layer in the stratosphere (the upper layer of Earth’s atmosphere) above Antarctica that begins every September. Chlorine and bromine derived from human-produced compounds are released from reactions on high-altitude polar clouds. The chemical reactions then begin to destroy the ozone layer as the sun rises in the Antarctic at the end of winter.

NOAA and NASA researchers detect and measure the growth and break up of the ozone hole with satellite instruments aboard Aura, Suomi-NPP and NOAA-20 satellites.

This year, NASA satellite observations determined the ozone hole reached a maximum of 9.6 million square miles (24.8 million square kilometers)—roughly the size of North America—before beginning to shrink in mid-October. Colder-than-average temperatures and strong winds in the stratosphere circling Antarctica contributed to the hole’s size.

NOAA scientists at the South Pole Station record the ozone layer’s thickness by releasing weather balloons carrying ozone-measuring instruments called ozonesondes that measure the varying ozone concentrations as the balloon rises into the stratosphere. CIRES researchers at NOAA are critical to the international effort to understand the South Pole’s seasonal ozone hole and to anticipate its future.

This story was written by NOAA Communications. Read the full story here.