By NOAA Communications

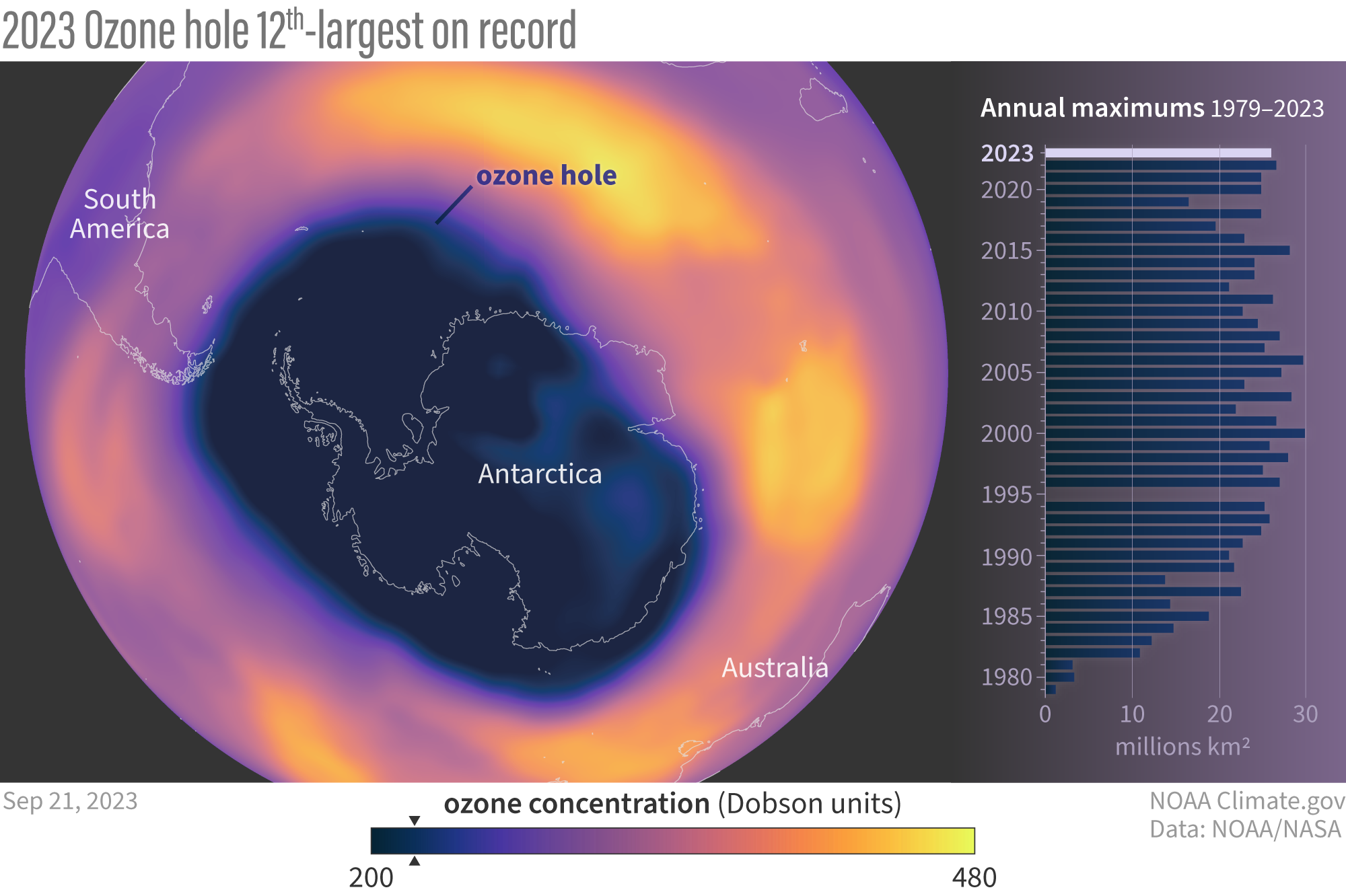

The 2023 Antarctic ozone hole reached its maximum size at 10 million square miles (26 million square kilometers) on September 21, which ranks as the 12th largest since 1979, according to annual satellite and balloon-based measurements made by NOAA and NASA.

During the peak of the ozone depletion season from September 7 to October 13, the hole this year averaged 8.9 million square miles (23.1 million square kilometers), approximately the size of North America.

“It’s a very modest ozone hole,” said Paul Newman, leader of NASA’s ozone research team and chief scientist for Earth sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “Declining levels of human-produced chlorine compounds, along with help from active Antarctic stratospheric weather slightly improved ozone levels this year.”

The ozone layer acts like Earth’s natural sunscreen, as this portion of the stratosphere shields our planet from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. A thinning ozone layer means less protection from UV rays, which can cause sunburns, cataracts and skin cancer in humans.

Every September, the ozone layer thins to form an “ozone hole” above the Antarctic continent. Scientists use the term “ozone hole” as a metaphor for the area in which ozone concentrations above Antarctica drop well below the historical threshold of 220 Dobson Units. Scientists first reported evidence of ozone depletion in 1985 and have tracked Antarctic ozone levels every year since 1979.

Antarctic ozone depletion occurs when human-made chemicals containing chlorine and bromine first rise into the stratosphere. These chemicals are broken down and release their chlorine and bromine to initiate chemical reactions that destroy ozone molecules. The ozone-depleting chemicals, including chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), were once widely used in aerosol sprays, foams, air conditioners, fire suppressants and refrigerators. CFCs, the main ozone-depleting gases, have atmospheric lifetimes of 50 to over 100 years.

“Although the total column ozone is never zero, in most years, we will typically see zero ozone at some altitudes within the stratosphere over the South Pole,” said NOAA Research Chemist Bryan Johnson, project leader for the Global Monitoring Laboratory’s ozonesonde group. “This year, we observed about 95% depletion where we often see near 100% loss of ozone within the stratosphere.”

The 1987 Montreal Protocol and subsequent amendments banned the production of CFCs and other ozone-destroying chemicals worldwide by 2010. The resulting reduction of emissions has led to a decline in ozone-destroying chemicals in the atmosphere and signs of stratospheric ozone recovery.

NOAA and NASA researchers monitor the ozone layer over the pole and globally using instruments aboard NASA’s Aura, NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP and NOAA-20 satellites. Aura’s Microwave Limb Sounder also estimates levels of ozone-destroying chlorine.

Scientists also track the average amount of depletion by measuring the concentration of ozone inside the hole. At NOAA’s South Pole Baseline Atmospheric Observatory, scientists measure the layer’s thickness by releasing weather balloons carrying ozonesondes and by making ground-based measurements with a Dobson spectrophotometer. NOAA’s measurements showed a low value of 111 Dobson Units over the South Pole on October 3. NASA’s measurements, averaged over a wider area, recorded a low of 99 Dobson Units on the same date.

In 1979, the average concentration above Antarctica was 225 Dobson Units; by 1989, it had plummeted to 127 Dobson Units.

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano — which violently erupted in January 2022 and blasted an enormous plume of water vapor into the stratosphere — likely contributed to this year’s substantial ozone depletion. That water vapor likely enhanced ozone-depletion reactions over the Antarctic early in the season.

“If Hunga Tonga hadn’t gone off, the ozone hole would likely be smaller this year,” Newman said. “We know the eruption got into the Antarctic stratosphere, but we cannot yet quantify its full impact to the ozone hole.”

Learn more about NOAA’s Antarctic ozone research.

This story was written by NOAA Communications.