Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO)

January 2017 Summary

January ushered in a new era for many things, including media attention to climate change. As many around the world braced for a new phase of approaches to science and the environment by the United States (US) Trump administration – who took up power on January 20th – stories focused largely on political and policy dimensions of climate change this month.

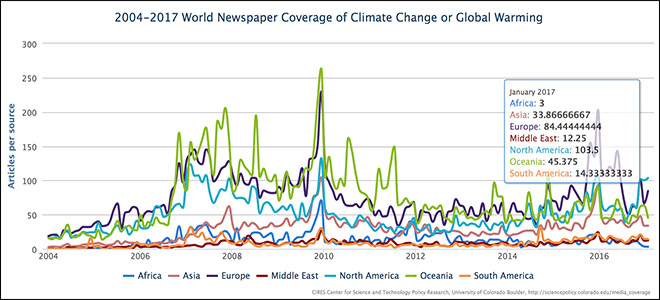

Coverage of climate change and global warming increased most prominently in the US this month, with coverage up 13% from December 2016, and 117% from the previous January. Numbers across all sources in twenty-seven countries showed a 2% increase from December 2016 overall.

A larger majority of stories appearing in US media and around the world surrounded the election of Donald J. Trump in November 2016. Reverberations throughout the country and around the world kicked up coverage. Examples included stories on Trump’s first Executive Orders re-initiating Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipeline projects, and articles on how funding would be curtailed in key federal agencies. Actions, and threats like these, sparked media attention.

To illustrate, Ian Austen and Clifford Krauss from The New York Times reported how for Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Trump’s “revival of Keystone XL upsets a balancing act”. Stephen Mufson and Brady Dennis at The Washington Post reported on how the White House website’s energy pages, which went up within moments of Trump’s inauguration, removed references to combating climate change, a topic that had been featured prominently on the site under President Barack Obama. Betsy McKay from The Wall Street Journal reported that Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said it recently postponed a gathering it had planned to hold next month on the effects of climate change on health, and Coral Davenport from The New York Times reported on a freeze on federal grant spending at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Departments of the Interior, Agriculture and Health and Human Services as well as other government agencies.

Stories in January 2017 about Trump nominations for key posts in the administration – particularly for Secretary of State (former ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson), EPA Administrator (Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt), Secretary of the Department of Interior (Montana Congressman Ryan Zinke) and Secretary of the Department of Energy (former Texas Governor Rick Perry) – focused mainly on worrisome dimensions of these appointments for those who care about climate and environmental protection, justice and human well-being among other things. Moreover, some media pieces also addressed cultural dimensions regarding how climate concerns were voiced in Women’s marches across the world on January 21st, and (mainly in US coverage) how ‘alt’ Twitter accounts cropped up from US National Park Services and other US agency spin-offs to communicate #climatefacts and dismay about Trump Administration plans for shifts in science, environment and climate policy engagements.

So as Barack Obama and his administration vacated the White House, media attention was paid to Donald Trump’s and his aides’ promises for swift and aggressive action to dismantle and block Obama’s climate-related policies and actions, such as incorporating the social cost of carbon to project planning and Clean Power plan regulations. Media treatments also covered how Trump administration behaviors served to embolden Republican legislative officials in the House of Representatives and in the Senate, where the elimination of regulations on coal mining near streams and rules to reduce methane emissions were said to be prioritized in the next Congressional sessions. On January 4, Chelsea Harvey from The Washington Post wrote “As a new Congress convenes this week, regulatory reform is the rage, and the upshot seems to be that at least a few of President Obama’s environmental regulations could be dismantled quickly by the Republican Congress, with President-elect Donald Trump’s approval”. Read more …

Climate Change: The Discovery of a Grand Societal Challenge

by Julia Schubert

Fulbright Doctoral Visiting Scholar at CIRES Center for Science and Technology Policy Research

University of Colorado at Boulder

(Image above: Oldest series of weather maps in the United States. January 30, 1843. Produced by James Pollard Espy. Source: Image ID: wea05013, NOAA’s National Weather Service (NWS) Collection.)

Climate change is arguably one of the most prominent and pressing problems of our time. While the atomic threat dominated the 1960s, and awareness of environmental risks arose predominantly in the 1970s, anthropogenic climate change significantly shapes the beginning of the 21st century as its defining challenge. But how exactly was this issue of climate change discovered? How did it emerge as the epitome of a modern ‘Grand Societal Challenge’ as displayed in countless political pamphlets and organizational mission statements? And, going even further, how do societal problems in general arise?

The simple answer is: We fabricate them. Or, more precisely, they are historically and culturally contingent – building on observations shaping and institutions stabilizing them. These contingent and fragile problem ‘framings’ are thus defined by distinct societal (e.g. religious, scientific, political or economic) observations. And the assertiveness of these observations is in turn dependent on their stabilization in respective institutions, perpetuating a distinct problem-frame. Following this perspective, problems are far from being simply given. Retracing the diverse historical trajectories of climate change as a modern ‘Grand Challenge’, thus illustrates the fundamentally social construction of societal problems. This, of course, does not question or even regard the physical underpinnings of anthropogenic climate change. It rather emphasizes that we are fundamentally shaping its necessarily social reality and therein its configuration as a ‘Grand Societal Challenge’.

Changing and disruptive climatic conditions were observed as early as at the beginning of the 17th century (cf. Parker 2013), some scholars even argue for first observations of climatic change being made in antiquity (cf. Fleming 1998: 137). Importantly differing from modern observations of anthropogenic climate change, however, at the time only isolated catastrophic incidents were captured, rather than a global trend. These early disruptive climatic events such as ‘the year without a summer’ in 1814 were largely attributed to the sphere of the gods. Catastrophic climatic change, in its historical antecedent, was observed and stabilized as a religious problem (see also Hulme 2014: 12).

For early and colonial America, climate change was a matter of national pride and an essential component of the emerging Republican national ideal. The vision was that clearing and cultivating the land would promote a warmer, less variable, and healthier climate. Thomas Jefferson was already a pronounced advocate of comprehensive meteorological measurements – yet without reliable instruments or sponsoring institutions (cf. Fleming 1998: 33). Only in the late 19th century scholars such as Svante Arrhenius (1896, 1908) and Nils Gustaf Ekholm (1901) began to systematically explore the relation of climate and society—tabulating, charting, and mapping their observations and the possibility of global anthropogenic climate change. The establishment of national weather services in Europe, Russia, and the United States allowed for the further standardization of climatic observations. Later, this led to international cooperation and even the establishment of global observation systems, significantly broadening its geographic scope (cf. Fleming 1998: 41). Thus, based on the invention of meteorological observation systems and statistical analysis, a first scientific picture of anthropogenic climate change had been stabilized, discovering and addressing it as a physical phenomenon. A pressing problem, however, was not yet in sight.

It was not before the 1950s, that global warming appeared on the public agenda as a first problematic version of anthropogenic climate change, immediately followed by the discussion of global cooling and the dawn of a new ice age in the 1970s. Again, scientific observation was of essence here and the cooling hypothesis was rather quickly rejected. At the end of the 20th century this problematic observation of global anthropogenic climate change was institutionalized – a final essential step in the discovery of anthropogenic climate change as a ‘Grand Societal Challenge’. Milestones in this certification of the problem as a global issue were, for example, the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988 and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992.

Building on this institutionalization of climate change as a pressing societal problem, various responses were suggested as viable and legitimate: From the scientific challenge posed by the urgent need for better observation systems, or the political challenge of coordinating climate-friendly behavior, to the recently declared technological challenge of actively engineering the climate system to halt dangerous climate change – in each of these versions, climate change is defined as a distinct societal challenge.

Summing up, this short account of the discovery of climate change as a ‘Grand Societal Challenge’ illustrates the complex social presuppositions aiding in the historical evolution, emergence, and addressing of societal problems: Beginning with antecedent religious observations of catastrophic climatic variations, and initial meteorological measuring efforts driven by national political ideals, to the emergence of a first scientific picture of anthropogenic climate change, global warming (and cooling) finally emerged as a ‘Grand Societal Challenge’. Thus, throughout its history, the fragile problem of climate change is building on distinct observations that are in turn fundamentally bound to specific instruments, organizations and, more generally, a historically contingent problem-infrastructure.

References:

Arrhenius, S. (1896). XXXI. On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air Upon the Temperature of the Ground. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 41(251), 237–276.

Ekholm, N. (1901). On the Variations of the Climate of the Geological and Historical Past and Their Causes. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 27(117), 1–62.

Fleming, J. R. (1998). Historical perspectives on climate change. Oxford University Press.

Hulme, M. (2014). Can Science Fix Climate Change? A Case Against Climate Engineering.

Parker, G. (2013). Global crisis: war, climate change and catastrophe in the seventeenth century. New Haven: Yale University Press.