by Steve Vanderheiden, CSTPR Core Faculty Member

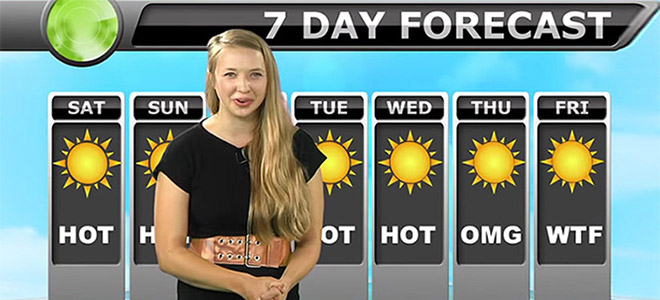

The first two months of 2017 have brought good and bad news regarding United States efforts to control greenhouse gas emissions, illustrating an evolving relationship between science and policy in domestic climate change governance that portents some heightened future conflicts but also new points of potential convergence and consensus over mitigation actions.

Of course, changes in the executive branch have garnered the most attention, signaling an increasing reluctance to use federal powers to reduce greenhouse gases, along with decreasing reliance upon and support for policy-relevant science. President Trump, who cast climate change as a “hoax” and promised to “cancel” the Paris Agreement while on the campaign trail, maintained this hostile posture toward science-based policy by appointing climate skeptics Myron Ebell to head the EPA’s transition and Scott Pruitt as EPA Administrator. Pruitt, in turn, has begun to staff the agency with harsh critics of climate science and environmental regulation in Ryan Jackson and Byron Brown, prompting Coral Davenport to observe that “Mr. Pruitt seems intent on building an E.P.A. leadership that is fundamentally at odds with the career officials, scientists and employees who carry out the agency’s missions (Davenport 2017a).”

Within the past week alone, president Trump has issued executive orders to Pruitt to begin the process of dismantling the two Obama administration programs that promise to control CO2 emissions in the Clean Power Plan and automobile fuel economy requirements, and threatened to challenge California’s pioneering climate policy efforts by cancelling the regulatory waiver that allows it to impose more demanding automobile air pollution standards than are mandated under federal law. Following on the heels of gag orders against EPA and other government scientists, revisions to agency websites to remove links to scientific reports and references to “science-based” pollution control standards, concerns about scrubbing critical scientific research data and budget proposals to slash staffing at EPA and NOAA, this week’s new orders contribute toward general expectations for an administration bent on rollback of regulatory standards and undermining the capacity of executive agencies for making science-based policy (Harmon 2017).

Lost amidst the rising alarm about threats to scientific research data or capacity and diminished role for science in climate policy, however, were several glimpses that suggest momentum shifting in the opposite direction than is on display in electoral or political fortunes. Pruitt, in January testimony to Congress prior to his confirmation, rejected his own as well as his boss’s rhetoric about climate science being a hoax, acknowledging that human activities contribute “in some manner” to climate change. While his actions suggest hostility to climate policy efforts, and he would later question whether this anthropogenic contribution to climate change came through CO2 emissions, this apparent rhetorical shift in a key science policy stance central to his agency’s mission portents a delegitimation of climate skepticism, even among ideologically and politically hostile officials (Davenport 2017b). Resistance to mitigation imperatives is more difficult on economic or ethical grounds than through the denial of impacts or anthropogenic causes, making Pruitt’s acknowledgement significant for narrowing science policy discourses to conflict over issues more favorable to the kind of meaningful action that his appointments and policy decisions actively resist. Insofar as US neoliberal antiregulatory politics has largely relied upon climate skepticism to unify its political coalitions and justify its policy actions, this discursive shift away from outright skepticism and toward economic or geopolitical considerations to maintain such coalitions, their splintering or a realignment among mitigation action opponents may presage the waning power of organized opposition to regulatory climate policy action (Antonio and Brulle 2011).

Additionally, perceived threats against science positions in executive agencies, funding for future scientific research, and concerns about the accessibility and integrity of scientific data have led to an upswing of science policy advocacy, from new initiatives like the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative in making data more secure and accessible to the political mobilization of scientists and pro-science groups to advocate for the interests of scientific research and science-based policy, to efforts at recruitment of scientists to run for public office and to call attention to threats against the scientific enterprise. While the threats responsible for this mobilization are real and concerning, they also assisted in overcoming the inertia against more effective forms of political mobilization and have begun to counteract entrenched apolitical norms in many science disciplines. Such actions could help to stem the tide against science-based policy in the short term as well as allowing for more effective advocacy in the long run as defensively politicized persons and groups remain mobilized after current threats have passed.

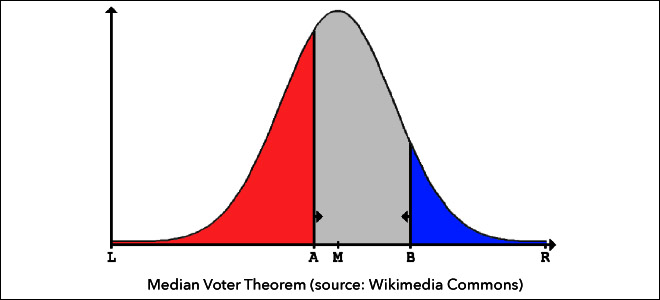

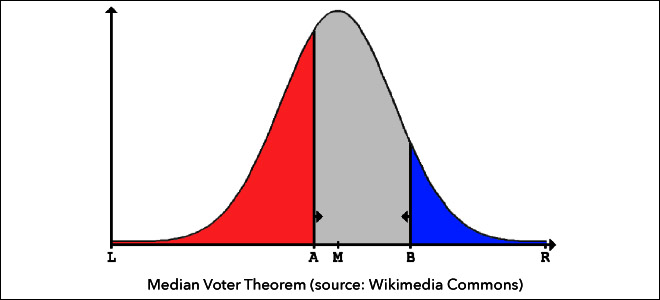

Finally, the February release of a carbon tax proposal by several senior GOP establishment figures, led by James Baker, George Schultz and Henry Paulson, illustrates the potential for coalition-building between center-right pragmatists and progressive environmentalists around carbon pricing. Spatial voting models (see below) illustrate new opportunities for consensus around solutions that appeal to moderates alienated by further shifts to the right by Congress and the new administration, where opportunities for bipartisanship around effective climate policies have up to now been elusive. Electoral motives to remain closer to the median voter could provide incentives to break with increasingly polarized Congressional party leadership, and members from purple states like Colorado seek to balance their ideological affinities and campaign finance loyalties with electoral realities. Given the need under administrative law to replace rather than simply repealing the Clean Power Plan, such a proposal provides political cover for members seeking to deny Obama credit for reducing power plant emissions while utilizing enough market logic to appeal to party economic orthodoxy. Despite the short-term ascendancy of clearly hostile opponents of any form of climate policy action, the US may be closer to a viable majority coalition is support of national carbon pricing that it has ever been.

One must not be too sanguine about openings for future coalition-building and opportunities for future progress in science policy domains like those around climate change mitigation, for their recent appearance owes to the seriousness of the pernicious threat to which they are responses. Nonetheless, political science counsels an alternative formulation of Newton’s Law: that political actions are often accompanied by equal and opposite reactions, and threats to science-based policy appear to have generated several new and potentially important sources of advocacy or reductions in previously entrenched obstacles to cooperation on its behalf.

Antonio, Robert J. and Robert J. Brulle (2011). “The Unbearable Lightness of Politics: Climate Change Denial and Political Polarization,” Sociological Quarterly 52(2): 195-202.

Davenport, Coral (2017a). “E.P.A. Head Stacks Agency With Climate Change Skeptics,” The New York Times (online edition), 7 March 2017.

Davenport, Coral (2017b). “E.P.A. Chief Doubts Consensus View of Climate Change,” The New York Times (online edition), 9 Match 2017.

Harmon, Amy (2017). “Activists Rush to Save Government Science Data — If They Can Find It,” The New York Times (online edition), 6 March 2017.

Want to Buy a New Stove?

by Katie Dickinson, CSTPR Core Faculty Member

For most of you reading this, the technologies you used to cook your last meal were probably fairly clean. Meeting your daily cooking needs does not expose you to harmful levels of household air pollution. But for nearly half of the world’s population, cooking and smoke exposure go hand in hand. Nearly three billion people worldwide rely on stoves that burn biomass, like wood and charcoal. Not eating is not an option, but exposure to household air pollution linked to these cooking practices can be deadly: nearly 4 million people die prematurely from diseases linked to smoke from cooking.

Photo: Ghanaian woman stirs rice cooked over improved woodstoves during “Prices, Peers, and Perceptions (P3)” project stove demonstration and marketing meeting.

Looking at the problem from this angle, it’s difficult to understand why people would choose to continue to cook over open fires and other polluting biomass stoves. But a little more reflection might remind you that changing behavior and adopting new practices is hard for all of us, for a multitude of reasons, and that many potential barriers exist to spreading the adoption of even the most promising new practices and technologies.

What if I told you that the stove you were using was bad for your family’s health, and that from now on you should only cook using a fancy new gadget that used some sort of specially designed fuel capsules? I imagine you’d have a few questions before you’d rush out to buy one of these “improved” stoves:

These and other questions are currently facing households in Northern Ghana who are participating in the Prices, Peers, and Perceptions (P3) improved cookstove study. Since 2013, I’ve been working with colleagues at CU Boulder, NCAR, and the Navrongo Health Research Center in Ghana, to better understand how use of cleaner stoves could be scaled up in this region. This year, our interdisciplinary, international research team has partnered with a small Ghanaian NGO, the Organization for Indigenous Initiatives and Sustainability (ORGIIS), to implement a new set of interventions offering households different types of improved cookstoves at different prices.

In March, ORGIIS began the first set of interventions with study participants from the rural areas of our study region, the Kassena-Nankana Districts on Ghana’s northern border. ORGIIS holds small meetings in rural communities, inviting six households at a time to come and try out two different types of improved woodstoves, which use the same fuels households are used to but should produce less smoke. After the meeting, each participant is given an option to buy up to two stoves of either type. Because we are interested in learning about households’ willingness to pay for these stoves, the prices are randomized across different groups. In some meetings, households can get the stoves for free, while in other communities, participants must pay lower or higher prices for their stoves, though all households get a substantial discount over the stoves’ market price. (The full price of the more basic stove, called the Greenway Jumbo, is about $33, while the fancier ACE1 stove, which also includes a USB charging port and a small LED light, costs about $75.)

In this video, you can see ORGIIS and NHRC staff demonstrating these two stoves to study participants at a community meeting.

The other factor we are exploring is whether having social contacts that have experience with these stoves makes participants more or less likely to buy them. About half of our 300 rural P3 participants are from communities that were included in our earlier REACCTING cookstove study, which involved free distribution of similar stoves, while the other half are from different communities without much exposure to these stoves. We’ll be comparing stove purchasing and stove use choices for these “peer” and “non-peer” groups, and seeing how both prices and peers’ experience affect perceptions of these new stoves and their quality.

The rural intervention meetings will wrap up in April, and our team will visit Navrongo in May to plan an additional set of interventions that will offer liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) stoves to participants in the more urban central area of the study districts. While the challenge of cleaner cooking won’t be solved overnight, we hope that learning more about the factors that influence households’ choices will help point the way towards cleaner home environments and healthier communities.