Houston Chronicle

March 28, 2018

by James Osborne

Social media feeds on Tuesday morning sported links to an article listing the “Nine Reasons Why Patagonia Secretly Loves Fracking,” and memes including a picture of empty shelves with the caption, “Patagonia introduces new petroleum-free product line.”

The online campaign against the outdoor gear manufacturer was the work of a group called Texans for Natural Gas, a “grassroots” organization funded by oil and gas companies including EnerVest, EOG Resources and XTO Energy, a division of Exxon Mobil, which said in a press release it was taking issue with Patagonia’s “hypocritical” opposition to fracking.

As the fight over fracking and climate change has ramped up in recent years, oil and gas companies are engaged in increasingly creative public relations campaigns to convince the American public that transitioning away from petroleum products represents a foolish and calamitous mistake.

If the articles blasted out across the Internet on Tuesday morning all sounded a little ridiculous, that was exactly the point, says Steve Everley, the oil and gas consultant who serves as a spokesman for Texans for Natural Gas.

“There’s a broader conversation now with a company like Patagonia that uses petroleum products and then plants their principled flag in the ground,” he said. “This is intended to be funny and a little cheesy, and help people laugh a little. Everything these days seems to be the sky is falling, but every single day the sky is still there.”

Patagonia executives declined comment on the effort.

How the California-based company ended up the target of an oil industry-backed attack campaign traces back to Patagonia’s longtime criticism of the hydraulic fracturing boom. In 2013 then CEO Casey Sheahan wrote to California legislators, “We believe the damage caused by this process to human health and to the environment, especially the air, soil and water quality, will have consequences that can’t be undone for centuries.”

The tense relationship with the oil industry only intensified in December when Patagonia sued the U.S. government to block President Donald Trump from reducing the size of the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments.

The homepage of the company’s website that day read, “The President stole your land.”

Attacking climate scientists

Now environmentalists see the attack against Patagonia as an effort to sow confusion while discrediting a well-known and well-financed critic of the Trump administration’s environmental policies — Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard’s net worth was pegged at $1 billion by Forbes last year.

Climate scientists like Michael Mann of Penn State University and Katharine Hayhoe of Texas Texas University have been the subject of similar attacks.

Naomi Oreskes, a professor at Harvard University who co-wrote “Merchants of Doubt” about the oil industry’s efforts to undermine climate science, said the attack against Patagonia reflected the latest in a long running campaign by some corners of the oil and gas industry to slow the movement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“They recycle different arguments based on what they think will work in any given moment,” she said. “They say were all hypocrites because we drive a car. … Look, we’re in a system and all of us are part of it. That’s why we’re trying to change the system.”

In recent years, the oil and gas industry, which was long famous for maintaining a steely silence in the public sphere, has become increasingly visible.

Last year, the American Petroleum Institute, the industry’s largest lobbying organization, ran an ad during the Super Bowl with images of products from makeup to artificial limbs, telling viewers, “This ain’t your daddy’s oil.”

Everley said he, along with an Austin public relations firm, launched the website FrackFeed.com — where the Patagonia article posted Tuesday — in 2015 as a way to reach out to millennials who weren’t reading the industry’s policy papers.

“It was designed to reach a younger audience through memes and listicles,” he said. “There was a legitimate concern what the industry was putting out was not reaching younger people.”

Gaining followers

So far they seem to be having some success. Facebook shows Texans for Natural Gas having more than 250,000 followers, while FrackFeed counts over 130,000 followers.

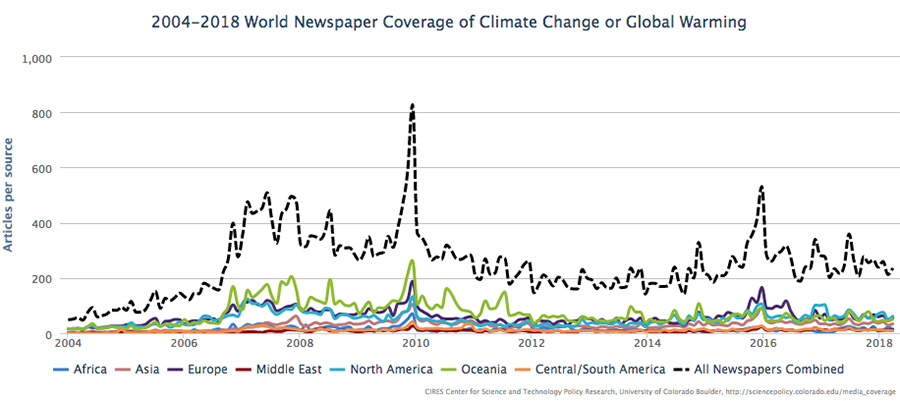

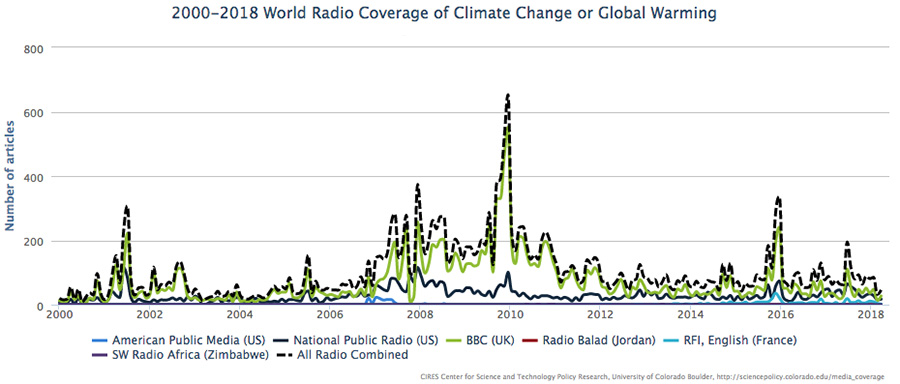

At the same time, a recent study by the University of Colorado and Yale University found that climate change denial groups, many linked to the oil and gas industry, were getting increasing coverage in print and television news.

“These front groups are getting a little more engaged in the public conversations and media attention is picking up on them,” said Max Boykoff, director of the Center for Science and Technology Policy Research at the University of Colorado. “It is less clear why that is the case.”

In recent years, some oil companies, like BP and Shell, have become increasingly vocal about the need to shift away from oil to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, predicting oil demand could peak within a matter of two decades.

But within some oil companies, the fight is far from over, said John Hanger, a former top environmental official in Pennsylvania who has been critical of some environmentalist claims about fracking’s danger.

“The oil industry is diverse, but there are some really reactionary, dinosaur-like parts of the industry,” he said. “I doubt Shell or BP wants to be anywhere near that campaign” against Patagonia.

CSTPR’s Fulbright Visiting Scholar: Anna Kukkonen

by Abigail Ahlert, CSTPR Science Writing Intern

Last semester, Anna Kukkonen had a quintessential “Boulder” experience. A friendly man waiting next to her at a bus stop asked what she worked on. When she explained her research on climate change debates in the media, the man mentioned that he was a part of the Shanahan Ridge Neighbors for Climate Action—a South Boulder group that discusses local sustainability issues—and invited her to join. She was delighted by the coincidence. Boulder is a hub for those interested in the environment, and as a Fulbright visiting scholar at University of Colorado’s Center for Science and Technology Policy (CSTPR), Kukkonen is truly finding opportunities around every corner.

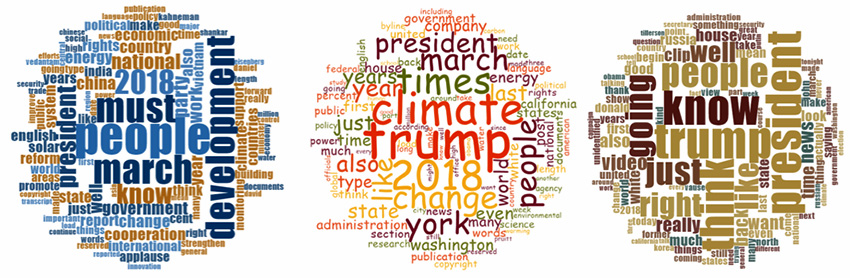

Kukkonen is a PhD student in Sociology at the University of Helsinki, and applied for a Fulbright grant with CU’s high ranking environmental policy program in mind. She anticipated that visiting CU would provide many opportunities for collaboration, particularly since her research is well-aligned with that of Dr. Max Boykoff, Director of CSTPR. In 2017, Kukkonen and her co-authors published a paper applying the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) theory to U.S. media coverage of climate change from 2007-2008. According to Kukkonen, “The general beliefs concerning the reality of anthropogenic climate change, the importance of ecology over economy and desirability of governmental regulation divide organizations into three advocacy coalitions: the economy, ecology and science coalitions”. Specific beliefs concerning policy instruments such as cap and trade and alternative energy do not. She found that the ACF theory could be clarified to better account for how beliefs contribute to coalition formation in specific points in time and policy domains.

During her time in Boulder, Kukkonen is working on multiple projects involving climate change politics. First, she is comparing media discussions of climate change in the United States, Canada, Brazil, India and Finland. Kukkonen works with researchers from these countries and others in the Comparing Climate Change Policy Networks (COMPON) project. She finds writing with international colleagues to be very rewarding and acknowledges that the writing process is the most challenging part of her work. “You really grow as a person when you do this kind of stuff, and you learn to take critique,” she says. Additionally, Kukkonen is studying the roles of different types of policy actors (such as non-profit organizations, universities and businesses) and the moral justifications they use in the Finnish and Canadian media debates on Arctic climate change.

When she isn’t working on her PhD research, Kukkonen attends classes offered by CU’s Environmental Studies Program, where she has learned more about the interactions between science and policy. To her surprise, many of her classmates are natural scientists. “It has been very enlightening how differently we think,” she says. “They have their own conception of what social science is and that has been very interesting.” Discussions with her classmates have challenged her to describe her work and its use to researchers outside of her field, and this has given her greater confidence in her role as a social scientist.

Kukkonen also appreciates how many scientists at the University of Colorado prioritize communicating their results with the public. “This is another reason why I came to CSTPR, because here I think they focus a lot on how researchers can communicate their research to the general audience. I notice that people in the US like to talk about their research in a way that people who are not experts in that field can understand it,” she says. In May, Kukkonen will return to Finland to complete her PhD. She is excited about the direction her research has taken at CSTPR and hopes to continue studying climate change after graduate school. “Now I find purpose in my research better than before I came here,” she says. “I feel more motivated after this experience because I’ve had to think about my research in a more practical way.”