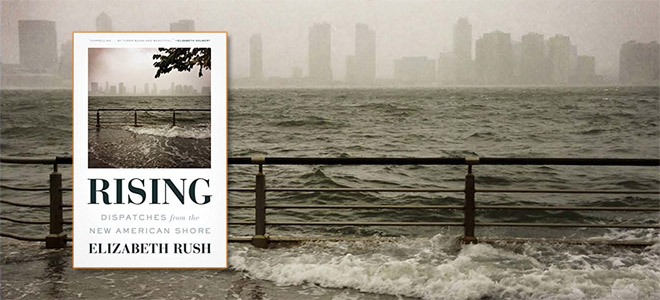

National Geographic, August 2018

by Eve-Lyn S. Hinckley

CSTPR Faculty Affiliate, National Geographic Explorer and Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, University of Colorado Boulder

The American Cordillera is a jigsaw of mountain ranges that curls southward from the Alaskan coast through my home range, the Colorado Rocky Mountains, to its end in the Antarctic Peninsula. I’m making my first stop along its length – coastal British Columbia – to start a new project studying the rain chemistry of remote regions.

I travel with my collaborator, Sheila Murphy, a research hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Together, we seek to determine whether the chemical signature of human development moves in rainwater to the wilds of BC, the US, Ecuador, and Patagonia. With the exception of the US site, all are locations of National Geographic Unique Lodges of the World, our partners in this effort.

As each flight connection takes us farther from Denver and closer to the BC coast, the aircraft get smaller and smaller. When we reach Port Hardy, we walk down a quiet dock to a three-seater floatplane. It is a tiny bird, like a lone tern, perched at the end of the dock. Travel by such a bird is a first for me.

The pilot instructs us to crank open the metal doors and demonstrates how to bust out the windows in case of emergency. We hop in, my hands shaking as I buckle my lap belt. He fires the motor and we are off, the plane’s narrow limbs lifting us above the water.

The BC coast stretches before us, fingers of the Great Bear Rainforest stroking Queen Charlotte Strait. Still, gray sky surrounds us as we buzz along our watery path northeast toward Nimmo Bay. There, a small wilderness resort floats on narrow docks between water and land. No roads lead to Nimmo—hence the floatplane.

“See many whales this time of year?” I yell at the pilot. But the propeller is loud and the motor drowns my voice. I take a video of the blades clipping the air for my kids, rain streaking the tiny windshield.

We’re not disappointed by the weather – we’ve come for rain. More precious is the nitrogen dissolved within its droplets: a fundamental nutrient that sustains life. Here, that means plankton, salmon, grizzly bears.

Nitrogen is one of the elements most manipulated by humans. In the absence of our engineering, the vast atmospheric pool of nitrogen gas is accessible only to specialized bacteria. They have the capacity to transform this gas into available forms that can be used by plants and animals for growth.

But the Industrial Revolution ushered in a whole new era. Our move toward dependence on fossil fuels, combined with work by a team of chemists who figured out how to synthesize fertilizers, changed the world. The latter development, known as the Haber-Bosch process, created industrial nitrogen fertilizers, which enabled us to grow crops intensively. No longer were we dependent on the slow, small efforts of bacteria. This boon allowed our human population to grow. The combined effects of fossil fuels combustion, conversion of forested land for agriculture, and use of nitrogen fertilizers have more than doubled the amount of nitrogen cycling through air, land, and water systems, polluting them in many places around the world.

Yet you can almost forget all of this in the wilds of BC. This landscape is new to Sheila and me. We typically study places where people and their influences are immediate – agricultural areas, urban centers, wildfire scars. We share a drive to understand how people change the water and nutrient cycles that support life on Earth, and to work with land managers to balance the goals of a developed world and sustaining the health of people and ecosystems.

This project is different. Like the guests who come to Nimmo Bay’s wilderness resort, we’re drawn to its location, far from the noise and haze of our usual research sites. Sheila and I will use the tools in our laboratories back in Boulder, Colorado, to measure the levels of nitrogen in rain, capitalizing on the distinct chemical signature of human-derived nitrogen to determine whether it reaches the BC coastal range. Rain can carry excess nitrogen far distances, even to those places we still think of as wild, pristine.

The plane touches down and I take a breath, tell the pilot he made it look easy. “It was,” he laughs and guides the plane to the dock. My hands are no longer shaking as I unbuckle my lap belt and step off.

Members of the Nimmo Bay staff greet us: someone holds an umbrella over my head and offers me a warm, wet towel to wipe my face and hands. I smile and shake hands, slightly flustered. It is a new way to start to a field project with a welcoming committee, not to mention the floatplane ride.

We are anxious to connect with our research equipment, which made the journey before we did. Dylan, one of the wilderness guides, shows us the four stamped boxes we mailed weeks ago, and we begin unpacking. Funnels studded with cable ties to discourage birds from perching, sections of PVC and rebar to mount the funnels above the ground surface, and precious tubes filled with resins that will collect nitrogen from the rainwater falling into the funnels. We account for all parts of our rain collectors and get ready to distribute them across the landscape.

Salmon remains left by a grizzly near Nimmo Bay Resort.

Adrien, head of the guide team, says that he and Dylan can take us to scout study sites by boat for the afternoon. The guide team is almost exclusively tall, dark-haired men dressed in the emerald greens and blues of the landscape where they were born. Many found their way to Nimmo Bay after tours through the commercial fishing industry. We learn that the move from resources extraction to guiding was welcome.

We will rely on the guides for the duration of our two-year project. They will record rainfall data, collect stream water, and swap out and mail the nitrogen-filled resin tubes every two months until the lodge closes for winter. Their efforts are critical; without the commitment of the guides, there will be no data.

“This is where the grizzlies will be pulling salmon from the river onto the banks,” Adrien tells us. We’re standing in a mossy grove along a quiet river. It’s hard to believe that it will soon be a raucous feeding frenzy when the bears journey down from the mountains and salmon swim from ocean to river, the two groups meeting in the middle. The pearly remains of last year’s run provide definitive evidence—jaws and fin plates left in piles on the ground.

Adrien not only manages the guide staff, but also monitors the bears’ movements closely. He’s part of a conservation effort to keep their population healthy and raise awareness of their vulnerability within the Great Bear Rainforest. I can’t help but look around us at the evidence of feedings past and convert the wreckage into a nitrogen flux, imagining how salmon carnage enriches the soil each summer. I consider the next set of measurements I’d like to make.

Sheila and I decide to place the collectors under three different environments typical of the Great Bear Rainforest– open sky, old growth cedars, and secondary growth hemlock trees—to determine whether they have different nitrogen inputs. We are confident that we can repeat this design at our other sites, comparing open and closed canopies.

Dylan’s on grizzly watch while we pound in rebar and screw funnels to resin tubes, our eyes either on the ground or reading the trees. We are learning the landscape as we install collectors in nests of four, filling in the details we simply could not know from offices two thousand miles away.

Our cabin sits by the waterfall that inspired Nimmo Bay Resort’s construction in the 1970s. When we’re not out with the guides, we’re in researcher mode, reading and writing. Sheila is transfixed on her laptop screen, determined to pull what little data exist for the vast rugged landscape we’ve now entered.

Her scavenger hunt reveals that the nearest record of rainfall near the region was in Kingcome Inlet, about 30 kilometers east of Nimmo Bay, as the gull flies. The data she finds are for the mid-1970s to 1980s. Rain and snow amounts probably vary regionally, but the data provide a ballpark figure for the average annual rainfall amount, 2.5 meters. This information is better than nothing…and confirmation that our project will make a contribution.

We install a simple, manual rain gauge near the guide shack. Everyone is excited about it. The guides tell us that they will read it daily, beginning a new era of rain data collection at Nimmo Bay. We will match the rainfall amounts with the chemistry data from our collectors, allowing us to quantify the flux of nitrogen coming into the region. Rainfall amount and chemical concentration go hand in hand to understand one of Earth’s most important nutrient cycles.

Before Sheila and I leave Nimmo Bay, we brief the guides one last time and record the first rain gauge reading, officially beginning our study. We pile into the Raven – purportedly the fastest boat north of Seattle – with six other staff members who are rotating off work for a couple of weeks.

“Can you believe that our next stop’s in a week?” I say to Sheila, thinking ahead to Ecuador, when we will continue our journey. “Cloud forest!” She smiles and we take our seats.

Dylan is at the helm and we motor away, slowly at first, as though reluctant to head back to civilization. I feel a sense of calm, knowing that our first set of collectors is installed, already receiving drops of rain whose nitrogen content we will determine in a couple of months.

What secrets will we learn about this place? It’s one of the great questions we get to ask every time we start a new project.

Sitting back, we watch the waterside cabins get smaller and smaller, until they are just six red and white dots against the black water. Then we round a bend and Nimmo Bay is gone from view, swallowed back into the wild.

As was noted at the top, considerable attention was paid to political content of coverage during the month of August. Frequent stories from the Southern Hemisphere involved the replacement of Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull with Scott Morrison. While Morrison was invoked 571 times across 495 articles in August, the focus was on the departure of Prime Minister Turnbull, mentioned 2311 times in the month. Stories like ‘Energy industry anger as PM splits climate from power policy’ by journalists Ben Packham and Greg Brown in

As was noted at the top, considerable attention was paid to political content of coverage during the month of August. Frequent stories from the Southern Hemisphere involved the replacement of Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull with Scott Morrison. While Morrison was invoked 571 times across 495 articles in August, the focus was on the departure of Prime Minister Turnbull, mentioned 2311 times in the month. Stories like ‘Energy industry anger as PM splits climate from power policy’ by journalists Ben Packham and Greg Brown in

Into the Wild – For Rain | Part I. British Columbia

National Geographic, August 2018

by Eve-Lyn S. Hinckley

CSTPR Faculty Affiliate, National Geographic Explorer and Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, University of Colorado Boulder

The American Cordillera is a jigsaw of mountain ranges that curls southward from the Alaskan coast through my home range, the Colorado Rocky Mountains, to its end in the Antarctic Peninsula. I’m making my first stop along its length – coastal British Columbia – to start a new project studying the rain chemistry of remote regions.

I travel with my collaborator, Sheila Murphy, a research hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Together, we seek to determine whether the chemical signature of human development moves in rainwater to the wilds of BC, the US, Ecuador, and Patagonia. With the exception of the US site, all are locations of National Geographic Unique Lodges of the World, our partners in this effort.

As each flight connection takes us farther from Denver and closer to the BC coast, the aircraft get smaller and smaller. When we reach Port Hardy, we walk down a quiet dock to a three-seater floatplane. It is a tiny bird, like a lone tern, perched at the end of the dock. Travel by such a bird is a first for me.

The pilot instructs us to crank open the metal doors and demonstrates how to bust out the windows in case of emergency. We hop in, my hands shaking as I buckle my lap belt. He fires the motor and we are off, the plane’s narrow limbs lifting us above the water.

The BC coast stretches before us, fingers of the Great Bear Rainforest stroking Queen Charlotte Strait. Still, gray sky surrounds us as we buzz along our watery path northeast toward Nimmo Bay. There, a small wilderness resort floats on narrow docks between water and land. No roads lead to Nimmo—hence the floatplane.

“See many whales this time of year?” I yell at the pilot. But the propeller is loud and the motor drowns my voice. I take a video of the blades clipping the air for my kids, rain streaking the tiny windshield.

We’re not disappointed by the weather – we’ve come for rain. More precious is the nitrogen dissolved within its droplets: a fundamental nutrient that sustains life. Here, that means plankton, salmon, grizzly bears.

Nitrogen is one of the elements most manipulated by humans. In the absence of our engineering, the vast atmospheric pool of nitrogen gas is accessible only to specialized bacteria. They have the capacity to transform this gas into available forms that can be used by plants and animals for growth.

But the Industrial Revolution ushered in a whole new era. Our move toward dependence on fossil fuels, combined with work by a team of chemists who figured out how to synthesize fertilizers, changed the world. The latter development, known as the Haber-Bosch process, created industrial nitrogen fertilizers, which enabled us to grow crops intensively. No longer were we dependent on the slow, small efforts of bacteria. This boon allowed our human population to grow. The combined effects of fossil fuels combustion, conversion of forested land for agriculture, and use of nitrogen fertilizers have more than doubled the amount of nitrogen cycling through air, land, and water systems, polluting them in many places around the world.

Yet you can almost forget all of this in the wilds of BC. This landscape is new to Sheila and me. We typically study places where people and their influences are immediate – agricultural areas, urban centers, wildfire scars. We share a drive to understand how people change the water and nutrient cycles that support life on Earth, and to work with land managers to balance the goals of a developed world and sustaining the health of people and ecosystems.

This project is different. Like the guests who come to Nimmo Bay’s wilderness resort, we’re drawn to its location, far from the noise and haze of our usual research sites. Sheila and I will use the tools in our laboratories back in Boulder, Colorado, to measure the levels of nitrogen in rain, capitalizing on the distinct chemical signature of human-derived nitrogen to determine whether it reaches the BC coastal range. Rain can carry excess nitrogen far distances, even to those places we still think of as wild, pristine.

The plane touches down and I take a breath, tell the pilot he made it look easy. “It was,” he laughs and guides the plane to the dock. My hands are no longer shaking as I unbuckle my lap belt and step off.

Members of the Nimmo Bay staff greet us: someone holds an umbrella over my head and offers me a warm, wet towel to wipe my face and hands. I smile and shake hands, slightly flustered. It is a new way to start to a field project with a welcoming committee, not to mention the floatplane ride.

We are anxious to connect with our research equipment, which made the journey before we did. Dylan, one of the wilderness guides, shows us the four stamped boxes we mailed weeks ago, and we begin unpacking. Funnels studded with cable ties to discourage birds from perching, sections of PVC and rebar to mount the funnels above the ground surface, and precious tubes filled with resins that will collect nitrogen from the rainwater falling into the funnels. We account for all parts of our rain collectors and get ready to distribute them across the landscape.

Salmon remains left by a grizzly near Nimmo Bay Resort.

Adrien, head of the guide team, says that he and Dylan can take us to scout study sites by boat for the afternoon. The guide team is almost exclusively tall, dark-haired men dressed in the emerald greens and blues of the landscape where they were born. Many found their way to Nimmo Bay after tours through the commercial fishing industry. We learn that the move from resources extraction to guiding was welcome.

We will rely on the guides for the duration of our two-year project. They will record rainfall data, collect stream water, and swap out and mail the nitrogen-filled resin tubes every two months until the lodge closes for winter. Their efforts are critical; without the commitment of the guides, there will be no data.

“This is where the grizzlies will be pulling salmon from the river onto the banks,” Adrien tells us. We’re standing in a mossy grove along a quiet river. It’s hard to believe that it will soon be a raucous feeding frenzy when the bears journey down from the mountains and salmon swim from ocean to river, the two groups meeting in the middle. The pearly remains of last year’s run provide definitive evidence—jaws and fin plates left in piles on the ground.

Adrien not only manages the guide staff, but also monitors the bears’ movements closely. He’s part of a conservation effort to keep their population healthy and raise awareness of their vulnerability within the Great Bear Rainforest. I can’t help but look around us at the evidence of feedings past and convert the wreckage into a nitrogen flux, imagining how salmon carnage enriches the soil each summer. I consider the next set of measurements I’d like to make.

Sheila and I decide to place the collectors under three different environments typical of the Great Bear Rainforest– open sky, old growth cedars, and secondary growth hemlock trees—to determine whether they have different nitrogen inputs. We are confident that we can repeat this design at our other sites, comparing open and closed canopies.

Dylan’s on grizzly watch while we pound in rebar and screw funnels to resin tubes, our eyes either on the ground or reading the trees. We are learning the landscape as we install collectors in nests of four, filling in the details we simply could not know from offices two thousand miles away.

Our cabin sits by the waterfall that inspired Nimmo Bay Resort’s construction in the 1970s. When we’re not out with the guides, we’re in researcher mode, reading and writing. Sheila is transfixed on her laptop screen, determined to pull what little data exist for the vast rugged landscape we’ve now entered.

Her scavenger hunt reveals that the nearest record of rainfall near the region was in Kingcome Inlet, about 30 kilometers east of Nimmo Bay, as the gull flies. The data she finds are for the mid-1970s to 1980s. Rain and snow amounts probably vary regionally, but the data provide a ballpark figure for the average annual rainfall amount, 2.5 meters. This information is better than nothing…and confirmation that our project will make a contribution.

We install a simple, manual rain gauge near the guide shack. Everyone is excited about it. The guides tell us that they will read it daily, beginning a new era of rain data collection at Nimmo Bay. We will match the rainfall amounts with the chemistry data from our collectors, allowing us to quantify the flux of nitrogen coming into the region. Rainfall amount and chemical concentration go hand in hand to understand one of Earth’s most important nutrient cycles.

Before Sheila and I leave Nimmo Bay, we brief the guides one last time and record the first rain gauge reading, officially beginning our study. We pile into the Raven – purportedly the fastest boat north of Seattle – with six other staff members who are rotating off work for a couple of weeks.

“Can you believe that our next stop’s in a week?” I say to Sheila, thinking ahead to Ecuador, when we will continue our journey. “Cloud forest!” She smiles and we take our seats.

Dylan is at the helm and we motor away, slowly at first, as though reluctant to head back to civilization. I feel a sense of calm, knowing that our first set of collectors is installed, already receiving drops of rain whose nitrogen content we will determine in a couple of months.

What secrets will we learn about this place? It’s one of the great questions we get to ask every time we start a new project.

Sitting back, we watch the waterside cabins get smaller and smaller, until they are just six red and white dots against the black water. Then we round a bend and Nimmo Bay is gone from view, swallowed back into the wild.