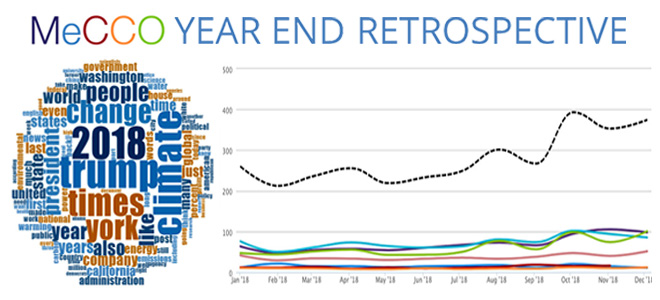

Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO)

January 2019 Summary

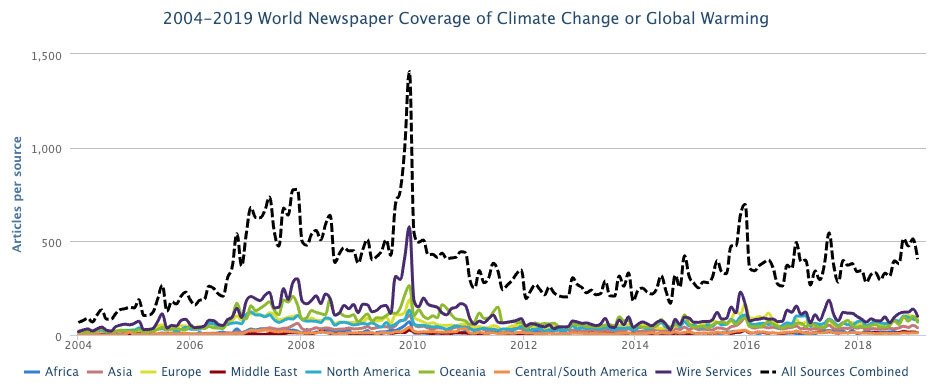

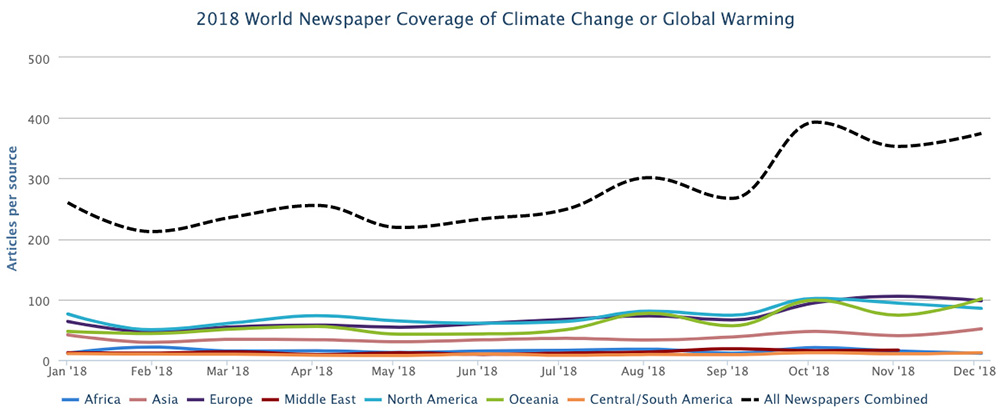

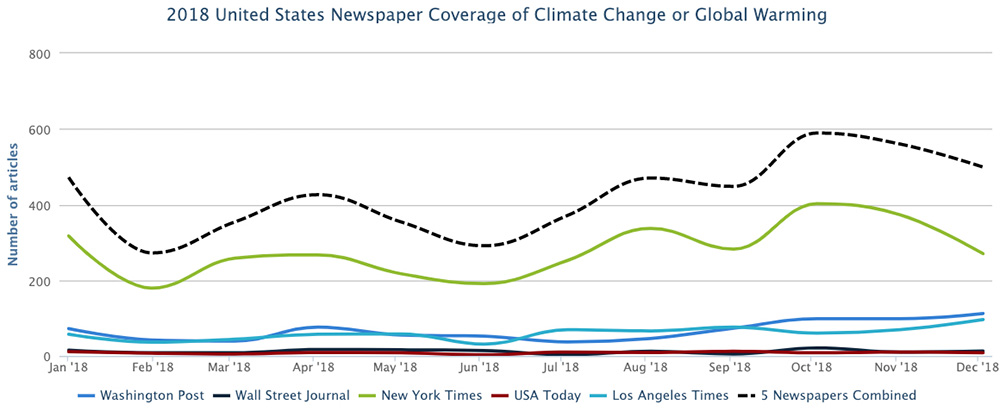

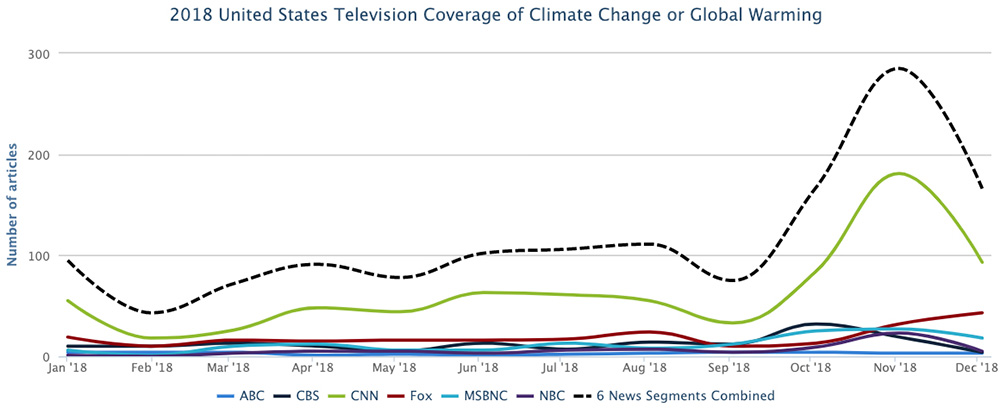

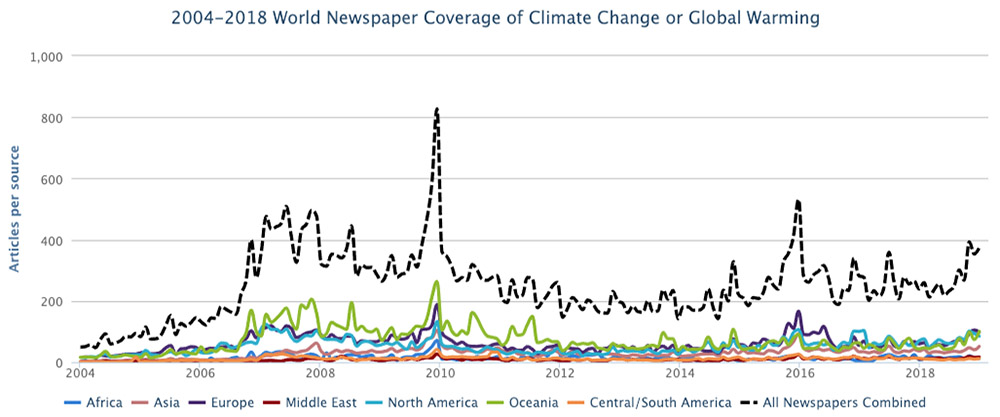

January media attention to climate change and global warming was down 20% throughout the world from the previous month of December 2018, but up just over 15% from January 2018.

While African coverage was up 21% from the previous month, it was down in all other regions, including North America where coverage was down 10% in January compared to the previous month of December 2018.

Figure 1 shows increases and decreases in newspaper media coverage at the global scale – organized into seven geographical regions around the world – over the past 181 months (from January 2004 through January 2019).

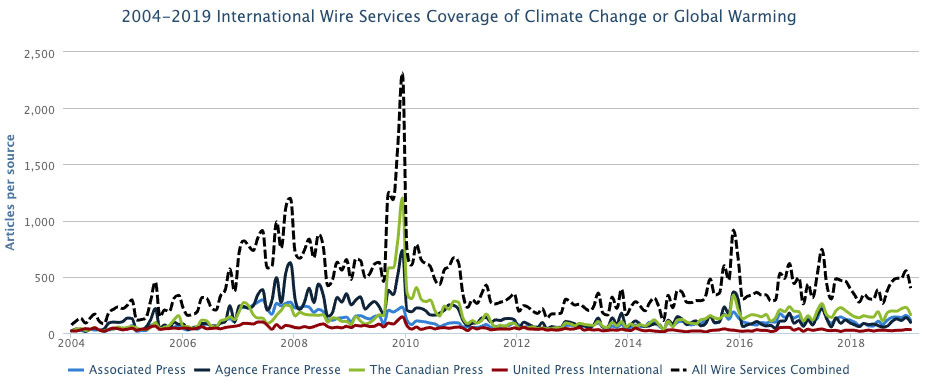

This month we introduce media monitoring of Public Broadcasting Services on United States television and additional monitoring across four wire services: The Associated Press, Agence France Press (AFP), The Canadian Press, and United Press International (UPI). We at the Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) now monitor sixty-six newspaper sources, six radio sources and seven television sources spanning thirty-nine countries with segments and articles in English, Spanish, German and Portuguese. In addition to English-language searches of ‘climate change’ or ‘global warming’, we now conduct searches of Spanish-language sources through the terms ‘cambio climático’ or ‘calentamiento global’, and commenced with searches of German-language sources through the terms ‘klimawandel’ or ‘globale erwärmung’ as well as Portuguese-language sources through the terms ‘mudanças climáticas’ or ‘aquecimento global’.

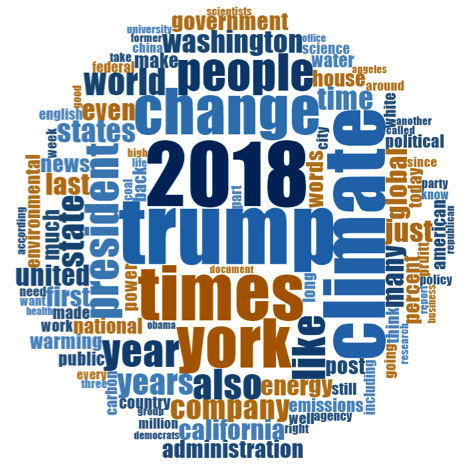

Moving to considerations of content within these searches, Figure 3 shows word frequency data in Indian newspaper media coverage in January 2019.

In January, considerable attention was paid to political and economic content of coverage. Prominently, the movements of newly elected Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro captured media attention. From his inauguration in January, coverage focused on his efforts to commodify ecosystem services in the country. For example, Bolsonaro immediately sought to cede control of indigenous lands to agribusiness. Journalist Marina Lopes from The Washington Post reported that “Brazil’s new right-wing president opened the door Wednesday for more potential development and tree-clearing in the Amazon rain forest, giving the Agriculture Ministry oversight over which lands are granted protected status. The move by Jair Bolsonaro — in one of his first acts since his inauguration Tuesday — is seen as a victory for Brazil’s powerful rural lobby, which has long sought access to protected lands for logging, farming and other projects. It also signaled the apparent start of a new era of sweeping deregulation in Brazil, a country once lauded for its strides in environmental protection — including its stewardship of the world’s largest rain forest. Bolsonaro, a former army captain who was backed by the rural lobby, supports greater development of the Amazon, the assimilation of indigenous groups and reduction of environmental regulation”.

In Europe, some coverage focused on a continuing trend toward decarbonization and electric transportation. For example, media focused on Germany’s announced plans in January to phase out all of its coal-fired power plants over the next two decades. In addition to abundant media attention in the German press, journalist Erik Kirschbaum from the Los Angeles Times reported, “the announcement marked a significant shift for Europe’s largest country — a nation that had long been a leader on cutting CO2 emissions before turning into a laggard in recent years and badly missing its reduction targets. Coal plants account for 40% of Germany’s electricity, itself a reduction from recent years when coal dominated power production”. As another example, coverage noted record-setting electric vehicle sales in 2018. Journalists Camilla Knudson and Alister Doyle commented, “Almost a third of new cars sold in Norway last year were pure electric, a new world record as the country strives to end sales of fossil-fueled vehicles by 2025… The independent Norwegian Road Federation (NRF) said on Wednesday that electric cars rose to 31.2 percent of all sales last year, from 20.8 percent in 2017 and just 5.5 percent in 2013, while sales of petrol and diesel cars plunged”.

Meanwhile, the annual survey of global threats was released at the mid-January annual World Economic Forum. The survey showed climate change jump up the charts of concern, noting “of all risks, it’s in relation to the environment that the world is most clearly sleepwalking into catastrophe”. Journalist Joanna Sugdan from The Wall Street Journal reported, “The threat of a full-blown global trade war and rising political tensions between world powers are the dominant global risks, according to a report by the World Economic Forum ahead of its annual gathering in Davos, Switzerland, next week. Cyberattacks and climate change also feature high on the list of potential hazards drawn up from a survey of around 1,000 lawmakers, academics and business leaders for the group that organizes the Davos meeting”. Meanwhile, Guardian economics editor Larry Elliot wrote, “Growing tension between the world’s major powers is the most urgent global risk and makes it harder to mobilise collective action to tackle climate change, according to a report prepared for next week’s World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. The WEF’s annual global risks report found that a year of extreme weather-related events meant environmental issues topped the list of concerns in a survey of around 1,000 experts and decision-makers”. Read more …

Violent Crime Increases in Warm Weather

by Alison Gilchrist

Originally published on Science Buffs, A CU Boulder STEM Blog

I was 10 minutes into my interview with Ryan Harp before he showed me the most shocking piece of data I have ever had to emotionally process. For three years, Harp has been investigating the connection between climate and crime. At one point, Harp had to call the FBI– he was asking for some statistics about crime that the FBI collects from most police departments in the United States. Ten minutes into our chat, he was holding up a jewel case containing that data.

Hold up, I thought, and then vocalized. “Are you telling me that the FBI sent you three decades worth of detailed statistics about violent crime… on a CD?”

Did you know that the FBI employs over 35,000 people and has an annual budget of $8.7 billion? It has its headquarters in Washington, D.C. and has 56 field offices throughout the 50 states. Did you also know that the FBI still sends out 3GB of data on CDs?

Don’t worry, I stayed professional while processing this bombshell. Harp went on to explain why he needed that CD’s worth of data. Harp is a graduate student in the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), and the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences (ATOC) at CU Boulder. He’s currently working in the lab of Kristopher B. Karnauskas, studying the connection between local weather and crime. When he was sent this data, he was trying to correlate two very different datasets. The first dataset was from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and described the local weather all over the United States from 1979 to the present (sensibly delivered in a downloadable digital format). The second dataset described violent crime from the same time period (the CD).

Scientists have long known that crime rates increase during the summer and with warmer temperatures. There are two different theories about why this might be true. The first is that warm weather makes people more aggressive:

“When it’s really hot outside, your body gets physically agitated like you’re experiencing heat stress,” said Harp. “You’re just irritated and a little more likely to do something that you might not do. You’re cranky.”

The second theory, called the “routine activities” theory, is built around the idea that a crime needs three elements: a motivated offender (someone who wants to commit a crime), a target, and the lack of an obstacle to the crime, like a police officer.

“During pleasant weather, people are more likely to leave their house, go to restaurants or parks,” said Harp. “You’re just increasing the likelihood that those three things are going to come together.” This, in turn, makes crime more likely.

Harp was interested in two questions: first, which of these two hypotheses is correct, and can we prove it? And second: will a warming climate lead to more violent crime incidents?

This is where the two databases described above come in. Harp first split the United States into five different regions: the Northeast, Southeast, South Central, West, and Midwest. Next he categorized all the data points for climate and violent crime he had by region. He then compared temperature and crime to ask: if the temperature in a given month is higher than average, does violent crime also increase?

The answer is yes. In a publication for the journal GeoHealth, Harp showed that when the temperature is above average for any particular month, violent crime is also higher. This is true in all five regions, and the correlation is especially powerful in the winter months. This implies that it’s not just warm weather making people cranky—higher than usual temperatures in the winter are still not usually very high.

“This was our first piece of evidence that the second theory—the routine activities theory—was the stronger driver,” said Harp. “So when it’s warmer in the winter, people are out interacting more, and that leads to more crime.”

But Harp has even more evidence for the second hypothesis—that unusually warm weather brings perpetrator, target, and motive into closer proximity than usual. As well as looking at violent crime, he also looked at property crime. If the first hypothesis was true—that warm weather makes people cranky—then you wouldn’t expect property crime to increase with higher than average temperatures. When people get aggro in the heat, it’s usually because someone’s actions are more annoying than usual. But you wouldn’t expect a thief to be more likely to rob a house just because it’s hot… right?

But sure enough, property crime does increase with higher than average temperatures. This suggests that all crime increases when temperatures are higher than normal, not just a crime that revolves around people getting cranky. This lends more support to the second hypothesis: that warmer temperatures bring people who would commit crime out of their warm, cozy houses.

Harp’s conclusions are important for multiple reasons. This report accounts for seasonality—meaning Harp split up the results by month and showed that the correlation between warmer temperatures and a rise in crime is very high. Reports that don’t split up the data by month just show that crime and temperature are both seasonal, which is true but not a novel finding. Interestingly, there is still a seasonal trend—the correlation between an unusually high temperature and a rise in violent crime is stronger during winter months.

Harp also used relatively simple statistics, which he thinks speaks to the power of the trend that they’re finding.

“We created these regions, which allowed us to get past the random fluctuations from year to year and pull out the climate signal a lot more easily,” said Harp. “We were able to use really basic statistics and were able to detect the relationship without using a lot of complicated models.”

Harp, a climate scientist, thinks it’s important that this story is framed in the context of how climate could shape the health of future generations. Many people have researched how a warming climate could influence the spread of disease, but Harp thinks there could be health consequences to global warming we haven’t predicted. “When a violent crime occurs, the victim experiences physical and mental trauma, and their health is very negatively impacted,” said Harp. “We’re adding this in to the overall climate and health focus.”

Harp is interested in the next big question: will a warming climate lead to more violent crime incidents? This seems like an easy connection to make based on the results of this study, but it needs to be directly investigated before any conclusions are drawn.

A warming climate could have many impacts on human society and health. Questions about the future increasingly keep scientists, myself included, up at night. Will disease spread faster as disease vectors migrate into new regions of the world? Will rising oceans displace people from coastlines? Harp adds two more questions to my nightly worried thoughts: will violent crime increase as temperatures rise? And—most importantly—will the FBI ever learn about flash drives?