by Suzanne Tegen (CSTPR Visiting Scholar) and Alison Anson

Center for the New Energy Economy, Colorado State University

Photos above: A community once focused on coal is now a regional hub for recreational motorcycling. Credit: Back of the Dragon.

Coal plants are closing across the United States. The IEEFA expects 44 coal units will close in 2018, and 73 additional units are already scheduled to close by 2024. According to EIA reports, coal production peaked in 2008, and consumption in 2018 will drop below 1979’s record low and continue to decline. Electricity from coal now has a higher levelized cost of energy than natural gas combined cycle, wind, and utility-scale solar. Because of this, even with the EPA’s recent rollback of emissions regulations, utilities are unlikely to invest in new coal. Recent analyses[1],[2] reveal that continuing to operate some existing coal plants is now uneconomical, even without including social and environmental costs.

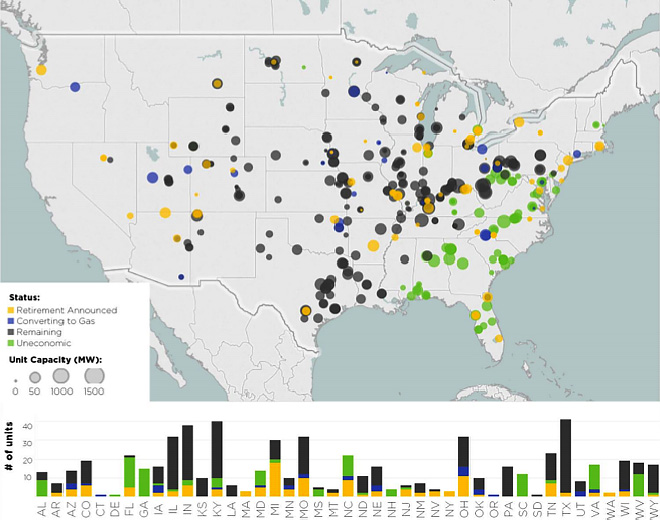

This map of the 2016 fleet of operating units is color coded to show announced retirements and conversions and units that are uneconomic compared to existing NGCC units. The bar graph show the total number of units by state. Credit: Union of Concerned Scientists 2017: A Dwindling Role for Coal.

Coal mining is an industry around which whole communities are built. As coal becomes increasingly uneconomical, and as coal mines and plants close down, miners, power plant employees, and their communities must find ways to transition.[3] The term “just transition” has been used to describe an equitable shift for coal workers and communities.[4],[5]

According to a study funded by the European Climate Foundation, “there is no recipe for implementing a just transition because mono-industrial regions are very different from each other and are defined by unique social, political, economic or cultural factors.”

According to a study funded by the European Climate Foundation, “there is no recipe for implementing a just transition because mono-industrial regions are very different from each other and are defined by unique social, political, economic or cultural factors.”

Policy solutions for coal transitions typically focus on workers or utilities’ return on investments. Coal communities can be mono-industrial, where industry is associated with identity and attachment to place. Providing alternative jobs and workforce development funding may not be sufficient to help the entire community deal with the shift away from a coal-based identity and livelihood.

Those responsible for successful transitions include policy-makers (including regulators), utilities (including plant owners), and community stakeholders (including workers). There are several current examples of successful coal community transitions. In Colstrip, Montana, policy-makers and others are providing new jobs in reclamation and clean-up. In Pueblo, Colorado, Xcel Energy will offer workers alternative jobs; and the community of Tazewell West Virginia has shifted focus from coal to tourism and natural resources.[6]

The solutions associated with transitioning coal communities should include a discussion of local justice and equity. Understanding and replicating successful transitions will require collaborative evaluation of the context-specific strategies developed by policy-makers, utilities, and communities. Socio-economic, cultural, and contextual perspectives will be integral to implementing these solutions.

[1] See RMI’s “Managing the Coal Capital Transition” for fiscal and capital impacts.

[2] The Carbon Tracker Initiative found that “42% of global coal capacity is already unprofitable.”

[3] Due to technological advances and automation, occupations such as farming and transportation may also require transitional solutions.

[4] Early use of the term “just transition” is attributed to Tony Mazzocchi around the late 1970s.

[5] Alexandru Mustata, 2017.

[6] See also www.justtransitionfund.org

Toward an Equitable Coal Transition

by Suzanne Tegen (CSTPR Visiting Scholar) and Alison Anson

Center for the New Energy Economy, Colorado State University

Photos above: A community once focused on coal is now a regional hub for recreational motorcycling. Credit: Back of the Dragon.

Coal plants are closing across the United States. The IEEFA expects 44 coal units will close in 2018, and 73 additional units are already scheduled to close by 2024. According to EIA reports, coal production peaked in 2008, and consumption in 2018 will drop below 1979’s record low and continue to decline. Electricity from coal now has a higher levelized cost of energy than natural gas combined cycle, wind, and utility-scale solar. Because of this, even with the EPA’s recent rollback of emissions regulations, utilities are unlikely to invest in new coal. Recent analyses[1],[2] reveal that continuing to operate some existing coal plants is now uneconomical, even without including social and environmental costs.

This map of the 2016 fleet of operating units is color coded to show announced retirements and conversions and units that are uneconomic compared to existing NGCC units. The bar graph show the total number of units by state. Credit: Union of Concerned Scientists 2017: A Dwindling Role for Coal.

Coal mining is an industry around which whole communities are built. As coal becomes increasingly uneconomical, and as coal mines and plants close down, miners, power plant employees, and their communities must find ways to transition.[3] The term “just transition” has been used to describe an equitable shift for coal workers and communities.[4],[5]

Policy solutions for coal transitions typically focus on workers or utilities’ return on investments. Coal communities can be mono-industrial, where industry is associated with identity and attachment to place. Providing alternative jobs and workforce development funding may not be sufficient to help the entire community deal with the shift away from a coal-based identity and livelihood.

Those responsible for successful transitions include policy-makers (including regulators), utilities (including plant owners), and community stakeholders (including workers). There are several current examples of successful coal community transitions. In Colstrip, Montana, policy-makers and others are providing new jobs in reclamation and clean-up. In Pueblo, Colorado, Xcel Energy will offer workers alternative jobs; and the community of Tazewell West Virginia has shifted focus from coal to tourism and natural resources.[6]

The solutions associated with transitioning coal communities should include a discussion of local justice and equity. Understanding and replicating successful transitions will require collaborative evaluation of the context-specific strategies developed by policy-makers, utilities, and communities. Socio-economic, cultural, and contextual perspectives will be integral to implementing these solutions.

[1] See RMI’s “Managing the Coal Capital Transition” for fiscal and capital impacts.

[2] The Carbon Tracker Initiative found that “42% of global coal capacity is already unprofitable.”

[3] Due to technological advances and automation, occupations such as farming and transportation may also require transitional solutions.

[4] Early use of the term “just transition” is attributed to Tony Mazzocchi around the late 1970s.

[5] Alexandru Mustata, 2017.

[6] See also www.justtransitionfund.org