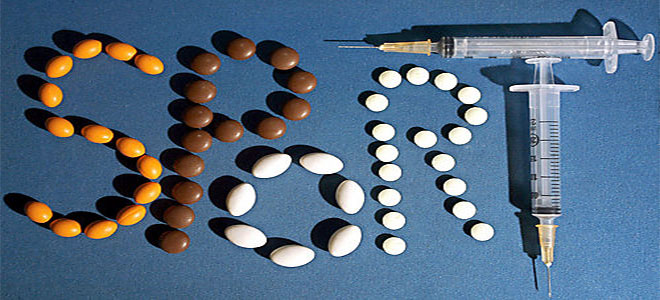

A Lack of Reliable Doping Data Puts the Spirit of Sport in Peril

Sporting Intelligence

September 30, 2014

by Roger Pielke, Jr.

Sport is in the news for a lot of the wrong reasons, from the scandal over the NFL’s response to cases of alleged domestic abuse to FIFA’s latest farce – the global football body ordering executives to return $27,000 watches given as gifts during this year’s World Cup by a grateful Brazilian FA in the same week FIFA sponsored a meeting on ethics.

One area where sport would seem to have its act together is in the area of anti-doping, or in clamping down on the use of prohibited performance-enhancing drugs. The biggest ‘catch’ in recent times could hardly have been more exemplary, in the shape of Lance Armstrong, who finally admitted to years of doping and was stripped of his seven Tour de France titles.

But all is not well with anti-doping efforts. Current policies are unaccountable, threaten athletes’ rights and risk the integrity of very sports that they are supposed to protect.

Anti-doping policies for the Olympic sports are implemented by the World Anti-Doping Agency, which oversees and coordinates the work of almost 200 national anti-doping organisations. WADA is overseen by governments, sports organisations and stakeholders under the provisions of a United Nations treaty. It is responsible for developing a list of prohibited substances and implementing a corresponding testing regime to identify and sanction those who break the rules.

I asked WADA some simple questions. How many athletes fall under testing regimes globally? How many athletes were tested in 2013? How many associated sanctions resulted?

The answers I received were shocking. WADA told me that they do not know the answers to these questions, explaining that the tests are administered by 655 different agencies which have signed on to the WADA Code and not all agencies share their results, even for elite athletes.

This means that important questions, at the core of any evidence-based anti-doping policy, cannot be answered. How many athletes dope? We don’t know. Is that number increasing or decreasing? We don’t know. How well does testing serve as a deterrent? We don’t know. And most importantly: Are anti-doping policies working?

Anti-doping officials tell me that the true purpose of testing is deterrence not detection. However, it is hard to know how well an emphasis on deterrence is actually performing without solid data.

The data that is available clearly suggests a problem. Current testing around the world detects evidence of doping in less than one per cent of samples, a number that hasn’t changed since 1985. Many – most? – of those are for recreational drugs, mainly marijuana, and approved medical usage.

By comparison, an anonymous survey of more than 2,000 elite track and field athletes conducted by WADA at the 2011 World Championships and Pan-Arab games found that 29 per cent and 45 per cent of respondents, respectively, admitted to the use of prohibited performance-enhancing drugs. Read more …