by Gayathri Vaidyanathan and Brittany Patterson, E&E reporters

ClimateWire

July 5, 2016

How small must a climate scientist’s carbon footprint be? How about a celebrity who calls for environmental protection? Or a politician?

Champions of the environment say they try to practice what they preach. But they also argue that demanding proof of eco-purity is a smokescreen used by climate skeptics and irrelevant to the larger issue of creating a systemic change in how people use energy.

“We will not solve the climate problem by telling people they can’t have toast,” said Ken Caldeira, an atmospheric scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science. “We will solve it by making sure that the wire from the toaster is connected to a wind turbine or a solar panel and not a coal plant.”

From former Vice President Al Gore to “hockey stick” climate curve scientist Michael Mann, those who put themselves in the climate change limelight feel the heat. “Leonardo DiCaprio Takes Private Jet to Accept Environmental Award,” blared Us Weekly magazine after the Academy Award-winning actor was honored by a clean water advocacy group in May. The New York Post similarly slammed President Obama for taking Air Force One to Paris last year to join “jet-setting representatives” from nearly 200 other countries to sign a climate change accord.

Conservative magazine National Review took aim at actor and anti-fracking activist Mark Ruffalo. Citing the fame he’s won for the role of Dr. Bruce Banner/The Hulk in “The Avengers” movie series, the piece opined that “Perhaps playing a character with two different personas has taught him how to lead the double-standard life of a typical Hollywood environmental hypocrite; one day, you’re flying to award ceremonies and making energy-guzzling action movies, the next day you’re raging against the very industries and technologies that make your comfortable lifestyle possible.”

Even the pope is not immune to attack. After Pope Francis released his environmental encyclical calling for climate action, a piece in the National Catholic Reporter noted the “darling of environmentalists” was poised to depart on a high-carbon Latin America tour. “The pope’s journey from Rome to Ecuador, Bolivia and Paraguay will inevitably involve a considerable amount of air travel, known to be a form of transportation that is incredibly damaging to the environment,” the piece said.

Increasingly, academics are entering the fray. A recent study published in the journal Climatic Change found people are more receptive to scientists they perceive as “green” (E&ENews PM, June 16).

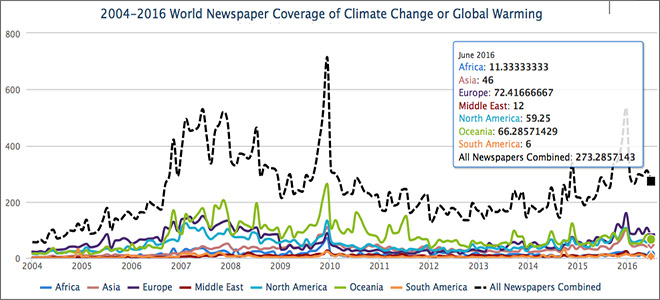

Meanwhile, a growing body of scientific literature is trying to tease out what impact celebrities can have on public engagement around climate change. The latest is an upcoming special issue of Environmental Communication devoted to the growing prominence of media and celebrity in environmental policies and how they are shaping the way we think about climate solutions.

Max Boykoff, an associate professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and a contributor to the upcoming special issue, said he has been intrigued by celebrities because of their power to inspire and to shape behavior change.

He said on the one hand, celebrities run the risk that their climate message is brushed off as a “fashion or fad” or that they are engaging in individual actions, which undermine larger societal momentum on climate change. But overall, he and others have concluded celebrities who take up the green megaphone create a net-positive by getting the public to think about climate change.

“U2 frontman Bono has commented, ‘Celebrity is a bit silly, but it is currency of a kind,'” Boykoff said. “This currency provides access to many people and places, from top leaders and everyday people to the podium at the U.N. and to people’s living room every evening.”

This power allows celebrities to reach an audience scientists may not. Media cover celebrities because people are curious and interested. It can also drive scrutiny when a celebrity preaches climate action but doesn’t follow through. Read more …

Notes from the Field: Community Action Plans – Learning the Art of Compromise in Serving Local Visions

Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Centre Internship Program

by Sierra Gladfelter – Zambia

July 2016

In Zambia, Sierra is supporting the monitoring and evaluation component of the ‘City Learning Lab processes’ Zambia Red Cross Society program. This includes supporting the facilitation and documentation of the First Lusaka Learning Lab for the Future Resilience for African Cities and Lands (FRACTAL) project, including contribution to the development of a learning framework and establishing a learning baseline, researching background materials and preparing reading materials in collaboration with the FRACTAL team and documenting learning during the Learning Lab interactions and compiling a learning report.

As we dodge potholes on the highway from Kazungula to Sesheke, the bush smolders on the shoulders of the road. Men pause in the heat of the day from clearing brush, squatting in small patches of shade on the side of the road. When I ask the Zambia Red Cross Society (ZRCS)’s Disaster Management Officer, Samuel Mutambo, seated beside me about the fires, his brow furrows. We are in the midst of a week monitoring activities associated with the Building Resilient African Communities (BRACES) program supported by the American Red Cross and are on our way to check on communities and deliver materials for the implementation of local action plans in Kazungula and Mwandi districts. Samuel, still troubled by the sight outside our window, launches into a thoughtful explanation. The forest burning is common here I come to learn, along with many other areas of Sub-Saharan Africa. According to Zambia’s Energy Regulation Board, approximately 75% of Zambians live off the grid without electricity (a rate that rises to 95% in rural areas), where firewood serves as one of their only forms of fuel, heat, and light.

“While rural Zambians often shoulder the blame for statistics on the growing rate of deforestation (according to the Times of Zambia, now approaching 300,000 hectares per year), the reality is not so simple.”

Even in Lusaka, Zambia’s rapidly developing capital, people who live with modern conveniences and access to more sustainable fuel alternatives often choose charcoal for cooking traditional dishes over their outdoor charcoal stoves. This urban consumption of forest resources has been exacerbated by the growing frequency of power cuts and load-shedding in urban areas which leaves vast swathes of Lusaka without power on a daily basis. Getting a meal on the table often means lighting up a bag of charcoal. Rural communities, like those along the road between Sesheke and Kazungula, serve as suppliers in a market currently estimated to be worth more than US $100 million (Ngosa, 2014).

The Zambia Red Cross Society (ZRCS)’s BRACES project seeks to combat such ‘destruction of the environment’ by empowering communities to manage local forest and land resources in ways that build rather than erode their resilience. While this aim is noble, its implementation is not always so straightforward on the ground, particularly when the approach depends on residents identifying their own needs through community action plans. This becomes evident during our first stop in a cluster of huts in the community of Sikaunzwe. We are delivering axes to the local head of the Satellite Disaster Management Committee (SDMC), so that remote communities gardening in the bush could clear a track to the main road to get their goods to market. Not having known exactly what we were delivering, I have to laugh at the profound irony as we, as part of a climate resilience intervention, stack hatchets in the shade of a hut that also has dozens of bags of charcoal waiting to be carried to the highway. I ask Samuel, trying to suppress the doubt in my voice, how we know that the axes will be used to clear the road and not in the production of local charcoal (certainly more profitable than selling tomatoes and okra!).

Samuel laughs. He knows where I am going. He assures me that the axes will be used for widening the road so that buyers may better access the vegetables grown through the BRACES program. Here, SDMCs carefully manage the tools they are provided and they cannot just be used for anything. Still, even Samuel admits that the possibility of the axes being used for other means remains. This, however, is the compromise he and others must be willing to make if they take seriously the self-proclaimed needs of communities. They have to learn to trust in order to build a reciprocal exchange with communities. The longer I have time to reflect on my own internal conflict over distributing axes, which could very well be used to exacerbate the forest’s felling, however, the less crazy it feels. Anything less than this commitment to local self-determination, I came to realize, would be paternal and colonial, another unidirectional intervention rooted in ‘education’ and coercion that so often occurs in the development industry and that the ZRCS works hard not to reproduce. When they give a community tools, they never have full control over how the community uses them. In the end, the lesson becomes about having a relationship that does not breed doubt but trust. Read more …