by Elizabeth Koebele

The Colorado River weaves through the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico, providing water for over 40 million people, 5.5 million acres of irrigated farmland, and countless environmental and recreational assets along the way (United States Bureau of Reclamation 2012). Images of the mighty Colorado rushing through steep desert canyons and filling massive storage reservoirs can make the river’s flow seem limitless.

In reality, however, the Colorado River is largely over-allocated, meaning that more water has been promised to users than typically flows down the river each year (Kenney 2009). Now, climate change and a rapidly growing human population are exacerbating water shortages in the region, making the development of effective strategies to manage the Colorado River one of today’s most pressing challenges.

Conversations about water management in the American West tend to start from the same premise: here, “whiskey is for drinking, and water is for fighting” (United States Bureau of Reclamation 2017). As there’s less of the Colorado River to go around for the diverse users that depend on it, greater conflict seems imminent. Threats of impending “water wars” over the Colorado have become so forged into the region’s collective mindset that they’ve started to show up as plotlines for popular dystopian fiction novels, like Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife.

Fortunately, a core group of public and private water professionals, academics, journalists, and river enthusiasts have started to push back against these narratives of insurmountable conflict. In an attempt to find a more sustainable answer to the region’s water woes, these folks are promoting management approaches that help stakeholders find common ground and incorporate the flexibility necessary to cope with greater water supply variability. Although their specifics vary, these approaches hold a core tenet in common: any good solution must incentivize people to share, collaborate, and negotiate creatively rather than divisively (Fleck 2016; Limerick, 2016).

Called collaborative governance processes by academics, such approaches typically convene diverse stakeholders to build trust, share knowledge, and develop consensus-oriented management actions (Ansell and Gash, 2008; Emerson et al., 2012; Gerlak et al., 2013). While these approaches may require more time and financial resources than traditional, top-down policymaking processes, scholars and practitioners alike claim that they can generate more legitimate management strategies that result in greater resource sustainability with widespread benefits.

Collaborative governance experiments have begun to crop up across the Colorado River Basin. For instance, the state of Colorado recently led a 10-year “Basin Roundtable” process in which diverse stakeholders collaboratively assessed their water needs and potential solutions, leading to the production of Colorado’s first statewide water plan. Across the Basin, four water providers and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation collaboratively developed and funded the Colorado River System Conservation Pilot Program, which financially incentivizes voluntary water conservation actions to raise water levels in the region’s major reservoirs. Collaboration has even caught-on internationally: in 2012, the U.S. and Mexico signed a landmark agreement that outlined pilot collaborative actions for better managing the transboundary river while also reviving the desiccated Colorado River Delta.

Determining the effects of these programs and policies will ultimately require a test of time. For now, however, they suggest that collaboration is a promising—and necessary—alternative to the “water is for fighting” mindset that has dominated Colorado River management for so long.

This post is based on research conducted by Dr. Elizabeth Koebele for her dissertation project “Collaborative Water Governance in the Colorado River Basin: Understanding Coalition Dynamics and Processes of Policy Change.” Please contact Elizabeth at elizabeth.koebele@colorado.edu for more information and related publications.

Photo caption: Lake Mead’s “bathtub ring” demonstrates the effects of long-term drought and increased demand on the Colorado River. Photo Credit: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

References

United States Bureau of Reclamation, 2012. “Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study: Executive Summary.”

Kenney, Douglas, 2009. “The Colorado River: What Prospect for “a River No More”?” In River Basin Trajectories: Societies, Environments, and Development, ed. F. Molle and P. Wester. Wallingford, U.K.: CAB International. 123-46.

United States Bureau of Reclamation, 2017. “Whiskey Is for Drinking, Water Is for Fighting!”, (January 23, 2017).

Fleck, John, 2016. Water Is for Fighting Over: And Other Myths About Water in the West. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Limerick, Patricia Nelson, 2016. Ditch in Time: The City, the West and Water. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Ansell, Chris, and Alison Gash, 2008. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4):543-71.

Emerson, Kirk, Tina Nabatchi, and Stephen Balogh, 2012. “An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22 (1):1-29.

Gerlak, Andrea K., Tanya Heikkila, and Mark Lubell, 2013. “The Promise and Performance of Collaborative Governance.” In Oxford Handbook of U.S. Environmental Policy, ed. S. Kamieniecki and M. E. Kraft. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 413-34.

New Data for Old Problems

by Justin Farrell, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Yale University

What should social scientific research look like in this so-called age of “big” data, where everything is connected, and seemingly everything is digitized? Here I want to briefly reflect on some of the promises of new data and research methods, and consider the ways that we might integrate these computational approaches with traditional qualitative fieldwork. My main claim is that while the Internet has certainly transformed the world, our methods for understanding and explaining social life have not kept pace.

We live our life in a huge connected network. We check emails, make cell phone calls, text our friends, swipe our credit cards, communicate on social media, post videos, send money, or purchase our goods. Almost every transaction is recorded digitally, as doctors create digital records of our health, stores log our buying patterns, and so on, and so forth. Until recently, these behaviors—such as a simple phone call or simple store purchase—were not easily traceable. These digital “breadcrumbs” were not gathered. There were no digital timestamps or digital text duplicates of a handwritten note, or a cash exchange. Of course, this raises ethical concerns about privacy, of which certainly need to be front and center as scholars working outside of the private sector figure out how to incorporate this data into research for the public good.

In addition to the things we use everyday, such as cell phones, tablets, and computers, there is also a burgeoning “Internet of Things” that provides opportunities for data collection to inform social scientific study. Examples might include environmental monitoring commonly used in other fields, such as sensors for water quality, atmospheric and soil conditions, movements of wildlife, earthquake and tsunami sensors, gas and wind turbine sensors measuring efficiency and cleanliness of energy. All of these (can and should) be of use for social research. Or consider human health, such as heart monitors or movement monitors, all of which provide real-time streams of data and can be monitored and collected remotely. All of these types of data are much more accurate than conducting a survey to ask for self-reports.

On top of all of this new data that is created and recorded every day is the digitization of old information, such as books, newspapers, photographs, speeches, television programs, websites, and any other written or spoken word. For example, Google is currently archiving all books ever written. They write, “Our ultimate goal is to work with publishers and libraries to create a comprehensive, searchable, virtual card catalog of all books in all languages that helps users discover new books and publishers discover new readers.” Google has now scanned more than 25 million books, available to read, search, and analyze.

Or consider the Internet Archive, where you can search this history of more than 286 billion historical web pages (!!!), 3.3 million movies, or 200 terabytes of government material. Still more, consider the HathiTrust, a large-scale collaboration between dozens of universities and libraries, who has archived tens of millions of books and articles that are all full-text searchable.

This flood of new data is exciting, and must be taken advantage of by folks in academia. Our methods training must adapt—especially to include text analysis and network analysis—not because of an obsession with the shiny new objects, or because it is trendy, but because it is our responsibility as researchers to use the best data available in service of our research questions, theories, and applied solutions.

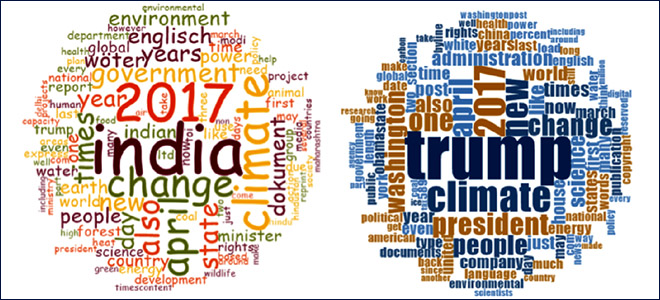

To conclude, I want to provide a few concrete examples. The first is a study I conducted to map out in great detail, and at full-scale, the climate change counter-movement. Drawing on some of the sources described above, I collected every text ever written from every climate contrarian organization (more than 39 million words), as well as mapping out the entire social network of organization and individuals with ties to the movement. You can read these papers here:

Farrell, Justin. 2016. “Network Structure and Influence of the Climate Change Counter Movement”, Nature Climate Change 6(4), 370-374.

Farrell, Justin. 2016. “Corporate Funding and Ideological Polarization about Climate Change”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(1), 92-97.

The second is from my recent book on environmental conflict, where I paired the data and methods described above with in-depth qualitative fieldwork. My goal was to discover something new about the nature of conflict over environmental science, as well as to show how traditional ethnographic fieldwork can provide ground truth, working in tandem with computational methods.

Farrell, Justin. 2015. The Battle for Yellowstone: Morality and the Sacred Roots of Environmental Conflict. Princeton University Press.

In the end, we must use all the tools at our disposal in order to continue to move forward to creatively address the problems at the intersection of society, politics, and environmental science.