A team of CSTPR researchers is on the story

University of Colorado Arts & Sciences Magazine

April 30, 2015

By Meagan M. Taylor

It’s not an overstatement to say that Boulder is an international hub for environmental devotees: atmospheric research experts and polar-bear habitat activists alike.

But Max Boykoff, associate professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, has a unique vantage point on the subject of climate change. Instead of measuring icecap melt, he measures social reactions to such events, on a global scale.

You might say he analyzes the analysts.

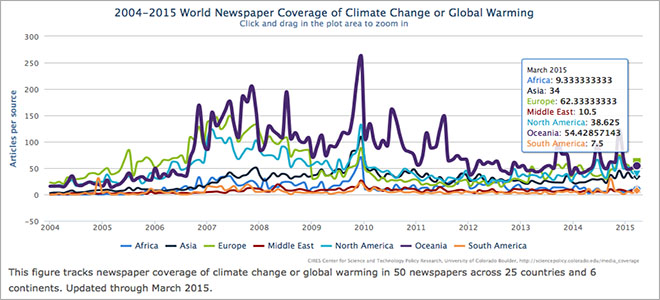

Boykoff’s Media and Climate Change Observatory (MeCCO) project examines global mass media coverage of climate change topics, to gauge the scope and level of public dialogue on the wellbeing of spaceship earth.

“We developed ways to look at where and when the conversation is happening,” he says of the research methodology. “We can tell what events indicate ebbs and flows in coverage, and what kinds of things facilitate the conversation or impede it.”

His idea to create MeCCO stemmed from a conversation with a colleague at Oxford University, where Boykoff is a senior visiting research associate in the university’s Environmental Change Institute.

“We were interested in climate coverage between the UK and U.S. media, but a lot of the conversation was speculative” he says. “We said we should have some kind of monitoring system for media coverage.”

The idea led him to found a graduate project for the CU-Boulder’s Center for Science and Technology Policy Research (CSTPR), housed within the Cooperative Institute for Research and Environmental Sciences (CIRES).

The MeCCO team is composed of Boykoff, five graduate students, and post-doctoral researcher and visiting fellow Gesa Luedecke.

Each month, the team extracts publications containing the terms “climate change” or “global warming” from 50 sources in 25 countries, accessed through record databases Lexis Nexis, Proquest and Factiva. Boykoff also has counterparts at climate research institutes in Spain and Japan who compile articles from their national databases.

“I think this project is a really valuable resource,” Luedecke says. “It’s objective, and it reflects what is important to our society.”

Objective, because the researchers cull data based on a consistent set of criteria. They target publications with a large and diverse geographical range, broad circulation, and reliable access to archives over time.

Access to archives is particularly important because not all media warehouse their data, Boykoff explains. Television media archives, for instance, may store content for only a few days, and outside of the U.S., saved content is virtually nonexistent.

While TV news and Twitter seem to be the most ubiquitous messengers of death-by-carbon-emissions, MeCCO uses only newspaper sources, for their consistency and predominance.

“Newspapers are influencers,” Boykoff says. “Print media is able to dig in substantively into issues.”

But sorting through the deluge of information published on climate change is much more complex than just counting newspaper clippings.

The team has indexed four factors that determine the quantity and range of coverage: political events, scientific findings, meteorological events and social inputs.

Political events and publication of new scientific research may be the most obvious factors that cause a ruckus in the press.

The November 2014 joint announcement by the United States and China to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions in the next 10 to 15 years preceded a spike in coverage that month. Read more …