JSTOR Daily

August 2, 2016

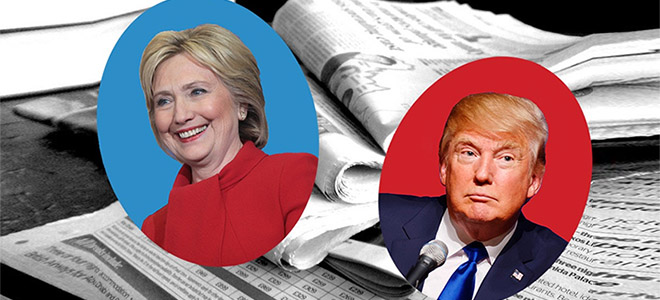

The Washington Post editorial board recently released a scathing op-ed calling Republican nominee Donald J. Trump a national problem. Citing his Republican National Convention speech and messaging, the board notes that despite the board’s desire to remain neutral in its coverage of both candidates and conventions (AKA journalistic integrity), it cannot condone Trump’s lack of qualifications, hateful campaigning, misdiagnosis of American politics, politics of division, and contempt for “constitutional norms.” The board makes its case clearly and concisely, making clear it belief that Trump is dangerous to American democracy.

Democratic nominee Hillary Rodham Clinton has also come under attack for issues of ethics and integrity, with the ongoing debates surrounding “her handling of classified information on a private email domain as secretary of state” and the recent Democratic National Committee email WikiLeaks.

So how does one report the news in a fair and unbiased format when there might be moral issues standing in the way?

In 2011, Trevor Jackson asked just this, although in reference to something much more scientifically rather than politically-oriented. Jackson’s article “When Balance is Bias: Sometimes the science is strong enough for the media to come down on one side of a debate,” can also apply to how, when, and under what circumstances journalists should weigh in and pick sides.

Jackson begins by telling the tale of Emeritus Professor Steve Jones who was hired to examine the “impartiality and accuracy of BBC’s coverage of science.” In his findings, Jones reported concern about the BBC’s “due impartiality” guidelines and the effect they might be having on readers. He found that “in their quest for objectivity and impartiality—entirely understandable aims in coverage of politics and arts—[the BBC] risked giving the impression in their science reporting that there were two equal sides to a story when clearly there were not.”

In his own words, Jones noted, “[t]here is widespread concern that [the BBC’s] reporting of science sometimes gives an unbalanced view of particular issues because of its insistence on bringing in dissident voices into what are in effect settled debates.” He cites multiple examples such as media coverage of the MMR vaccine and climate change, both cases where Jackson notes that journalists “made people think that scientists themselves were divided…when they were not,” thus creating a “false balance.”

It is precisely this “false balance” and resulting forced neutrality that Jackson continues to explore in his case studies. He cites investigative journalist Nick Davies who “says that the insistence on balance is one of the factors that stops journalists getting at the truth.” He also cites Maxwell Boykoff whose book Who Speaks for the Climate? suggests that “the journalistic norm of balance in news reporting” has in turn impacted both climate policy and related decisions by “amplify[ing] outlier views.” Read more …