Flight director: Keeping the G-IV and its crew safe during research flightsFebruary 4, 2016by Lisa Darby (NOAA)

Flight director: Keeping the G-IV and its crew safe during research flights

February 4, 2016by Lisa Darby (NOAA)

HONOLULU, Hawaii—The observations and weather forecasts have been carefully analyzed and discussed. The final flight plan has been tweaked for maximum success and filed with the FAA. The plane has taken off and begun launching dropsondes. But what happens when the G-IV is mid-flight, and the weather along the planned flight track is not safe enough to proceed to take data as planned? This is a time when the flight director goes into action, acting as the interface between the pilots, the research scientists, and air traffic control.

The NOAA Aviation Operations Center employs flight directors as part of the NOAA research aircraft crews. Flight directors are trained meteorologists who are experts at aviation safety. While the research meteorologists are focused on capturing data to better understand and forecast particular meteorological phenomena, the flight director has a different meteorological focus – keeping the research plane safe, along with ensuring we get the best scientific measurements given the flight conditions. Will there be turbulence? A threat of icing? Volcanic ash? In the case of the El Niño Rapid Response G-IV flight on February 2, convection was rapidly developing along the flight path, contrary to previous flights when the convection decayed during the flight.

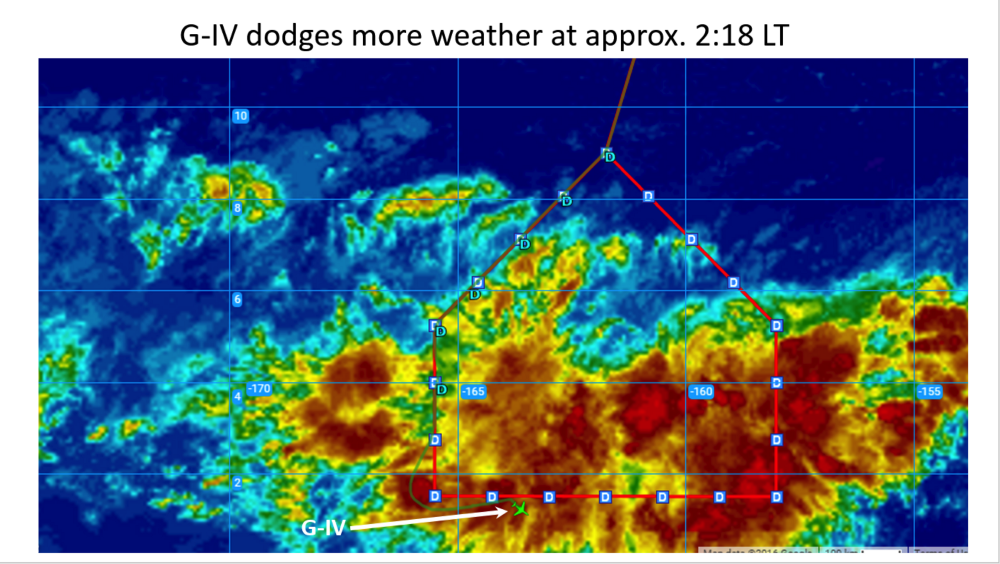

Screen shot of the G-IV flight track superimposed on an IR satellite image of the convection the G-IV was surveying (courtesy of Allen White). The green plane icon indicates the position of the G-IV, the ‘D’ symbols indicate the dropsonde launch positions.

Screen shot of the G-IV flight track superimposed on an IR satellite image of the convection the G-IV was surveying (courtesy of Allen White). The green plane icon indicates the position of the G-IV, the ‘D’ symbols indicate the dropsonde launch positions.

As we approached the southwest corner of the house-shaped flight track, about 1000 miles into the flight, the G-IV had to divert away from the planned flight track, heading west and then south of the track in order to avoid the convection. What is not shown in this figure is that we continued flying south, almost to the equator (as far south as 0.1° N!). During this time, the pilot, LT Ron Moyers, and the flight director, Mike Holmes,

The pilot, Ron Moyers (left) and flight director, Mike Holmes (right) looking at satellite data while discussing options on how to proceed with the flight (photo: Lisa Darby).

The pilot, Ron Moyers (left) and flight director, Mike Holmes (right) looking at satellite data while discussing options on how to proceed with the flight (photo: Lisa Darby).

consulted with the team on the ground in Honolulu, who had access to more real-time weather data than what is available on the G-IV, and the onboard scientists. Options included attempting to continue along the planned flight track back to Honolulu, land on Kiritimati Island, or do a U-turn and fly back to Honolulu along the west side of the house. The convection on the east side of the house was changing too quickly to plot a safe route through it, and there wasn’t enough fuel for additional diversions if needed. Kiritimati was under the convection we were surveying, so we were not able count on being able to land there. Moyers and Holmes made the decision to do a U-turn and head back to Honolulu. Ultimately the pilot is responsible for the aircraft’s safety, and has the final word on how to proceed. Once back at the airport, LT Moyers told us this was the first time he had to turn a flight around.

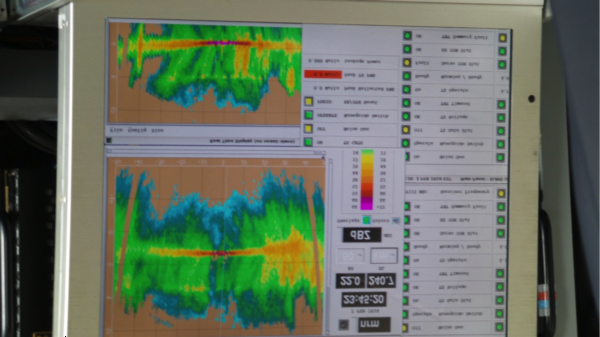

Screen shot of the Tail Doppler Radar display (photo: Lisa Darby)

Screen shot of the Tail Doppler Radar display (photo: Lisa Darby)

All-in-all, we got great data, we just weren’t able to survey the convective outflow around the whole system. Thirteen dropsondes were launched, and a wealth of Tail Doppler Radar data were collected.

NOAA’s Kelly Mahoney (left) and Lisa Darby (right).

NOAA’s Kelly Mahoney (left) and Lisa Darby (right).

By CIRES on February 5, 2016.

Exported from Medium on January 12, 2017.