The Life of a Buoy “Hopper”March 10, 2016by Dan Wolfe (CIRES) and Matt Winterkorn (NVision Solutions & NOAA NDBC)

Buoy deployment on fantail. Extra buoys, frames, and spools of cable spread around the deck making for challenging working conditions.

Buoy deployment on fantail. Extra buoys, frames, and spools of cable spread around the deck making for challenging working conditions.

The Life of a Buoy “Hopper”

March 10, 2016by Dan Wolfe (CIRES) and Matt Winterkorn (NVision Solutions & NOAA NDBC)

PACIFIC OCEAN — Buoy operations are the heart of the NOAA Research Ship Ronald H. Brown and the primary focus of this cruise. With her large “A” frame and heavy lifting cranes on the fantail (back of the boat) she can easily handle the TAO (Tropical Atmosphere Ocean array) buoys. A reminder: the TAO array is an international effort started in 1985 after the 1982–1983 El Niño (one of the strongest ever), designed primarily to study climate variations related to El Niño and the Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in the Pacific Ocean from year to year.

Art work added to buoy before deployment by Bosun Bruce. Fabi is one of the hard-working deck crew.

Art work added to buoy before deployment by Bosun Bruce. Fabi is one of the hard-working deck crew.

The ship can’t handle this task alone, though — it takes a well-seasoned crew to do the job efficiently and safely. From the Captain down to the able-bodied seamen (and women) they spend countless hours in all sorts of conditions (Tropical weather included on a normal TAO Cruise like this one). The deck crew is headed by someone I’m told is one of the best, Bosun Bruce Cowens, and it shows with his leadership where it matters most: during buoy recovery and deployments.

As Balloonatics, we know almost nothing about what goes on in the life of a “Buoy Hopper.” This old nickname was given to National Data Buoy Center (NDBC) technicians who would fearlessly hop onto a buoy in the water to replace sensors — something I can only imagine as a dangerous and unique experience — rather than bringing it onboard (as is done on this cruise).

Matt Winterkorn, one of our balloon crew, does work on the data quality control side of the TAO program at NDBC. On this cruise, Matt is getting his first look at TAO buoy Operations up-close and personal, including how the data are collected in the field.

Barnacles that have accumulated underneath the buoy. Each buoy gets stripped of the barnacles, power washed and repainted if needed, so it’s ready for the next deployment.

Barnacles that have accumulated underneath the buoy. Each buoy gets stripped of the barnacles, power washed and repainted if needed, so it’s ready for the next deployment.

Besides launching balloons, Matt pitches in to help his colleagues on deck record information about the instruments being deployed, help with heavy lifting, and even clean off the barnacles and fishing line that can accumulate after sometimes more than a year in the field. That’s all for my take on buoy operations — now let me turn it over to Matt.

Buoy operations on board the Ron Brown is hard work. Teamwork and communication are essential and for the NDBC team, the Buoy Hoppers, that starts with their fearless leader, Will Thompson. Will has many years of experience at sea working with mostly TAO buoys, but also Weather and Tsunami or DART (NDBC Tsunami buoy network) buoys, and his presence on a TAO Cruise is priceless. As the lead for buoy operations, Will must not only possess knowledge and experience but also patience in an often demanding Tropical environment.

Stefan caught this tuna which became dinner the next night.

Stefan caught this tuna which became dinner the next night.

Then we have electrical technician Stefan Becerra on his fourth TAO cruise. Stefan has taken on more responsibility under Will, including the general assembly of buoy components, data quality control, metadata management, and sending log files back to NDBC’s Mission Control Center (MCC) at Stennis Space Center, MS, where I work. (Stefan also caught a good size tuna the other day!) These log files contain sensor property numbers and deployment and recovery times that are vital for sensor tracking and ultimately the release of TAO data to the Global Telecommunications System (GTS).

Other new additions to this TAO Cruise (besides me) are mechanical technicians Jim Turner and Robert Taylor (not James Taylor as initially written on their stateroom door!). Jim and Robert have taken on many new tasks and handled them well, despite not feeling the greatest as we encountered gale force winds and high seas right out of Honolulu.

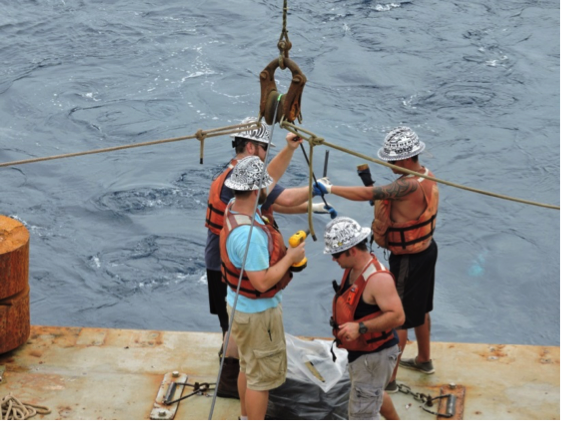

The Buoy Hoppers working as a team installing instruments before reeling out on the nilspin: Will (blue shirt), Robert (directly behind Will), Jim (right front), and Stefan (right back).

The Buoy Hoppers working as a team installing instruments before reeling out on the nilspin: Will (blue shirt), Robert (directly behind Will), Jim (right front), and Stefan (right back).

They install the heavy chains that will secure the buoys once deployed, set up each system with sensors, check, initial reporting, and install (and remove on the recoveries) countless sensors from the nilspin (a mooring cable that is extremely durable). Just for reference, a typical buoy configuration is 10 subsurface ocean sensors down to 500 meters depth.

Before the cruise is over, the Buoy Hoppers will work 13 buoy sites, out of 55 total in the TAO array. At each site, the first thing they do is recover the old buoy and then deploy the newly configured and assembled buoy. This can take an entire day, but this maintenance is critical to the health and longevity of the TAO buoy array.

Deployment of sensors on the nilspin line going into water. The left sensor is a Chipod piggy-backing from Oregon State that measures mooring microclimate, and the right sensor is a Sontek sensor measuring ocean current.

Deployment of sensors on the nilspin line going into water. The left sensor is a Chipod piggy-backing from Oregon State that measures mooring microclimate, and the right sensor is a Sontek sensor measuring ocean current.

The data collected are useful for short-term forecasting as well as adding to the climate record. Besides the near real-time data collected by the array, there is also “delayed mode” data that is retrieved from the subsurface sensors below the buoy after their recovery. These data actually account for, on average, an additional 15 percent more data than is captured in near real-time. This TAO data would not be possible without the efforts of the Buoy Hoppers!