Dear Friends and Colleagues,

The 4th week (December 4-16th, 2010) was long and dramatic for the A-130 lidar team because we went through hell to reach the heavens!!!

First, what happened in the heavens?

I am very happy to announce that we obtained the first Fe signals (372 nm) from Arrival Heights on December 16, 2010. It was at 1:50am UT, and the layer’s peak was at 96 km – quite high, indicating PMC heterogeneous removal effect! Although there is still a long way to go, the first light is a milestone for the lidar project!

The significant milestones:

December 9th, 2010 – My PhD student Zhibin Yu arrived in McMurdo, he is our winter-over scientist and will operate the lidar through the winter.

December 13, 2010 – First time to shoot the lidar beam to the sky, and we obtained the weak Rayleigh signals through clouds and huge cloud signals

December 14, 2010 – First time to get good Rayleigh signals by 372nm lidar channel, but trouble with the seed laser prevented us from getting Fe signals

December 16, 2010 – First time to get 372nm Fe signals at 1:50am UT

Second, how did we reach the heaven?

There weren’t any other ways except through hard and creative work of all team members under the extreme conditions. Shipping damage has been an on-going problem with this lidar project. Besides the issues I mentioned before with a power console, two laser heads, and mounting frames, another odd thing happened on December 9th — we found seawater in the 374nm optical telescope! We just couldn’t believe our eyes after the telescope was tilted to horizontal direction and at least a cup rusty red water came out of the bottom of the telescope. How did it get there? We asked the cargo expert Michael Davis to inspect it at Arrival Heights, but no one could provide a reasonable answer, especially considering the telescope was well sealed. Condensation? It would be too much condensation!

Actually, even before we found the seawater inside the 374nm telescope, we had already found a strange phenomenon on the 372nm telescope the previous day (but fortunately, this telescope was at least dry!). The Schmidt plate was very dirty but we couldn’t clean the dirt off the plate with methanol (a standard optics cleaning solvent)! After a few tries without success, I concluded that these marks must have been from seawater or seawater vapor. Water marks have to be cleaned with water, and then methanol helps to remove the residue after water dissolves the water marks. This was an experience I gained when working with Dr. John Walling in December 2009 at Light Age, Inc. So we tried to use deionized water first, and then methanol – the approach worked very well.

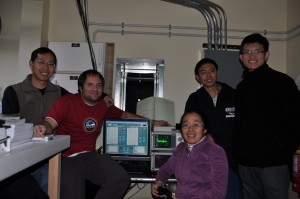

A happy group photo of all five lidar team members at McMurdo, Antarctica. From the left are Zhibin Yu, Wentao Huang, Xinzhao, John Smith, and Weichun Fong. Wentao is a CIRES research scientist in my group, while Zhibin, John, and Weichun are three of my PhD students. Mr. Zhibin Yu, a second year PhD student in the University of Colorado at Boulder, joined us in McMurdo on December 9th, 2010. He took the winter-over scientist position for the lidar project. After the original candidate failed physical qualification (PQ), he was very brave to take on this position and dared to face both the lidar technical challenges and the physical and psychological challenges for working in Antarctica. All members have worked extremely hard from Boulder to McMurdo for the success of this project, but we are very happy after we got the first lidar signals.

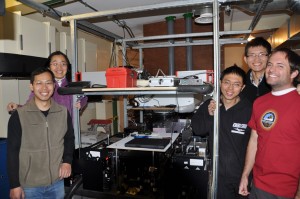

The lidar team with the lidar transmitter – we were so happy. We were shouting “Fe signals” when the camera shutter was triggered by a remote control.

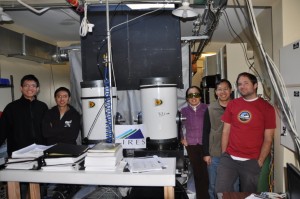

The lidar team with the lidar receiver – we were quite relaxed after the first Fe signals were obtained. Both CIRES (Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences) and ASE (Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences) signs were shown as we belong to these two institutions and have received great support from both of them! The eye wear on me was the laser goggles for Alexandrite lasers.

Our research scientist, Dr. Wentao Huang, took on this challenging task to handle the over 40-cm optics, and did an excellent job to restore the optical performance of the Schmidt plates.

John Smith was cleaning the primary mirror of the telescope. We had to do it after the shipment by boat, but it’s risky to do so. A drop of a flash light (for illuminating the mirror in the cleaning work) could break the over 40-cm optic and it is impossible to find replacement within a short period. I warned the team “I would rather have dirty optics than broken optics”. John came up with a brilliant idea as shown in the photo – he secured the flash light on his neck!

Two over-worked and over-stressed team members, Weichun and Wentao. But their spirits are still up, and they keep going forward!

Final remarks – a lesson learned and my birthday in Antarctica

To be honest, the first Fe signals should have come on December 14, 2010 when we got the first good Rayleigh signals. As I quoted above, we ran into seed laser troubles. But this wasn’t a real problem of the laser, but a wrong connection of a cable. How did it happen? One of our team members wanted to re-route a cable for the seed laser. In doing so in a hurry, the cable was wrongly connected to a BNC connector. But since I made the original connection and the seed laser worked well the days before, I didn’t suspect the cable connection could be wrong. This wrong connection disabled the PzT tuning, so the seed laser couldn’t be tuned to the desired wavelength in single mode. I tried all my approaches, which all worked before, to tune the laser but just wasn’t successful. For a moment, I was thinking about why Rudolf and Mark of Toptica even sold this damn DL-100 ECDL laser to me. Their DL-pro ECDL is so much better! By 3am in the morning, I stared at the front panel of the laser control unit and suddenly realized what went wrong. Once the cable connection was corrected, we tuned the seed laser to the desired wavelength within 10 minutes. Unfortunately, the sky had become totally cloudy, so no chance to get signals. Oh, well, a lesson learned — we will check cable connections first in the next time!

A shining point on my birthday was the arrival of Zhibin Yu – our winter-over student. I went to Chalet to greet him when he got off the shuttle. With lots of worries of instruments and frustrations of bureaucracy in mind, that was the best smile I could put on that day.

December 9th is my birthday, and I had celebrated on the ice before — at the South Pole in 1999 and 2000, and at Rothera in 2002 — all were very pleasant and memorable. Originally I planned to get the first Fe signals on December 9th, and then celebrate both my birthday and the first lidar signals on the same day. Unfortunately, the beam propagation approval didn’t come through so no signals at that time. So I held off the celebration, and I tried to handle the “crisis” on my birthday — the seawater inside our 374nm optical telescope, and a potential problem with the Bristol wavelength meter (WLM). A good thing was that both problems were resolved quickly, and we remembered the good advice from John Theodorsen of Bristol on the WLM. John and his colleagues had given us very good technical support 11 years ago when we did the campaign in the airplane to the North Pole and then at the South Pole. It is great to learn that the Bristol WLM can stand for drop tests, and it continues working well for us in the lidar campaigns.

Patience, persistence, and our hard and creative work will finally pay off! Many thanks to our brilliant research scientist and PhD students!!!

Sincerely,

Xinzhao