What does field research look like? It’s not always glamorous, despite the beautiful icescapes and rugged living conditions. As a grad student whose research up until a few months ago mostly involved creating numerical models to solve nonlinear partial differential equations, the prospect of designing and building a field setup to measure permeability on the ice sheet was wildly exciting, and also somewhat daunting. But with the little grants and awards I managed to acquire, I started piecing it together as a side project in collaboration with the FirnCover team. I also want to acknowledge the pro bono consulting services of Eli Weber, a mechanical engineer at Apex Companies, whose experience and advice have been enormously helpful in designing these permeability tests.

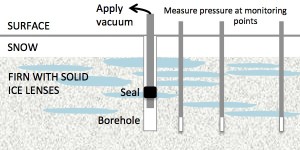

To get a better idea of how much water could infiltrate and refreeze in the firn, we’re borrowing a technique that is used in groundwater remediation to determine properties of the soil, particularly how well the pore space is connected – and how freely air (or water) can flow through it. In soil, you apply a vacuum in one well and monitor the pressure response in another well. We can do the same thing in firn and ice, except that our wells are called boreholes!

So yes, if it sounds like we’re going to attach a shopvac to a pipe going down into the ice sheet – that’s it exactly. This is basically what the setup looks like, on a ‘bluebird’ testing day up on Berthoud Pass back in February (11,000 ft elevation, about an hour drive into the mountains from Boulder, Colorado):

And here are the sensors we’ll use to monitor the vacuum and the pressure response (some analog gauges and an electronic pressure transducer connected to a datalogger):

Of course, conditions in Greenland will be different, but testing the system in Colorado gives us a feel of how well the system will work, and helps us to anticipate problems we might encounter on the ice sheet. Up on Berthoud Pass, we were only drilling into about 1 m of wind-packed snow (and ‘drilling’ here consisted of pounding a PVC pipe into the snowpack and vacuuming out the core). In Greenland, we will be drilling down as deep as 16 m (about 53 ft) into the firn, through solid refrozen ice layers in some sites.

You might be thinking that the setup looks, well, kind of janky. You’re right, it does – but it works. And the more I talk to other, more experienced field researchers, the more I realize that that is really the nature of research, and of building a prototype system (especially on a low budget and short time scale!). You spend time wandering around the local hardware store, you borrow tools from people you know with ‘real jobs,’ and you get creative. It might not be a beautiful, sleek, shiny setup – but if you can do good science with it, that’s what matters.

So let’s take a shopvac up to Greenland next week!

Thanks for such a clear explanation. Wishing you safe travels and successful work on the ice.