A week from today, our FirnCover team assembles in Kangerlussuaq for a month-long traverse across Greenland’s vast interior ice sheet. The majority of prep-work, cargo shipments and customs hassles are done. A page-long “ToDo” list remains on my desk, the odds and ends of prepping science and tidying affairs before 5-6 weeks abroad. But sometimes in the din of preparations, a moment forces me to take pause.

Yesterday, April 11th, a high-temperature pressure ridge settled over Greenland and began thawing in earnest, with 12% of the ice sheet experiencing melt. It set records, breaking the previous record (the earliest day with ≥10% of the ice sheet melting) by more than three weeks. Small headlines have already started popping up:

Greenland sees record-smashing early ice sheet melt

Ever since the record 2012 melt completely shattered observational records for Greenland (breaking the previous 2010 record melt year, after the 2007 record before that, and did I also mention 2005, and 2002?), scientists have patiently taken measurements and waited for the next “big one” to hit. No one can predict the short-term weather with certainty, and it *could* happen that 2016 cools back down and reaches only modest melt levels through the rest of Spring and Summer. But melt in Greenland, over this wide an area, this early in the season, is not supposed to happen.

We plan our work for late April or early May, usually in the “winter maximum” window. Typically, we dodge the onset of Greenland’s high-elevation melt by at least several weeks. Our drilling requires this. Putting a warm, wet drill down a cold borehole (still -20°C from the previous winter’s cold) is a recipe for getting a $10,000 ice drill irrevocably stuck, far deeper than we could hope to dig and retrieve it. We don’t like to lose $10K drills more than we need, so we avoid the melt season at all costs, even if it means arriving and working in -40° temperatures.

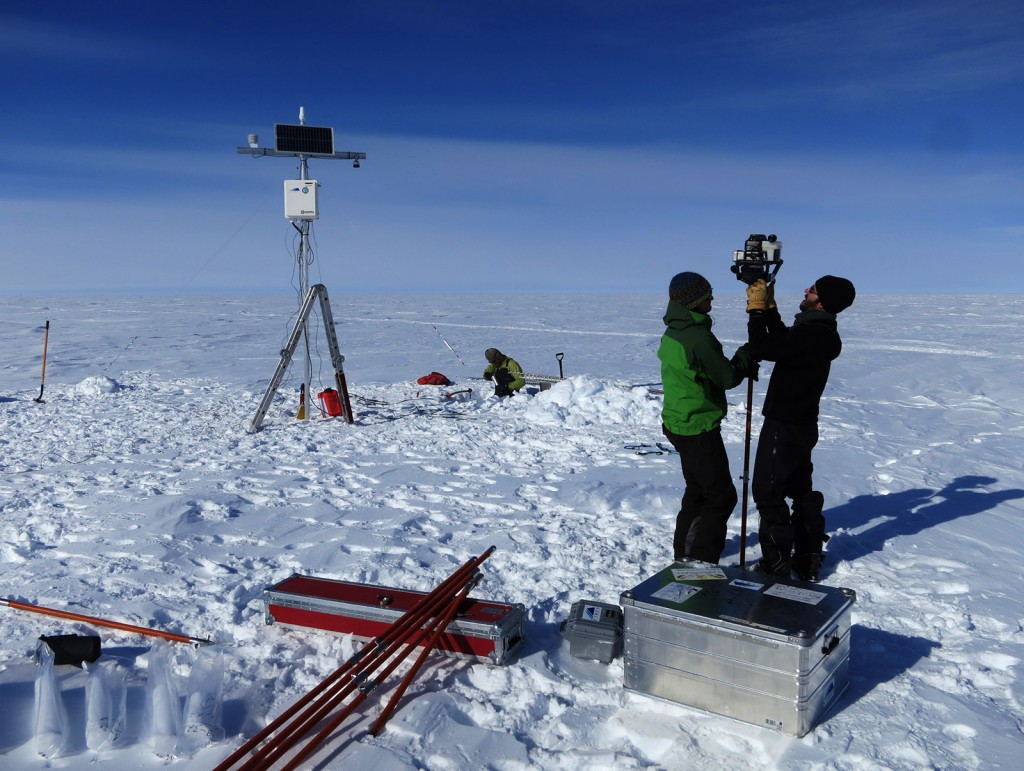

Drilling and logging, with a new partially-assembled FirnCover tower at Summit camp. Photo taken by Mike MacFerrin, 2015.

But sometimes nature has other plans. The 2016 melt has beat us by 2 weeks, with temps already above freezing at two of our lowest stations (1840 and 2100 meters above sea level). Weather should cool down again and freeze back up, and we’re hoping to encounter a cold, stable snowpack when we arrive. But melt has started, and this worries us.

This feels eerily similar to our 2012 season, when low Arctic sea ice levels, warm Spring temperatures and low accumulation rates were precursors to a record-setting melt summer. Those preliminary dominoes are all set again, right now. I remember our Twin Otter plane requiring 13 attempts to lift our team off the ice as daytime temperatures slowly turned the snow into a soft slush field, on the 5th of May 2012 at KAN-U. It’s now the 12th of April 2016, and KAN-U started melting yesterday.

We plan to install some of the most comprehensive measurements of Greenland’s surface mass balance (and its response to summer melt) currently seen anywhere on the interior ice. If successful, we’ll be well-suited to capture and characterize this melt. But as an expedition leader, early melt raises red flags for the work. We still don’t arrive in Greenland until next week. Scientific campaigns cannot be rescheduled on a week’s notice, so next Tuesday, our FirnCover team will shake hands in Kangerlussuaq regardless. With an April 23rd put-in date, we’re starting early this year. It may still work out just fine yet. Or…

We shall see.

Melt or no, I look forward to the team gathering in Kanger next week. In the meantime, one eye stays glued on the weather data. FirnCover leader, just checking in, for what’s (so far) been an unusual Spring in Greenland.

– Mike

Good luck!