By Jenny Nakai:

Today is a rough day on the seas, with 50 knot winds churning the water and sending the ship bouncing on the waves. In case anyone was wondering, it is not a good idea to shower when the seas are so rough because you might just find yourself bailing out a flooded bathroom, which is even less fun when you are pitching forwards and backwards. My seasickness has returned with a vengeance despite the best efforts of my prescription meds, and perhaps today is a day for lying in the dark with my eyes closed. Anyway, I can describe happier times (i.e. yesterday) in the hopes that my mind can escape the present heaving of the ship.

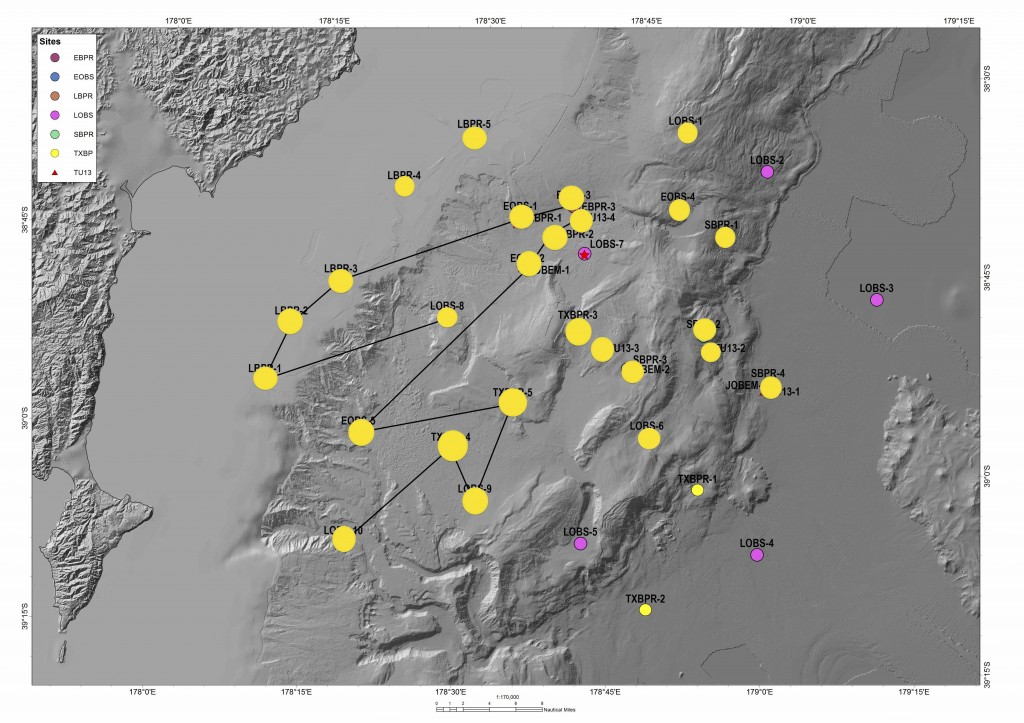

Yesterday was a very busy day. There was an issue with some of the pressure gauges, so we began surveying instruments that have already been deployed. An updated map of completed sites is below.

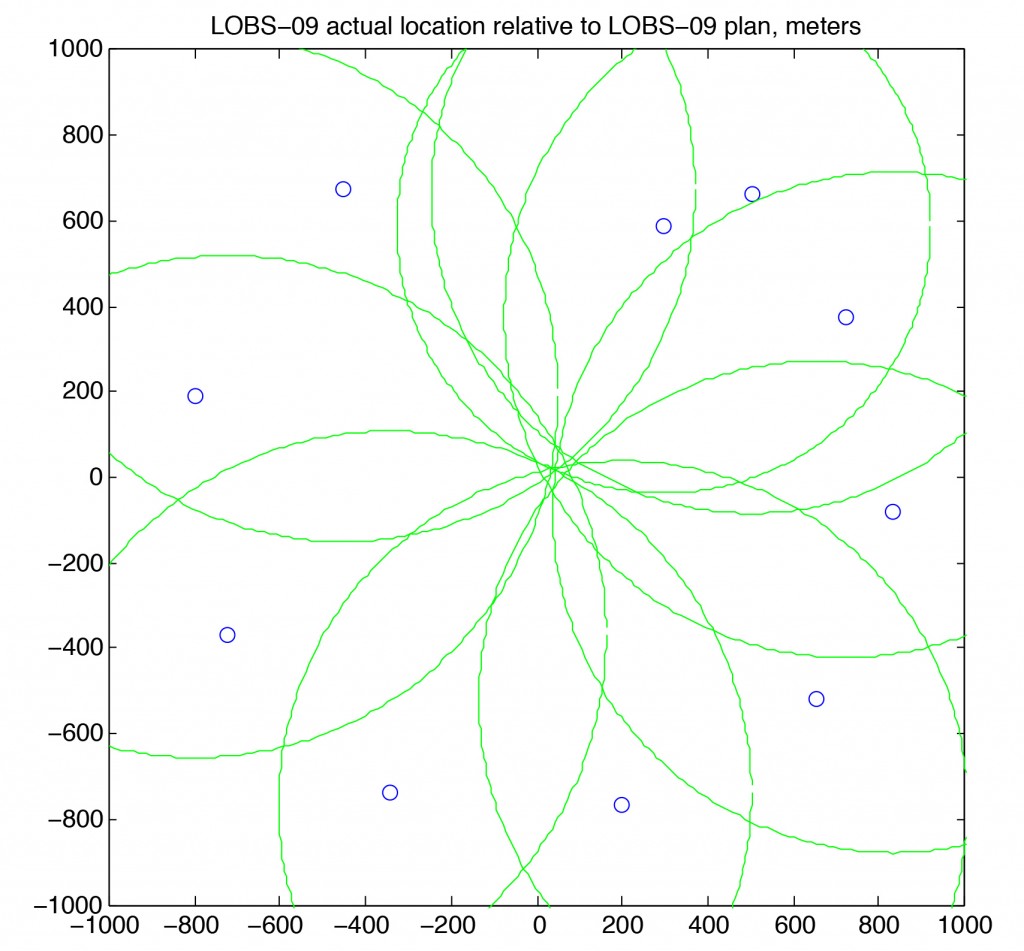

Surveying the instruments is an interesting process, and there are different approaches. One is to complete a circle around the deployed location of the instrument. The deployed location is not always the same as the planned location, at the very least because you cannot get a ship to sit in exactly one spot down to the fifth decimal of latitude and longitude.

As the ship moves in a circle, an acoustic unit sends messages to the instrument; first, an acoustic code to enable the unit to receive messages, which sounds like a series of chirps. If the instrument “hears”, it responds with a series of pings, which sound like beeps. Then the acoustic unit ranges to the instrument, it sends out sound waves that are returned by the instrument, both a direct arrival (to the instrument and back to the ship) and a reflected arrival (to the instrument, bouncing off the water surface, back down to the instrument, and back to the ship). The unit will calculate a distance to the instrument based on an average speed of sound through water based on the first arrival, and voila! A slant distance to the instrument is found. If this slant distance is found for several points around the circle, the true distance of the instrument in latitude and longitude from the deployed location can be found. Spahr was kind enough to lend his code which plots the ranges as circles around the points, which looks very nice and is easy to read. Apparently this is the same transponder used to locate the missing Malay airplane.

The Japanese teams have deployed all of their instruments and will begin receiving data today. When I commented that the Japanese teams have been amazingly efficient, Yoshihiro, from the University of Kyoto, replied, “Yes, yes, that is the Japanese way.” He has done some interesting work in his career and I will write a profile on him in a day or two.

The bottom pressure recorder has a few different components: two yellow cases with floats (glass spheres) inside, the pressure gauge in the large black tube, steel weights (small cylinders near the bottom of the float), and a frame. The bottom pressure recorders are basically acting as vertical component GPS stations, because if they move up, the water pressure is lower, and that will register on the pressure gauge. This works especially well for large displacements, i.e. earthquakes, but you need to know the effect of the tides that regularly lower and raise the pressure on the bottom of the seafloor.

In other news, I finally tried the treadmill a couple of days ago, I set it for a lazy jog at 6 km/hr (3.6 mph), because I was silly and assumed all treadmills are set to miles. You definitely have to pay attention to where your feet are going, one misstep and you may go flying, but it’s manageable. Stay tuned for more interviews once I can move again.

Why are all those instruments needed? Do they measure the same thing in different places, or different things?

Why all the instruments? Well, because they are all sensitive to different things. The pressure gauges are sensitive to a sudden displacement, like that of an earthquake, seismometers are sensitive to all ground motion, both from local earthquakes and far away earthquakes, and the em instruments are meant to measure the conductivity of the plate boundary.