12 April 2020

I always experience a rollercoaster of emotions when I am doing fieldwork. Frustration when things aren’t going well. Boredom waiting for good weather, or just getting to the field site. Loneliness from being away from family and friends. Contentment when you experience the beauty and unique nature of a remote field camp. And, joy when all of your hard work and sacrifice pays off and you are successful in completing the research task you set out to do. Since my last blog post I’ve experienced all of these emotions, and more. These ups and downs can be mentally draining, but the lows make the highs even better.

Since my last blog entry, we’ve been able to do a lot more flights with our DataHawk drones. In the last 8 days we’ve done 15 flights, but these didn’t come easily. We had been riding an emotional high after our first successful DataHawk flights a few weeks ago. But, then a series of storms kept us from flying for the better part of two weeks, with just a couple of flight days in that two week span of time. We spent some of that time working on code to process and plot the data we had collected but we had a lot of down time too. After so many months of waiting to get to the MOSAiC ice camp it was incredibly frustrating to be here and still not be able to fly because of the weather. There are only so many different ways to pass the time on a ship in the middle of the Arctic Ocean before boredom sets in.

Starting last Saturday (4 April) the stretch of stormy, windy weather began to break down. The winds were still a bit stronger than we wanted but we were anxious to begin flying our drones again. Gina and I went out to Droneville, did our preflight checks and had a successful launch.

Caption: Gina and I finish our pre-flight checks as we get ready to do a DataHawk flight (Photo by Delphin Ruché)

As soon as the plane took off and began to climb I could see that it was struggling in the wind, which was blowing at a bit more than 20 mph. As the plane climbed, and the wind speed increased, it was clear that it was too windy to safely operate the plane. Normally, the DataHawks are capable of flying in winds over 30 mph, but it seems that the cold polar conditions are limiting how much power the batteries are providing and reducing the top speed of the planes. Rather than risking the loss of a plane in the strong winds we ended our flight after just 10 minutes. It had felt good to do another flight, but we weren’t all that happy with having to cut this flight short. We’d need to wait for another day to try again.

We returned to Droneville the next day, Sunday, to do more DataHawk flights, but once again, our hopes of easy flying were dashed. Gina was the RC pilot for this flight, while I monitored the plane on the ground station laptop. Gina had a smooth take off but strong winds aloft forced the plane to drift further from us than we would like. When Gina put the plane into autopilot mode it began to return towards us, but it wasn’t quite moving in the direction we had expected. Normally, we want the plane to do spiral ascents and descents close to where we are standing but the plane was moving towards a location several hundred meters away from us. As Gina watched the plane it suddenly began to descend, getting dangerously close to the ice. She switched into manual mode but the plane failed to respond to her attempts to pull up and it crashed. We had to cross a couple of ridges of jumbled ice blocks to reach the plane. When we found it there was no physical damage but none of the electronics – the motor, autopilot or lights were working. It appeared that the plane had an electronics failure in flight and that is why it began to descend and why Gina couldn’t regain control of it in manual mode. It was another frustrating day and we were both feeling pretty low.

The only option we had was to continue pushing forward to do our flights and complete our research. We returned to Droneville on Monday. Our pre-flight checks went well and we had a smooth take off, with me on the RC and Gina running the ground station.

Caption: Gina after a successful DataHawk launch (Photo by Delphin Ruché)

After a few quick turns in manual mode I switched the plane into autopilot. Just like the previous day, the plane appeared to be heading in the wrong direction once it was put into autopilot. The plane quickly moved further away from us than we were comfortable with and appeared to be heading towards the Polarstern. One of our main rules is that we don’t want to fly near anyone or any infrastructure on the ice floe, so I took manual control of the plane to prevent it from getting any closer to the ship. Unfortunately, the plane had flown far enough away from us at this point that it was difficult for me to see its orientation and I quickly lost control of the plane. Once again, our flight ended in a crash landing. Luckily, I did manage to bring the plane down where it didn’t hit anything but snow and the plane survived with only minor damage.

At this point we were at a loss as to why the planes seemed to not be following their pre-programmed flight plan. What was causing the planes to drift so far from where we wanted them to fly? As we thought about this we did some quick calculations to see how far the ice floe was drifting in the time it took us to do our pre-flight checks and launch a plane. We knew that the ice was moving but had assumed that it was moving slow enough to not cause any real problems for our flights, which are linked to the latitude and longitude of the plane when it is first powered up. Our calculation revealed that in the time between when the plane was powered up and when we launched it the ice had drifted about 200 m. And just like that, the mysterious behavior of the DataHawks during our flights over the past two days was solved. The plane was following its pre-programmed flight path, but us and our ice floe was drifting relative to the fixed latitude and longitude of the flight plan, which caused the plane to fly further from us than we had expected. The direction and speed of the ice drift varies from day to day and on this day the drift caused our plane’s flight plan to drift towards the bow of the Polarstern, which is why the plane was heading towards the ship before I took manual control of it.

Despite having another failed flight, we were starting to feel better because we were able to figure out the source of our problem. And, we were able to develop a solution for dealing with it. Now, before take-off we’d verify the position of the plane on the ground control map and from this we could determine how far and in what direction the ice had drifted while we went through our pre-flight checks. We could then reposition our flight plan to match the current location of the plane. During the course of the flight the ice would continue to drift but the RC pilot would now know to watch for this drift and could ask the ground station pilot to continually update the position of the flight plan to compensate for the drift.

As we headed out to Droneville on Tuesday we were cautiously optimistic that we’d have better flights than the previous days. After completing our pre-flight checks, we verified the position of the plane on the ground control laptop and modified our flight plan to account for the ice drift that had already taken place. This flight went perfectly. All of the frustration of the past weeks of stormy weather and unexpected problems with our flights was replaced by relief and happiness that we had just completed a successful flight. We did a second flight later that day and once again it went smoothly. We felt as though we had turned a corner and were ready to start making real progress on our work. Our patience and perseverance seemed to be paying off.

Caption: A DataHawk drone orbiting overhead during one of our successful flights.

Our success flying the DataHawks continued over the next several days and we managed to do 2 to 3 flights per day for the last 5 days. Of course, the flights aren’t the end goal but just a means for us to collect the data we need for our research, and in this respect these days were also a success. We’ve managed to collect data that shows a variety of different atmospheric conditions that will provide lots of avenues for our research when we get back to Colorado.

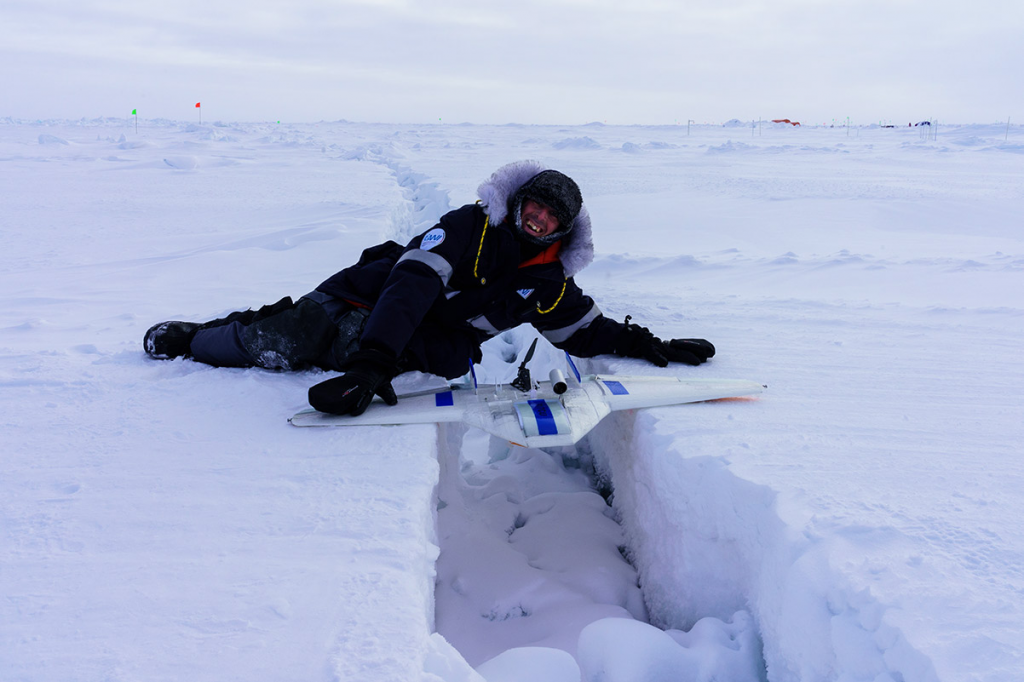

Caption: In the last week several new cracks have opened in the sea ice near Droneville. Here I am posing with a DataHawk over one of these cracks.

As I mentioned at the end of my last blog post we are facing an uncertain timeline as to when we’ll be able to return from this expedition, due to travel restrictions related to the coronavirus. For some of us a long delay is going to present personal and professional difficulties so plans are being developed for a small plane to fly to the Polarstern and transport a few people out of the Arctic. I’m planning to go on that flight, if it happens, but Gina has decided that she’d like to stay on the Polarstern and continue our work until other members of our team arrive. I really appreciate Gina’s willingness to continue our work, but the DataHawk flights require two people – a remote control pilot and a ground control pilot. Serving as the RC pilot requires a lot of practice and training, but operating the ground control software is not as difficult. We’ve begun training two other scientists, Julia and Andi, to serve as Gina’s ground control pilot if I leave. After a short lesson they were ready to start flying with us. Gina and I took turns helping them operate the ground station while the other one of us acted as the RC pilot. At this point, Julia has done several flights with us as the ground control pilot and she has done a great job with this. Andi hasn’t had time to fly with us, but we expect that he’ll also have no problem filling this role. With Julia and Andi’s help Gina will be able to continue our DataHawk flights and research if I leave.

Caption: A group photo of the MOSAiC leg 3 atmosphere team. Andi (1st row), Gina (2nd row) and Julia (3rd row) are in a line in the center of the photo and I am sitting on an ice block on the right side of this photo. (Photo by Christian Rohleder)

I am so thankful for Gina’s willingness to take on this challenge and responsibility and for Julia and Andi’s help. One of the best parts of doing field work is the strong sense of camaraderie that develops. Everyone works together to help each other to ensure that everyone’s projects are as successful as possible.

As I am writing this blog it is Easter Sunday. We are celebrated the holiday with a campfire on the ice last night and a barbecue dinner tonight. Several different groups of people took walks around the ice floe this afternoon to enjoy the nice spring weather here. It was a beautiful sunny day with a dark blue sky and almost no wind. Of course, spring in the Arctic isn’t as warm as it is at home and the temperature for our stroll around the MOSAiC floe was in the -20s F. I guess shorts and T-shirt weather is still a few months away here 🙂

Caption: The Polarstern behind several ridges of jumbled ice blocks near Droneville.

John

I had a couple of questions!

First, how long does it take you guys to do your pre-check before the flight? 200 m seems like quite a ways to move during something that I assume only takes ~15 minutes or so.

Second, is there any crevasse danger up there?

Hi Shelley,

Response from John:

(1) If the ice floe and ship are drifting at 0.1 knots (~.1 mph) then we’d drift 185 m (~600 ft) in 1 hour. On the day I discussed in the blog post we were drifting between 0.2 and 0.4 knots (~0.2 – ~0.4 mph). Normally, our pre-flight check takes 10 to 15 minutes, so we’d drift about 50 m (~165 ft) during our preflight routine if our drift speed was 0.1 knots. On the day I was describing we were training a new ground control pilot and so the pre-flight routine took much longer – about 30 minutes. In that time, with our drift speed that day we did drift about 200 m (~655 ft). When I calculated how far we drifted I was surprised, like you, that we’d go that far in such a short amount of time.

(2) Cracks in the sea ice are absolutely a concern whenever we go onto the ice floe, which is pretty much every day. The ice is very dynamic and new cracks seem to form almost every day. Many of these cracks are small – maybe just a fraction of an inch or a few inches across and pose no threat. Some cracks are bigger – up to several feet across. We have a couple of cracks of this size on the “road” from the ship to Droneville and we do need to be careful when we cross them. Over time, new ice forms in the crack and the risk of falling into the sea is reduced. One danger is if it is windy a thin layer of snow, like a cornice, can form on the edge of the crack and hide its true width. In that case, it would be easy to step on that thin snow and fall into the water. We all carry ice picks that would allow us to climb back onto the ice floe if we fell into the water. In addition, each group carries a throw rope so the people that haven’t fallen into the water can throw it to someone that is in the water and help pull them out. So far, on this leg we’ve avoided having anyone fall all the way into a crack, although a few people have gotten wet feet stepping through thin snow.