The day starts at 4:00 in the morning. I leave the hotel with Sean Waugh, a storm chaser with a PhD in meteorology, in his truck rigged with a suite of instruments supporting boundary layer observations, which he built himself. We arrive at the leach airport and start setting up for the first weather balloon launch of the day. Launches are scheduled for 6:00, 9:00, 12:00, and 15:00, although we release the balloon half an hour before schedule so that it reaches a select part of the atmosphere and can send useful data sooner.

Mobile Mesonet Truck with rack of layer boundary observation instruments

There are a few droplets of precipitation in the morning, making it a little cool. However, this morning was warmer than yesterday morning, possibly due to held in radiation from overnight clouds. Matt Wilson, a meteorology student working on his master’s at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln (UNL), calibrated the measurement device (known as a radiosonde) on a radiosonde cradle station. The small station hooks up to the radiosonde to calibrate its sensors and also heats them in order to ‘burn off’ any impurities that may create uncertainty. Once this is done, taking about 3 minutes, Matt takes the radiosonde a few feet from the truck so that it can emit radio frequency free from noise and get picked up by the truck’s antenna. Meanwhile, I inflate the balloon with something around 1.5 kg (a little more than 3 pounds) of helium. Windy conditions and precipitation require more gas in order to provide sufficient lift for the balloon. After this, the radiosonde, which is tied to a 30 meter (100 foot) string to keep the measurements free of influence from the helium balloon, is attached to the balloon with zip ties. From here, Sean holding both instrument and device wait for the sign that data is being sent. Once it’s 5:30, he releases both and waits.

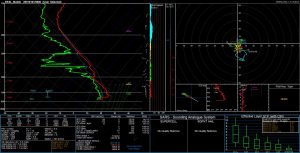

As the data comes through, in real time, we gather around the computer processing soundings. It displays a graph of the humidity, temperature, and pressure plotted against a height series. This helps give us a measure of the different properties at different vertical layers of the air. The radiosonde also has a GPS. Usually, these simple large helium balloons are capable reaching upwards of 20 kilometers (almost 12 and a half miles!) from sea level into the atmosphere. As the balloon passes the 5.5-6 km (3.5 mi) mark, a specific change in humidity is observed. This is because the San Luis Valley is holding down moisture below a certain point in the air. Another notable measurement, occurring yesterday afternoon, were the observations made as the weather balloon passed through the cloud layer that developed in the afternoon. Shown below is an image presenting the boundary layer where humidity drops, this is represented through the dew point (green line).

Radiosonde sounding product. Green line shows dew point, red line shows temperature.

(Feature Image Credit: Matthew Wilson, Master’s Student at UNL)