The reality of field work is sometimes an ugly one. In an ideal world, you show up to your site, the weather’s good, your instruments and tools work, and you get a fantastic dataset. That, through preparation of your team and your equipment (and usually by a little bit of luck on the weather side) is what you hope for, but you do your best to plan for anything else that may come up. For this campaign, we prepared our equipment as had been done for previous successful campaigns, made sure that we had more than enough stuff with us, shipped everything a few days earlier than required, and even (so far) got lucky with good weather. But as I alluded to in the previous post, getting the aircraft flying as they should has been challenging, and Dale, Nathan, Will and I have spent the last three days troubleshooting, fixing, and learning about the situation — in the process we’ve launched and recovered 53 airplanes!

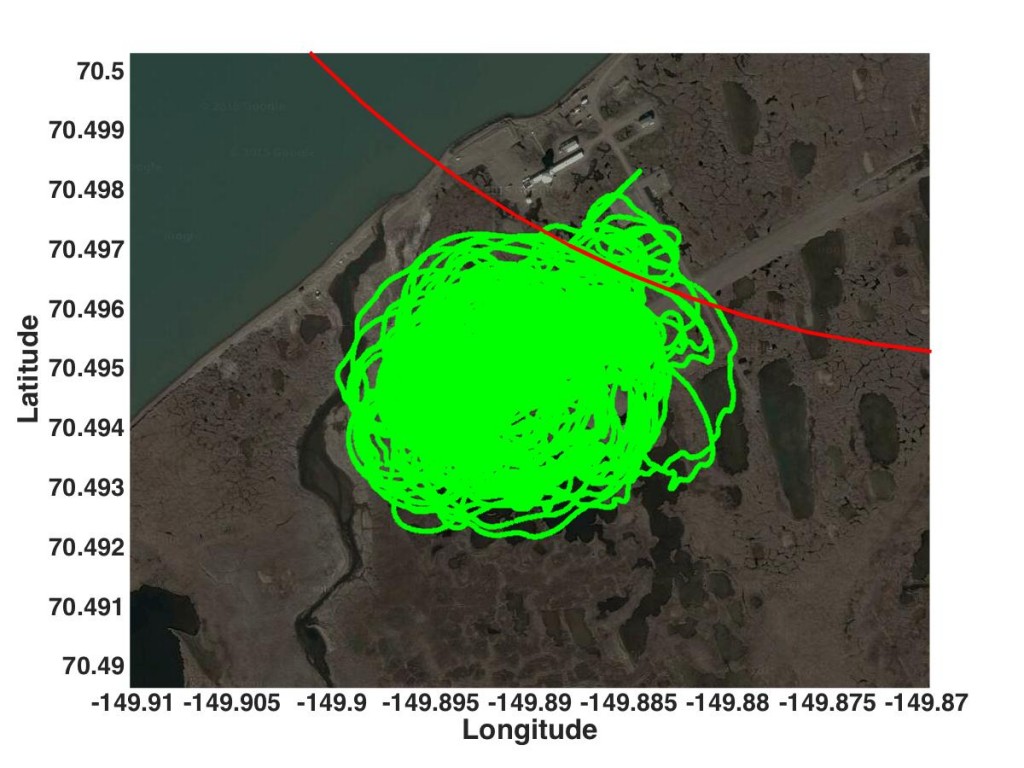

A map showing all of the flights (53 (!) in total) completed over the last three days in order to try to troubleshoot the aircraft issues we have been having.

At this point, it has become increasingly likely that what we are being impacted by something beyond our control. As crazy as it sounds, with a bunch of testing, it is becoming more and more likely that the cause behind all of our troubles is interference from the USAF radar facility. What makes this all the more challenging is that we know very little about this radar (we asked for details but were told we don’t have the correct clearances to obtain that information), and we can’t turn it off to test to see whether our theory is true (we know better than to ask them to turn it off for a while!). Fortunately, we’ve been able to gain a small amount of knowledge through the internet (thanks Wikipedia!). In the end, what this means for us is that nearly every time our aircraft is flying somewhere between 30 and 100 meters for any extended period of time, our autopilot is being impacted to the point where it nearly cripples the plane. This was confirmed yesterday afternoon through a series of test flights where we used a remote control handset to hand fly the plane at a series of altitudes. The frequency with which our autopilot was impacted upon reaching ~50 meters was astonishing.

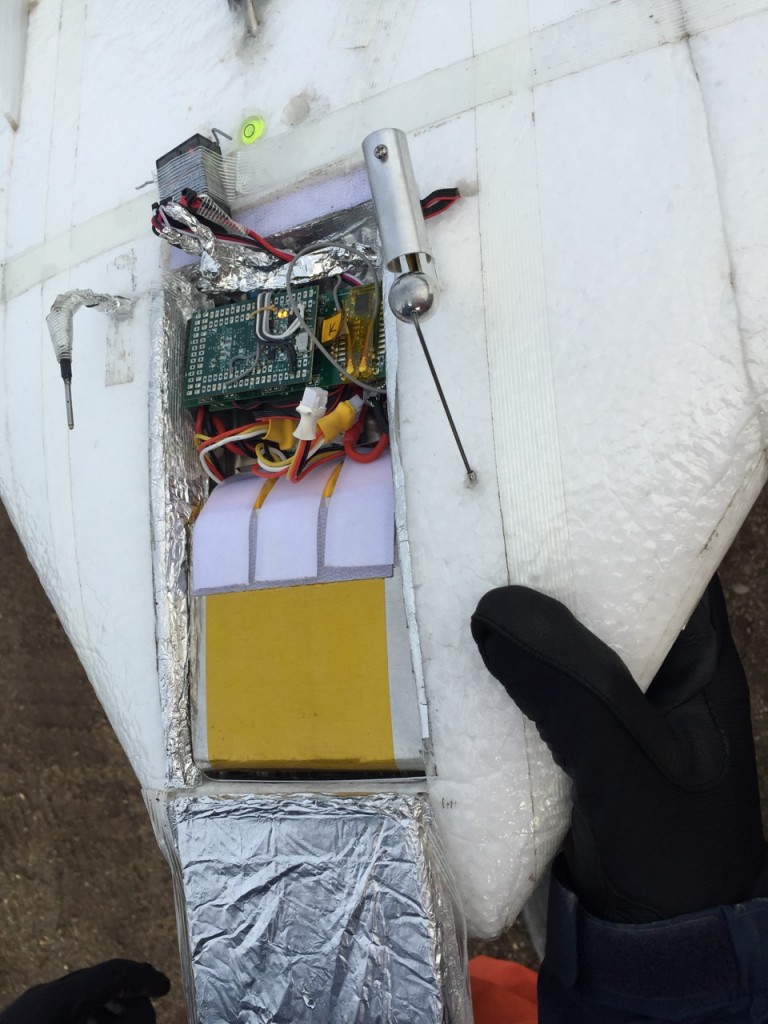

The DataHawk being launched in front of the radar facility that appears to be giving us a whole load of trouble.

So how do we fix it? Well, we’re still working on this, but the first idea was to shield the sensitive equipment from the radar’s impact and change our flight plans to avoid this area of elevated exposure. The second part can be done easily, but will not guarantee success since the airplane will still need to pass through the 100 meter altitude in order to get above the radar beam. The shielding is substantially tougher, and we decided that our best chance was to wrap the payload bay with aluminum foil. We did so after dinner, performed some initial test flights and were disappointed to find that this did not seem to help at all. Next, Dale dissected the aircraft a bit further in order to add extra shielding to pretty much anything that could take it, but this again did not solve things. The nice thing about the extended daylight hours up here is that you could essentially troubleshoot things and continue test flying throughout the night, if necessary. However, the unfortunate thing about those extended daylight hours is that you never have a natural stopping point and there is extreme temptation to continue working on things until you’ve got them figured out. The body can only take so much of that before fatigue becomes a real issue, and by the end of last night I could tell that the team is getting tired from the long days up here without the beneficial lift that flying successful missions brings with it.

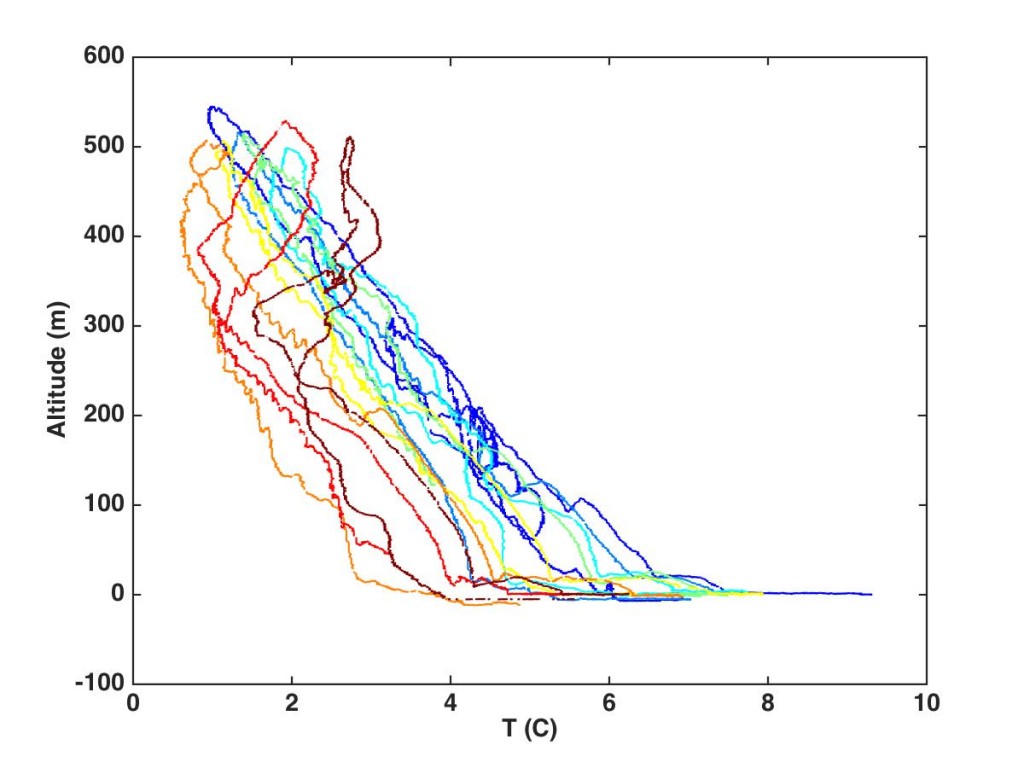

This morning, we spent a bit more time troubleshooting and found that while not 100% repeatable, what we had experienced the day before was again happening frequently. Without additional avenues to pursue, at lunch time we decided that it was time to begin going after some atmospheric measurements (what we came here to do in the first place!!). To do so, we kept our flights to manual mode only, and had Will and Nathan perform hand-flown profiles through the lower Arctic atmosphere. By applying maximum climb rate to get through the “danger zone”, we were able to, for the most part, get the plane to an altitude where it seems to be out of reach of the radar. This has allowed us to capture hourly profiles of the lowest 500 m of the atmosphere between around 11 am and 9 pm today. I can’t tell you how good it feels to begin collecting measurements — we’ll do more of this tomorrow while simultaneously trying to continue troubleshooting the radar interference.

Temperature profiles from the surface to 500 m above the surface from 6 August. These were collected roughly once per hour, with the earliest profiles (starting around 11 am) in blue, and the latest profiles in red.

Loving the Blog Gijs! Field work is a challenge but it is so important. And those radars are a pain! All the best!

Thanks Scott! Yes — I think right now our best strategy is to dodge the beam. Seems to be working somewhat predictably.