Lake Vanda, Wright Valley, Antarctica

January 14, 2017

I arrived at the Lake Vanda field camp on Tuesday January 10th, where I’ll spend about 10 days flying unmanned aircraft (drones) to make atmospheric measurements. Lake Vanda camp is about 70 miles northwest of Scott Base. To get to the field camp me and two other scientists flew on a helicopter from Scott Base. This flight took us over Hut Point Peninsula, on the southern tip of Ross Island, across McMurdo Sound, which was still completely covered in sea ice, and finally into the valleys of the Transantarctic Mountains. Helicopter flights are always one of the highlights of an Antarctic trip since they provide a fantastic aerial view of the stunning Antarctic landscape.

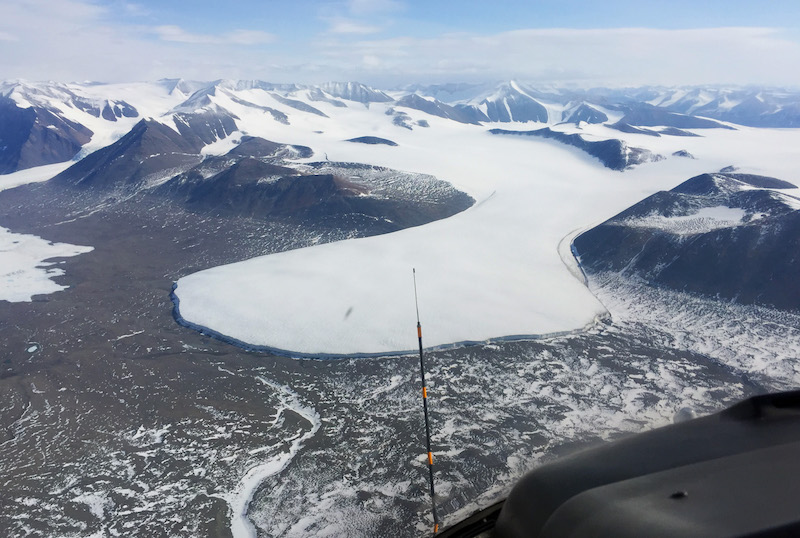

On all of my previous Antarctic trips I have never had the opportunity to visit the McMurdo Dry Valleys (MDVs). As I mentioned in my first blog post of this trip one of the things I was really looking forward to on this trip to Antarctica was getting to visit the MDVs – an area of spectacular ice free valleys cutting across the Transantarctic Mountains. As we flew towards the Lake Vanda camp I got my first glimpse of the MDVs and I was not disappointed. Just beyond the mouth of Taylor Valley we flew over Commonwealth Glacier draining into the ice free expanse of the broad valley.

We then flew over the rocky, glacier covered spine of the Asgard Range before crossing into the Wright Valley, where the Lake Vanda camp is located.

View from the helicopter as we flew into the Wright Valley. Several glacier tongues are flowing off of the Asgard Range (on the left side of the image) into Wright Valley. The ice covered area in the far distance in the center of the image is Lake Vanda covered in ice.

Wright Valley is 1 to 2 miles wide and about 20 miles long. The valley was carved by glaciers in the past and has the classic U-shaped cross-section of glacial valleys – with a broad, nearly flat valley bottom and valley walls that become nearly vertical as they rise to the adjacent ridges. The ridges that bound Wright Valley (the Asgard Range to the south and Olympus Range to the north) rise over 3000 feet above the valley floor.

The camp consists of three small green huts, connected into a single structure, and several tents.

One hut serves as the camp kitchen and the other two huts are used to prepare our science equipment and to provide a comfortable place to sit as we analyze the data we are collecting. Power is provided by a single gas generator, which we usually keep running during the day but turn off at night. Cooking is done on two gas camping stoves similar to what you would use if you were car camping. Most of the food is canned or dry food although we did also bring some frozen vegetables and meats. Breakfast typically consists of cereal or oatmeal and tea, coffee, or hot chocolate. Lunch has been a variety of quick meals. Dinner is usually the biggest meal of the day with a rice or pasta dish with vegetables and a meat dish.

There have been between 7 and 12 people at camp since I arrived on Tuesday. Everyone at the camp is working on the same science project focused on the environment of the MDVs. Because the huts are small it gets pretty crowded in camp, especially at dinnertime when everyone is in the kitchen hut.

The tents are rugged polar mountaineering tents designed to withstand the strong winds that often occur in Antarctica. The tents have enough space for two people and their personal items, although I’ve been lucky enough to have a tent to myself giving me a bit of personal space when I want to get away from the crowded huts.

Our sleep kits include a thick insulated inflatable sleep pad like you’d use when backpacking and two sleeping bags. At colder camps one sleeping bag would be put inside the other sleeping bag to provide a very warm place to sleep. Our camp is not at a high elevation (just 300 feet) and since it is the middle of the Antarctic summer it isn’t too cold with temperatures hovering around 30 F. In my tent, I’ve placed my extra sleeping bag on top of the inflatable sleep pad to provide a bit more padding on top of the rocky ground. The temperature in the tent can get quite warm when the sun is out, warming to 50 or more degrees F, but becomes chilly when it is cloudy with a temperature closer to 40 F.

As you might expect the bathroom facilities are pretty limited at a remote field camp like Vanda camp. Our “bathroom” is a few hundred feet away from camp behind a boulder and consists of a plastic bag lined bucket. We also keep pee bottles in our tents so we don’t need to get dressed for middle of the night visits to the bathroom. We don’t have any running water in camp so we can’t shower or shave. Fortunately, with the cool weather we don’t get too sweaty and there isn’t as big a need to shower every day as there is at home. Still, I’m looking forward to my first shower when I get back to Scott Base.

The weather has been relatively pleasant since I arrived in camp with temperatures mainly in the 30s F. The wind has been light in the mornings but increases to 20 to 30 mph in the afternoon. We’ve had a mix of cloudy and sunny days and new snow has fallen on the highest ridges around camp on a few days.

We’ve been doing a lot of unmanned aircraft flights but I’ve also had time to do a bit of hiking around camp. I’ll describe that and some of the interesting sights here in my next blog post.

John!

This is so exciting! Thank you for including me.

John,

I would like to know about the analysis of the data you are collecting and any conclusions you have arrived at!

thanks Jeff Witman

We’ve only done a preliminary analysis of the data in the field so far – basically just verifying that the data makes sense. The analysis will take quite a bit longer and as that we also need to access archived weather forecast data and will likely run some new weather forecast model simulations.